Was I Wrong on Harriet Miers?

Rethinking what qualities we should be looking for in Supreme Court Justices.

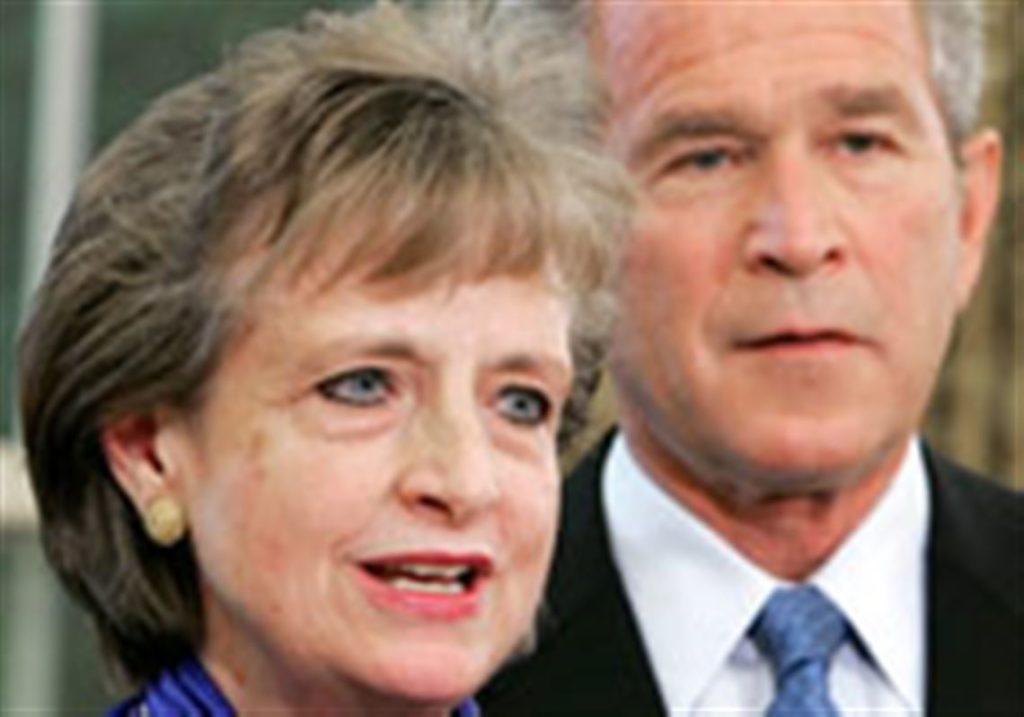

Fifteen years ago, President George W. Bush nominated White House Counsel Harriet Miers to the United States Supreme Court. She was almost universally derided as a mediocrity, unworthy of the nomination, and ultimately withdrew from consideration. The OTB gang, myself included, joined in with dozens of posts. But maybe we were wrong.

I concluded my initial posting reacting to the nomination,

. . . Article III judges are supposed to have an independent perspective. I prefer a judge who will read and apply the Constitution, not factor in their career experience.

In a posing the next day, titled “Harriet Miers: Not So Mediocre?” I laid out my counter to the handful of conservative legal bloggers defending her, notably Miers’ fellow Texas attorney Bill Dyer,* aka “Beldar.”

[Beldar] refutes the “not qualified” label that most have bestowed on Miers. I agree with his reasoning and, indeed, remarked that “her resume is impressive enough” in my initial posting on the subject. Miers is a perfectly competent lawyer who has been quite successful throughout her career, despite having spent the formative part of it in an era when women simply did not become prominent attorneys, least of all in Texas. And she did that long before George W. Bush was in any position to help her.

Still, the former academician in me does expect a Supreme Court nominee to have a “well-considered ‘judicial philosophy'” a’la Randy Barnett. Perhaps that is a luxury of those who live in an ivory tower but it is the most effective way to guage what type of Justice the appointee will make. This is especially important for someone without a substantial tenure as an appelate judge. Pragmatism is likely a good and necessary trait in a litigator. It is likely a recipe for inconsistency as a judge.

Beldar notes that Miers’ resume compares quite favorably with Sandra Day O’Connor and Justice Lewis F. Powell, Jr. at the time of their nominations. To which conservative critics will say: Exactly. Both are bright, decent, hard-working citizens who served their nation honorably. Neither, however, had a consistent view of the Constitution.

To return to now-Chief Justice John Roberts’ sports analogy, judges are umpires. I prefer one whose strike zone is the same from inning to inning and game to game. Ideally, I prefer one whose strike zone is the same as that in the Official Rules of Baseball. If I’m going select an umpire for the World Series who has never called a game before, I would at least like to know what their view of the strike zone is. If they tell me they’ve never thought about it much because they’ve been too busy working, I am unlikely to be impressed.

My views on Miers haven’t changed nor, fundamentally, have my views on the role of the Supreme Court. If nine individuals are going to decide what the Constitution means on an ongoing basis, I want the nine brightest legal minds that we can find.

Further, I still agree with what I wrote fifteen years ago in that closing paragraph. Consistency is perhaps the most important trait for umpires, both literal and figurative. A strike zone or a Constitution that changes willy-nilly is bad for the game or the country.

Still, the bitterness over the election-year vacancies caused by the deaths of octogenarian giants unable to outlast an opposite-party president and the increasing sense of the Supreme Court as a partisan institution have me rethinking the value of both wide real-life experience and relative unpredictability.

Antonin Scalia and Ruth Bader Ginsburg are arguably the two most brilliant Justices of my lifetime and they had well-considered, internally-consistent judicial philosophies. Despite being ideological opposites, they were fast friends. And, instinctually, they remain my archetype of what we should aspire to in selecting Justices.

Yet maybe we’d be better off with more Sandra Day O’Connors, Lewis Powells, and Anthony Kennedys. They were all swing justices who vexed their Republican cohorts for being inconsistent and mushy. But the upside was that they were seldom seen as partisan or team players but rather honorable folks carefully weighing the consequences of their votes.

Neither O’Connor nor Powell would be considered for the Supreme Court today. The former was a top graduate of Stanford Law (finishing third in a class where future Chief Justice William Rehnquist was first) but spent her career in state politics, first in the Arizona Senate and then on the Superior Court and Court of Appeals. Powell spent several years in the military, then a stint in private practice, and many years in Virginia politics before his selection.

Kennedy, who replaced Powell, had a more traditional path to the Supreme Court, spending a dozen years on a US Court of Appeals before his nomination. Still, he spent several years in private practice and as a law professor at a relatively mediocre institution. Nowadays, the path dependency is such that one’s chances of becoming a Justice all but evaporate if one fails to obtain a Supreme Court clerkship at 25.

Again, I’m still an intellectual at heart and, indeed, much more steeped in it professionally than I was in 2005. I still admire the sterling credentials and achievements of a Scalia, Ginsburg, or John Roberts or even an Amy Comey Barrett. But the reverse side of that coin is Brett Kavanaugh: a self-entitled jerk who has never had a moment of self-reflection because he’s hit all the right wickets at the right times and believes he’s damned well earned everything he has.

Maybe we were better when we had the likes of Earl Warren as Chief Justice. Not so much ideologically but, indeed, precisely because of the ideological unpredictability. A lifelong Republican appointed by Dwight Eisenhower (who very much rued the choice) he presided over perhaps the most liberal court in American history. But his experience before his appointment was rather stellar: Berkeley Law, local prosecutor, state attorney general, governor, and failed candidate for both Vice-President and President. And he brought a politician’s knack for negotiation, managing to wrangle unanimous decisions on most of his Court’s most controversial cases.

Granted, Warren’s tenure was incredibly controversial and, indeed, may have been a genesis of the modern notion that the Court was the epicenter of social policy and the thorough vetting of potential nominees to game the system. But there’s something to be said for having at least some Justices who have legislated and governed overseeing those who write and execute the laws rather than leaving the task entirely to brilliant theorists.

_____________________

*Does anyone know Bill’s whereabouts? He stopped commenting at OTB as much after the Miers flap but never forgave my insistence that Sarah Palin was an ignoramus unfit to be Vice-President. He stopped blogging suddenly in 2017 and his personal legal page is also down.

There’s no way to design a “perfect Court,” but personally, I like a mix. Yes, having Greats like Scalia and Ginsburg is important. I think their intellects and strong foundations forced the rest of the Court to examine issues through varied lenses.

Having moderates on the Court serves an important function too. “Moderate” doesn’t mean “intellectually weak,” at least not to me.

This is why I am so incensed over McConnell’s maneuver re: Garland. The pattern of when the President’s party holds the Senate you get the Justices you want, vs. when the opposite party holds the Senate you get the Justices you need, isn’t a bad thing.

The Bad Thing is an ideologically lopsided Court that has the potential to think that they are in a position to “right wrongs,” and upend precedents that will change people’s lives, not necessarily for the better (and in fact demonstrably for the worse in many cases).

@Jen:

While I’m not quite incensed about the gambit, that had long been my understanding as to the unofficial deal in place. And Obama upheld his end of it in nominating a slightly long-in-the-tooth moderate.

Oh my…break out the smelling salts and the fainting couches…

My bar association cocktail party conversation starter for years has been my hot take that Harriet Miers got screwed (and by way of context I am a left-of-center Democrat).

Miers had an extraordinarily wide-ranging resume, including running for and being elected to Dallas city council, working for a plaintiff’s firm, working for (and becoming managing partner of) a top tier corporate defense firm, being president of her state bar, running a state agency, and working at the White House. The current crop of SCt Justices have nothing like that range of experience: I think Sotomayor is the only one who’s ever tried a case or conducted a jury trial as a trial judge.

If Miers is obviously unqualified for the Supreme Court then there is something badly wrong with the criteria. I suppose one could argue that a Supreme Court of 9 Miers might not be desirable, but 9 Scalias would be much worse.

Chuck Klosterman once drew a distinction between “who is the top QB in the world” and “what is the best rock and roll band in the world.” The first question has a handful of conceivable answers. The second question could plausibly be answered with “these guys who are currently working at a car wash in Detroit.” We have let the SCt selection process drift way too far to the first type of inquiry: one ought to be able to come up with a list of 500 names, not 5.

@James Joyner: The ideal situation is one where both parties act in good faith. In such an environment the blue slips, the filibuster and the recognition that what goes around comes around act as a check on putting someone radical or corrupt on the court. I hope that someday we can get back to that semi-formal system.

I’m trying to remember – Why was she nominated in the first place? Was there any suggestion that there was corrupt or nepotistic reasons?

@An Interested Party: Orrin Hatch:

This is a fine example of the pot calling the kettle black. Politicization of the court is the point of the latests maneuvers – installing judges who are believed to be “reliable” in certain areas of policy. It’s why Garland wasn’t given a hearing or a vote.

What did you have to say about the Garland nomination, Senator Hatch? Well, before the election he said this,

There was also this:

Hmm, sounds like theater to me. But this is normal in politics. I give him a pass. However, it means I don’t quite give A+ credibility to what he says.

Here’s another quote I found on Ballotopedia:

As if Obama was responsible for Scalia dying?

Well, I would be much happier with Harriet Myers than Brett Kavanaugh, that’s for sure. So far, his writing hasn’t impressed me at all. He seems every bit the partisan hack I thought he was.

I remember at the time that I thought this was a very smart move by Harry Reid, who I recall suggested the pick to W. Because of the (what I think of as ridiculous) credentialism of the Senate and the zeitgeist, I knew she would be unpopular. Heck, she probably didn’t have the seal of approval from the Federalist Society – because who has time for that nonsense?

I think you are overestimating the consistency of Scalia’s legal analysis, but let’s skip that…

Having worked with lots of the brightest minds in my field, I can only say “oh, god, no.” The brightest can create elaborate structures of logic and supposition to support whatever it is they wanted to do in the first place, and they will pat themselves on the back while doing so. And I don’t see any evidence that the brightest minds in law are any different that way.

The most important quality in a judge is the oft-derided empathy. Quite simply, all the important cases before the court occur when rights come into conflict. We need people who understand this, and who realize that they are balancing rights that have real world consequences.

Anti-discrimination laws are the easiest example — they violate the bigot’s right to freedom of association, which is why you have some libertarians that believe that they are all unconstitutional. At the same time, the laws strengthen the rights of the oppressed.

Coming up to the Court will be a lot of Religious Freedom vs. LGBTetc Rights cases, and they are the same issue — balancing rights.

I’d rather have 9 mildly dim people who take the consequences of their decisions into account, rather than 9 brilliant people who believe that they can divine the one true meaning from a document written 250 years ago by slave holders, with massive revisions after the civil war. That document is a lot of things, but it is not a precise guidebook.

My only relevan counterfactual question is: would Miers have been preferable to Scalito*?

*Not a typo.

I find this whole Supreme Court discussion frustrating. What has become increasingly clear in the last decade or so is that the Supreme Court justices are nowhere near ivory tower intellectuals who rationally come to their decisions using cold, implacable logic.

No, it is they come with ideological bias who reverse engineer their opinions into rulings that justify their opinions.

The public fiction we tell ourselves has completely been unraveled by the fact that the last 3 justices were pre-selected and vetted by an ideological organization geared to rule in specific, ideological ways. The very legitimacy of the Supreme Court is now under question. It does not bode well.

@MarkedMan:

Honestly, I think it was because Bush worked with her for years and liked, trusted, and respected her.

@alkali:

That’s my understanding as well and is honestly as big a problem as partisanship. The lack of trial experience, and also often criminal legal system experience (both prosecution and *gasp* defense) shows up in a lot of really bad decisions (or an instinctive tendency to giver overwhelming deference to the State’s side) in matters relating to Criminal Law.

@Jen:

Did Scalia ever write an opinion or dissent that did not end up arguing for his personal preference, regardless of the Constitution or established law? Certainly not an important one. That kind of brilliance in service to prejudice is exactly the kind of justice we do NOT need.

As I recall, the basic rip on Miers is that W. didn’t look past his own office to find a candidate and that her only credential was sitting in W.’s sight line. I regret that her varied career wasn’t really weighed in her favor and I don’t think it serves the Court well when all the justices have similar resumes. Being an appellate judge is good training, but I think having a mixed team (in all senses of that word), each of whom has a sound legal education would make a better court. Let the former appellate judges bring their skills to the table, but also the former litigators, former trial judges and former politicians because they have different strengths, all of which would benefit the overall court.

As one small example, I started my career as a law clerk in a federal district (trial) court. It was pretty common for us to come across Supreme Court opinions that were basically unworkable at the trial level or would create outcomes that were clearly contrary to the intentions of the opinion writers.

As I recall, the basic rip on Miers was that W. didn’t look past his own office to find a candidate and that her only credential was sitting in W.’s sight line. I regret that her varied career wasn’t really weighed in her favor and I don’t think it serves the Court well when all the justices have similar resumes. Being an appellate judge is good training, but I think having a mixed team (in all senses of that word), each of whom has a sound legal education would make a better court. Let the former appellate judges bring their skills to the table, but also the former litigators, former trial judges and former politicians because they have different strengths, all of which would benefit the overall court.

As one small example, I started my career as a law clerk in a federal district (trial) court. It was pretty common for us to come across Supreme Court opinions that were basically unworkable at the trial level or would create outcomes that were clearly contrary to the intentions of the opinion writers.

@Jay L Gischer:

You beat me to that point. Since Souter, there has been a great over emphasis on ticking off boxes, Top law school, though in reality only Harvard, Yale and sometimes Princeton, clerking for the right sitting SC justice and appeal court experience. Plus they must be young.

The country would be better served if a former governor or senator was on the court and a former trial judge.

Yes, Warren disappointed Eisenhower, and Byron White would have disappointed Pres. Kennedy.

If your only tool is a hammer… If you’ve spent your career as a law professor arguing over fine points of legal interpretation you’re prone to seeing every problem as one of fine points of legal interpretation,

@DrDaveT:

That’s basically why I stopped reading George Will decades ago. The most basic of partisan hacks wrapping it all up in brilliant-sounding rationalizations. No consistency, no ethics, no morals.

@James Joyner: Oh yeah, now I’m remembering. I came away with the impression that her biggest flaw was that Bush ignored the “advise” part of “advise and consent” and he needed to be reminded that consent was not a given.

That was in the old days when Republican members of the Judiciary committee had interests other than pure partisanship.

@An Interested Party: what a load of hysteria. (And what a shitty site national review is now. I had to close three pop-ups)

@DrDaveT: I doubt that I can find many (if any) cases on which I would agree with Scalia, and admit that I am deferring to the opinion of RBG on his alleged brilliance. She saw something in him that I cannot, but I respect HER enough to believe it was true.

I wholeheartedly agree.

I just pulled one of my Con History books, and ended up mad at Scalia all over again, this time for his vote in Edwards v. Aguillard. I am not a fan.

@Scott: @DrDaveT: @Jen: Jeffrey Rosen’s “What Made Antonin Scalia Great” is a a fair-minded discussion of the matter. No Justice is perfectly consistent but he at least tried to be and he did indeed on many, many occasions rule against his own policy preferences and those of his fellow conservatives. And I like this line:

@Jen:

They both like opera.

@Gustopher: I was going to write it but you already did. I really don’t want 9 legal Albert Einsteins. I’d much rather have nine pretty smart people with good values.

Anyway, smart people can be nuts too.

“Smart people believe weird things because they are skilled at defending beliefs they arrived at for non-smart reasons.”

-Michael Shermer

@Scott:

One of the opinions from the last several years that I read in close detail (IANAL) was Massachusetts v. EPA where the Court ruled that not only could greenhouse gases be regulated under the Clean Air Act, but that they must be regulated. Then went into extraordinary gyrations in the opinion, concurrences, and dissents to present conflicting definitions of what the word “anyway” meant, since it was critical to the decision.

@Teve: If the Democrats win the White House and the Senate next week, be prepared to see a lot of screeds like that telling us how the world will come to an end if Democrats dare to play hardball like Republicans…

@MarkedMan:

I used to watch all the Sunday shows and quit about 20 years ago for a number of reasons. One of the very last episodes of This

Week I saw, George Will gave some very elaborate, linguistically ornate explanation of how nothing FDR or the New Deal did had anything to do with recovering from the great depression, the recovery happened solely due to the massive expenditures of WW2. Not a second after he finished Paul Krugman turned it to the host and said “Mark this day on the calendar, the day that George Will admitted that massive government spending can solve a recession!” And for the rest of the segment Will just sat there fuming with a scowl on his face. I was not surprised a few years later to see him promoting Amity Shlaes, another complete fraud.

@Jen: having followed creationism for 20 years, I can attest to the shittiness of Scalia’s dissent. Pretending that Louisiana’s insistence of teaching biblical creationism in science class was religiously neutral and purely motivated by a desire for a well-rounded education? Sell that fucking bullshit to the tourists.

This is the age old question posed by a particularly wise Sophist: “Does the Law serve Man–or Man the Law?”

If you decide the latter–then the current profile of a SCOTUS appointees makes sense. If you decide the former–almost none of them makes sense.

The ‘Law” is a tool invented to serve humanity–while it is important to have pure academics that treat it as a thing unto itself (which BTW is how we advance our conceptualizations of Law)–it is probably more important to have people on your Court that understand how the law will impact society and human to 2nd&3rd orders of effect.

Legal philosophies are not bad–but each factor of your philosophy SHOULD be weighted differently for each question before the court. If we are in the construction business–machines and tools become more or less important depending on the thing being built and where its being built.

A predictable vote on the court means the Justice applies the same philosophy and the same weight to ever question–where is the “intelligence” in that? That would imply that same-ness and equality are identical things–a clearly unintelligent conclusion.

@Scott:

I recently read a novel whose underlying theme was a conspiracy to kill all the members of SCOTUS so that the current president could (with a willing Senate majority) appoint only judges of his political ideology. (The protagonist and his associates were all terminally ill and were perfectly happy with suicide by cop).

As fantastical as that sounds, it tends to illustrate the procedural flaw in any effort to provide justice without regard to political bias.

I can’t imagine that the founders intended that the Supreme court should, like a pendulum, swing to and fro on the rise and fall of political fortunes. The adjudication of a case ought to be independent of the appointing president.

Some imagination may be in order to prevent the court from becoming a political “enforcer”.

Simply adding, or reducing, the number of justices is insufficient

As a complete outsider to the law profession but one who does read a lot about the judiciary and legal opinions (for fun even), I don’t think the present system produces that result.

Like many areas of public and social life today, the judiciary is overly reliant on credentials and checking wickets as a bad proxy for judging merit and intelligence. The result closed off all but a few quite narrow paths to the higher-level positions, especially the Supreme Court. One cannot be stupid and successfully navigate the system to get those credentials and wicket-checks, but it’s not a sign of brilliance either, nor is it the only source.

@mattbernius: Alito served for a time as an assistant U.S. Attorney so he had some trial experience albeit on the prosecution side of the table.

@Andy:

Didn’t one of our resident lawyers comment a few weeks ago that the Federalist Society provided a career path for mediocrities?

From a review of the Richard Posner book How Judges Think

@a country lawyer:

Thank you for the correction!

@Joe:

My wife is a federal clerk and had encountered the same issue. Though I should also mention that extends to a number of circuit court decisions as well (at least in the 2nd circuit).

I recall a science podcast a few years back, where the host told about a brilliant physicist, I think Fred Hoyle*, who’d come up with positions against the general consensus (like steady state instead of expanding universe), which were usually wrong. but he argued them in such a brilliant way, that other physicists had to work really hard to prove him wrong.

That might be a good thing in physics, but it would be a rather terrible thing in the Supreme Court. In physics one can prove any argument or theory wrong (though it may take a while and a lot of work); indeed, that’s most of what science is about: testing hypotheses and predictions made in theories.

But once a Court decision is reached, that’s THE LAW, even if it’s dead wrong (see Dred Scott Decision for starters), or even if it hurts large numbers of people (see Dred Scott for starters).

*It might have been Roger Penrose.

I’ve always cringed at the “balls and strikes” metaphor. Balls and strikes are very simple things, they do not require 100 page opinions from multiple courts ultimately needing a final opinion years in the making. Common sense must be allowed into the conversation at some level of law lest the law become an ass.

Dred Scott: Indisputably Dred was private property. Taney calls a strike!

https://thumbs.gfycat.com/IdealisticClumsyConch-small.gif

@James Joyner:

I see this said a lot, but I didn’t see it play out much in Scalia’s opinions. He gets a lot of credit for writing some good criminal procedure opinions, but very few of those actually put him at odds with his stated policy preferences. No doubt there were cases where he held for the prosecution despite the fact that he would have been happy to see the defendant remain in prison, but that was more a matter of accepting collateral damage than ruling against his larger policy preference. Scalia was a strategic thinker who fought with the long term goal in mind.

I started out as a fan of originalism, so I became a fan of Scalia.* I admired his constitutional philosophy and I loved the scathing pen he displayed in his opinions. I’ve tried to read all Supreme Court opinions as they were handed down during the 35+ years I’ve practiced law, and I made it a point to be sure to read every opinion Scalia wrote. Reading him over the years eventually broke me of my love of him. I quit being a fan of originalism in large part because of the way I saw Scalia twist the tools of that method to reach the result he desired. On the issues he truly seemed to care about, there always seemed to be a way to find that the framers of the Constitution thought exactly the same way Nino did.

*As one indication of how much I’ve changed, in a Con Law class a couple of years before Bork’s nomination to the Supreme Court I said that Bork should be canonized. My professor, who was not as big a fan, said I should be lobotomized.

@Kathy:

Specifically, it’s a terrible thing in a Supreme Court Justice.

It’s actually a great thing for the lawyers arguing before the Court, though. The brilliance we want from our Justices lies in how they grapple with the arguments laid out by plaintiffs, not in how they justify their own opinions.

The difference in physics, and indeed any science, or any reputable philosophy, is that the judgement comes by communal consensus: a lone radical may hold a contrary viewpoint that forces an entire community to think harder about the relevant questions and facts, but this is a good thing because it energizes the community. In law, that doesn’t work because while the community of lawyers may think very hard about those opinions, their reactions ultimately don’t matter for the determination of constitutionality: only the justices’ reactions matter, and there are only a dozen or so of them.

Even if we expanded the Court to 30 members, it would still not be enough to make this effect useful.

@dazedandconfused:

“Balls and strikes are very simple things”

Nope. Balls and strikes are incredibly complex and hard to figure out on the corners. It’s only when a pitch is grooved down the middle of the plate or thrown in the dirt or a foot outside that calling a ball or strike is simple. Every major league umpire has a slightly different strike zone, and it’s important for the players to know if the guy behind the plate has a high strike zone or a low strike zone, and whether he gives the corners to the pitcher or the batter. Roberts was exactly right when he said that judging was calling balls and strikes. The metaphor just didn’t mean what he pretended it meant.

@Jen:

Brilliant legal mind can also mean as an advocate, rather than an impartial justice. I have no doubt that Scalia’s interpretations of the law and the arguments he gave for them challenged RGB intellectually.

And only a few of them in a “how could anyone believe such legalistic argle bargle?”

I am willing to say that he was brilliant, but on the wrong side of the bench.

——

Oh, when I type “but” my iphone offers to complete with “Buttigieg” — how adorable!

Hmm. Buttigieg is brilliant, let’s put him on the court.

@Gustopher: Agreed. And as I’ve thought about this over the afternoon, I’ve settled more on the notion that Scalia and Ginsburg were probably friends precisely because they respected the challenge each presented the other.

Smart and secure people LIKE to be challenged, because they realize it makes them better–the more one understands of an opponent’s argument, the better one can determine how to lay waste to that argument.

Buttigieg is brilliant AND young, so I’m game. 😀

@Teve:

You remind me of how much I hate Posner’s writing style, and it confirms the experience of mattbernius‘s wife that appellate court opinions (Posner was on the 7th Circuit – my circuit) can be just as counterproductive as Supreme Court opinions.

But I will add, as a former district court clerk, it has always been my contention that I can find at least one district court opinion standing on any side of any proposition of law and I have rarely been disappointed.

Good Lord, what a prescription for disaster. I want nine competent and objective legal minds with as wide an education and practical experience of real life as possible. No amount of legal genius is going to help if you simply haven’t the background to understand the facts of the case, or if you have overriding prejudices. (No, being a legal genius does not inoculate against prejudice.)

@Roger:

Thank you; I didn’t have the background or data to make that point as well as you did.

@Roger:

Only by people.

Well, if I had to select only one justice to decide a case it would be Elena Kagan.

She has a model temperament, has an inclusive style, and she’s not a rigid ideologue. None of those traits can be ascribed to Kavanaugh, Alito or Thomas, and it’s too early to tell with Gorsuch and Barrett.

@Joe:

Also, thanks for that clarification. I was talking about the Appellate court versus the district courts.

Scalia was against flag burning then he was for it. His

“originilism” is full of holes as he often admits. Bush v. Gore is just flat out embarrassing. I could go on forever but whatev. As stated in Alice in Wonderland- first the verdict…

Souter, Lewis Powell and Kennedy were only possible because there were different parties controlling the White House and the Senate during their nominations. The ugliness of the Merrick Garland farce is creating a scenario where it’s only possible to confirm Justices when the same party controls both.

That’s going to be a huge problem in the future. By the way, HarvardLaw92 was really right about Beer Boy Kavanaugh.

@Andre Kenji de Sousa: I don’t remember what he said

@Roger:

The strike zone is only complicated for the hitters and pitchers, for the umpire it’s where he says it is and that’s that. No citations of old strike zones needed, and nobody cares what James Madison’s opinion might or might not have been on the matter, let alone pretend to know.

@David S.:

In the hard sciences, judgement ultimately comes from experiment and observation. Plate tectonics, the idea that continents move started as a loony toon idea going back at least to 1915, but the consensus was that the continents were fixed. After all, look at them. But, as you say, that got people to think about it, various observations accumulated that were consistent with continental drift, and finally around 1965 the consensus became, ‘Well I’ll be damned, they move.” Ultimately it wasn’t a matter of argument and contemplation, it was a matter of physical observation.

From what I read, consensus actually is important in the law. Judges want to be respected in the legal community. One of the explicitly stated goals of the Federalist Society is to create an “audience” (their word) that will influence the reactions of the Justices. From Amanda Hollis-Brusky Ideas With Consequences,

The strength of science is deniability. Wrong ideas can be shown to be wrong. In religion and law, there’s no comparable test, although the law does have real world consequences. We don’t say Dred Scott was wrong through legal analysis, we say it was wrong because it led to the Civil War. I wonder what disasters will eventually show our conservative Justices to have been wrong.

This, of course, is the dirty little secret (well, not so secret) of all the members of SCOTUS…conservatives talk a good game about not legislating from the bench, but all judges have their preferences and shape their decisions based on those preferences…Thurgood Marshall said his judicial approach was, “You do what you think is right and let the law catch up.” It would be refreshing if all judges admitted that this is basically what they do…

@Teve: I was thinking about this comment: https://www.outsidethebeltway.com/is-the-federalist-society-nefarious/#comment-2352865

He proved to be precise about Kavanaugh.

@Andre Kenji de Sousa: your search skills are impressive 😀

Prof. Joyner, thanks for the link, which renews my conviction to keep my old blog post online and available. Of course, I cite myself more often than anyone cites me, but I’m tickled and flattered to be remembered. I’m well enough, thank you for asking. But as you’ve noted, I haven’t been blogging in some time. If you were to infer that that might have something to do with Donald Trump’s hostile but necessarily temporary takeover of the GOP in 2016, you would not be wrong. I do still have this blog bookmarked and visit it from time to time, and I commend you on your patience and continued industry. I continue to find your opinions to be interesting and thought-provoking, and I continue to agree with you more than half of the time. Best regards to you & yours, and of course to all of OTB’s readers, especially those long-time readers who might vaguely recall my blog with the help of your reminder and link.

PS: My writing about the Miers nomination endeared me to no small number of my fellow members of the Texas Bar, and at least a handful of Texas trial and appellate judges, who believe, as I do, that the SCOTUS could benefit from the viewpoints brought by lawyers with significant private practice experience, and one of my fondest memories of the days when I was actively blogging was the assessment of someone at NRO to the effect that I’d done a better job of arguing the merits of the Miers nomination than the Bush White House did. It was a lost cause, but I have no regrets.

@Beldar: Good to hear from you!

While I studied political science with an intent to follow it with law school, I decided at the 11th hour that the only job in the legal profession that really interested me was Supreme Court Justice and that I was exceedingly unlikely to get there, so went on a different path. But I studied Constitutional Law quite a bit as an undergrad and in my masters program was very much a fan of Rehnquist and Scalia and modeled my view of the law and the court on them. Miers decidedly does not fit that model. But, as this post indicates, I’m starting to have strong doubts about the model—at least the notion that we should have nine Rehnquists and Scalias.

And, yes, I sympathize with the Trump era being tough for a principled conservative trying to catalog his thoughts publicly on a daily basis. It requires either defending the indefensible or becoming a one note Johnny like the Lincoln Project people. My output dropped considerably once I realized I was writing different versions of the same post every time out.

Certainly four or so, out of nine total, ought to be enough, right?

When I clerked on the Fifth Circuit, my judge — who was then in her second year on the bench, after a nonlitigation (securities law) private practice — would occasionally ask her clerks to read a draft majority opinion sent to her from another of the judges on one of her oral argument panels, to help her make a better-informed decision whether to indeed concur in that draft in full, or instead to write a separate concurring opinion, or even (much more rarely, at the circuit court level) a dissent. Inevitably, my co-clerks and I would find some angle, some particular, in the draft opinion with which we had quibbles or concerns, plus the native and naïve self-confidence of the young-20s just-out-of-law-school which led us to believe we could have written something “better.” (And sometimes we were even right about that!)

Sometimes, but quite rarely, she’d incorporate our thoughts and suggestions into a suggestion of her own, to the draft’s authoring judge, about a possible revision or tweak.

But most of the time, she didn’t. Although she was new to the bench, she’d already figured out — with the guidance of the fellow judges with whom she most quickly became close friends — that was overthinking her job. There was, and still is, a strong presumption against writing separate concurrences at the circuit court level — which is why, for example, if you look at the long period during which Merrick Garland and Brett Kavanaugh were literally sitting side-by-side on the D.C. Circuit (Kavanaugh being next most senior to Garland), you’ll find remarkably few dissents or even separate concurrences, and an overwhelming majority of simple concurrences-without-reservation in each others’ opinions. If, however, they’d both ended up on the SCOTUS, that probably would have ended.

I still believe that during his long Chief Justiceship, the most incredible accomplishment of Chief Justice Earl Warren was not the writing of Brown v. Board, but rather, securing the unrestricted concurrence of every other member of the Court. Never has the Supreme Court of the United States spoken more persuasively, or impactfully, as a direct result! Nine/zero decisions, with a single opinion for the Court, are still fairly frequent — but never on cases remotely as consequential. And I think that’s a shame.