West Shamed Into Action

Actions deemed unthinkable days earlier are suddenly mandatory.

At NYT, Mark Landler, Katrin Bennhold and Matina Stevis-Gridneff seek to explain what I continue to believe is the most remarkable outcome of the Ukraine invasion: “How the West Marshaled a Stunning Show of Unity Against Russia.”

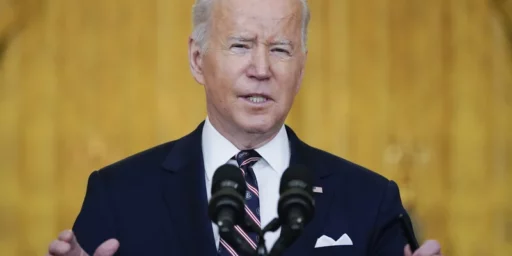

The day after Russian tanks and troops poured across the Ukrainian border on Feb. 24, NATO leaders received a deeply frightening message. The alliance’s secretary general, Jens Stoltenberg, opened an emergency video summit by warning that President Vladimir V. Putin had “shattered peace in Europe” and that from now on, he would openly contest the continent’s security order.

However unlikely, Mr. Stoltenberg told the leaders, it was no longer unthinkable that Mr. Putin would attack a NATO member. Such a move would trigger the collective defense clause in the North Atlantic Treaty, opening the door to the ultimate nightmare scenario: a direct military conflict with Russia.

President Biden, who had dialed in from the White House Situation Room, spoke up swiftly. Article 5 was “sacrosanct,” he said, referring to the “one for all, all for one” principle that has anchored NATO since its founding after World War II. Mr. Biden urged allied leaders to step up and send reinforcements to Europe’s eastern flank, according to multiple officials briefed on the call.

Within hours, NATO had mobilized its rapid response force, a kind of military SWAT team, for the first time in history to deter an enemy. It was one in an avalanche of precedent-shattering moves, unfolding in ministries and boardrooms from Washington to London and Brussels to Berlin. In a few frantic days, the West threw out the standard playbook that it had used for decades and instead marshaled a stunning show of unity against Russia’s brutal aggression in the heart of Europe.

We’ve discussed plenty the manifestations of this, including the Germans waking from a long slumber and sports leagues and businesses taking bold steps decidedly against their short-term interest. But how did it come about?

The report notes that Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky practically begged Western leaders for help at the Munich Security Conference late last month and privately met with US Vice President Kamala Harris, who gave him no assurances.

But then, suddenly, the German Chancellor Olaf Scholz announced the end of Nord Stream 2 in reaction to Putin’s declaration recognizing Donetsk and Luhansk. Two days later, when Putin announced his “special operation” in a bizarre speech, things seemed to click.

Until that moment, said Karen Pierce, the British ambassador to the United States: “I don’t think everyone in Europe and around the world expected it to be full-blown. That was the moment that jolted everyone.”

The European Union’s belated recognition was evident in the initially plodding negotiations over sanctions. A decade of crises — from eurozone debt problems to Brexit and the pandemic — had created an almost ritualistic pursuit of self-interest when it came to hammering out Europe-wide policy in Brussels.

[…]

But their resolve quickly stiffened with the start of the war. Shortly before Germany, the Netherlands offered Ukraine Stinger missiles and other weapons. Last Saturday, the European Union set up a nearly $500 million fund for members to send weapons. It was the first time the bloc jointly purchased lethal weapons to arm another country’s army under the E.U. banner — another Rubicon crossed.

“I don’t remember a time when the target of Western sanctions was so economically integrated into the West,” said Tom Keatinge, a senior researcher with the British Royal United Services Institute, a research group in London. Punishing Russia, he said, became an imperative for world leaders and everyday consumers. “It became about, ‘What are you, man on the street, going to sacrifice for Ukraine?'”

[…]

It was before dinner on Feb. 24, on the evening after the invasion began, when Mr. Zelensky’s image flickered on a video screen. European leaders were meeting under the highest level of secrecy, without advisers or electronic devices. Clad in suits and ties, they were seated in the comfort of a high-tech conference room in Brussels. Mr. Zelensky appeared to be in a bunker, somewhere in Kyiv, wearing his now-famous military-green T-shirt. The contrast was not lost on anyone in the room.

“This may be the last time you see me alive,” Mr. Zelensky said in making yet another fervent plea for tougher sanctions and more weapons.

When the leaders emerged from the room, they were visibly shaken, several officials said. Some described Mr. Zelensky’s appearance as a “catalyst” and a “game changer.” Later that night and the next morning, they instructed their envoys in Brussels to freeze the assets of Mr. Putin and Mr. Lavrov, and to finally greenlight the severing of many Russian banks from the SWIFT platform — concerted action against a country that had long divided them.

“It’s a quantum leap,” said Rosa Balfour, the director of Carnegie Europe. “Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has brought Europeans together on what probably has been the single most divisive foreign-policy issue since the start of the European Union.”

There was a similar evolution in the thinking of the Biden administration. The United States also had initial concerns about using SWIFT as a weapon. There could be unintended consequences, some officials argued, like driving Russia closer to China financially.

At the NATO emergency summit on Feb. 25, Mr. Johnson, the British prime minister, urged other leaders to suspend Russian banks from SWIFT. He was seconded by leaders from Poland, Latvia and the Czech Republic.

By the next day, the United States was on board, along with the European Union: They would penalize Russia’s central bank and remove some Russian institutions from the SWIFT system, choking off Russia’s access to a cushion of international reserves it had built up since first invading Ukraine in 2014.

Like Germany’s shuttering of the Nord Stream project, the action on SWIFT took Western penalties to an entirely new level.

It would seem that the contrast between Zelensky’s courage and their own reticence shamed Western leaders into action. But, as I’ve noted before, nothing of this sort comes without strong leadership from the United States and, this time, it was forthcoming. Indeed, it had been quietly happening behind the scenes for months.

The annexation of Crimea hung over American officials. Over breakfast at the security conference in Munich, Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken vividly recalled the mistakes made in 2014, when Western allies were taken by surprise by Russia’s lightning conquest. It took them nearly a year to cobble together sanctions, none of which were severe enough to force Mr. Putin to reverse himself.

Mr. Blinken, who worked for Mr. Biden, then the vice president, pushed for the United States to send Javelin antitank missiles to Ukrainian troops. But President Barack Obama, fearing a cycle of escalation with Moscow, resisted. Gathering foreign policy experts at a White House dinner in September 2014, Mr. Obama asked, “Will somebody tell me: What’s the American stake in Ukraine?”

Those memories stuck with Mr. Biden, who as vice president had visited Kyiv several times. Now, as president, he viewed Ukraine as a chance to reassert the United States’ leadership on the world stage — a role that had become tarnished after his administration’s chaotic, bloodstained departure from Afghanistan.

American diplomats had held hundreds of meetings with European officials since Russia began massing troops in the fall. In a striking break from practice, the C.I.A. disclosed detailed intelligence about Mr. Putin’s war plans, including so-called false-flag operations that Russia could use as a pretext to strike. That stripped Russia of any element of surprise, even if it did not cause Mr. Putin to rethink his course.

All of this seems to have set off a feeding frenzy in which those who had been feckless or indifferent in the past were suddenly racing to do more—and being shamed into doing more still.

As the images of burning buildings and fleeing Ukrainians filled screens around the world, the ripple effects of Russia’s invasion spread far beyond government ministries. For multinational companies like Apple, Google, BP and Shell, the costs of doing business in Russia suddenly became untenable.

Apple halted sales of iPhones and iPads, prompting a social media video of a Russian man smashing his iPad with a hammer. Google’s parent, Alphabet, said YouTube, which it owns, would suspend advertising on channels affiliated with state-funded Russian media groups. Google Maps stopped displaying real-time traffic information in Ukraine for fear that it could jeopardize the safety of people there.

It was a turnabout from previous episodes when Google and Apple acquiesced to Russia’s demand to alter how their digital maps demarcated the disputed Crimean Peninsula after Russia annexed it. Last year, both yielded to Russian pressure and removed an app created by allies of the jailed dissident leader Aleksei A. Navalny that was meant to coordinate protest voting during a parliamentary election.

But Google’s actions did not go far enough to satisfy European Union officials. In a video call, they urged Alphabet and YouTube’s chief executives to remove two Russian state-owned news agencies, RT and Sputnik, from YouTube altogether. Two days later, they did so.

Western oil giants were coming to a similar recognition. BP’s chief executive, Bernard Looney, knew his company would have to walk away from its $14 billion stake in Rosneft, a state-controlled Russian oil company, almost as soon as the invasion began, according to people with knowledge of the company.

Two days after Russia attacked, Mr. Looney held a videoconference with Britain’s business minister, Kwasi Kwarteng, who expressed the government’s concerns. By Sunday afternoon, BP’s board voted to exit the Rosneft holding, ending a foray into the rough-and-tumble world of Russian oil and gas that dated to 2003.

The prospect of Mr. Looney serving on the same board as Igor Sechin, the chief executive of Rosneft and a longtime confidant of Mr. Putin’s, would not have sat well with either the British government or people who fill up at BP’s gas stations.

There’s a lot more to the report but that’s the core of the “how” piece of it. It’s truly a stunning and remarkable development. And one that speaks to the power of norms in international relations.

Obama was being ruthlessly Realist eight years ago when he asked, “What’s the American stake in Ukraine?” He assessed, correctly in my view, that it was not sufficient to risk war with Russia. Indeed, Biden and the NATO allies continue to share that assessment.

Countries, business firms, and sporting leagues all have their own interests and cutting off a powerful, if corrupt and dangerous, country like Russia is costly to them. While I think, for example, that Russia should long ago have been banned from the Olympics, I don’t at all blame Apple or Google for being unwilling to deny themselves a lucrative market until now.

And yet, almost instantly, the perception of these interests changed for all these actors simultaneously.

The United States and its NATO allies are still not willing to go to war with Russia. Or even to declare Ukraine a no-fly zone, which is a step just shy of that. But they’re suddenly willing to take measures they would have balked at even ten days ago. And, again, it seems that they have been shamed into it, seeing their honor as tied to standing up to Putin.

The blatant war of conquest for what can only be described as imperialist purposes has shocked a world system that no longer sees such actions as acceptable state action.

If Putin had contented himself with annexing parts of eastern Ukraine and slowly pressuring independent Ukraine from growing ties to the west, he could very easily have gotten away with it (as he did in Crimea and as he has in parts of Georgia).

BTW: while I think that a lot of these actions (like BP’s, to pick one) are about avoiding shame in the long run, I am not sure that what we are seeing is actors being shamed into action. I think we are seeing a set of state and non-state actors acknowledging that the basic structure of the global order, which eschews wars of conquest, is one that they all want to maintain.

I think this is all what happens in a world of true global interdependence based largely on broadly-defined liberal notions of politics. You can’t make money or live your life if people like Putin are allowed to roll the tanks in. He went too far and the system is reacting.

I don’t think the ball is in our court as far IF the west goes to war with Russia. I think Putin want a war with the west and will goad us until we respond. But the greater question in my mind is: Why?

@Skookum:

_as far as IF_

@Skookum:

Surely he must know the consequences of a nuclear war, which it would be, and which he has threatened.

The “power of norms” being demonstrated here (including the shaming – which is basically a public calling to abide by established norms) are, to my mind, a major affirmation of liberal democracy.

Norms in this era of liberal democracy are essentially the “public will” over time. We are seeing governments responding to the wants of their constituencies. We are seeing corporations are responding to the will of their customers and their employees.

It is refreshing to see that sometimes what the people want is listened to despite all the systematic obstacles in the way.

One should be fair, there was a reasonable question mark, was Ukrainian own resolve there? Was the Russophone east aligned with national identity or was the more like Afghanistan, a central state fiction? One could have reasonable doubts, especially after the Afghanistan fiasco (although the similarities are really superficial). See comments by Andy at start (reasonable ones).

What the first days said was, oh, there’s a real actual Ukrainian will to resist and even in the Russophone East.

If one is going to take geopolitical risks, much easier if one sees that there’s a real domestic spine…. contra again Afghanistan.

I’m with @Lounsbury on this. It was crucial that Ukraine was willing to fight. That’s what has made the difference. That and the sheer scale of Putin’s evil intent.

@Steven L. Taylor:

His goal may still be just the eastern, traditionally Russian parts. Or at least his fall-back position. The actions in the north still serve to split Ukrainian forces. It appears mostly conscripts were used in the north, and it got piss-poor logistical planning. It seems a lot of effort is going into taking a land bridge to Crimea so they no longer have to use that ridiculous bridge on the Azov side.

Imperialism? Perhaps, but it should be kept in mind Ukraine was not considered one of the bloc states of the USSR, and the eastern parts were added to Ukraine as an administrative simplification by the USSR, even though they spoke different languages in the oblasts. There is a distinct possibility Putin has no ambitions beyond that. Certainly he doesn’t have the kind of military or rabid public support that Hitler had, and we live in the age of nukes.

Shamed into it, or seeing that it might help?

The expectation was that Ukraine would likely be lost in 3 days if Putin went for the all out assault that the Biden administration was saying was likely. Sue to the amazing staggering incompetence of the invasion, and the Ukraine’s equally amazing resistance, there’s actually hope that this can be turned back.

That’s not the same thing as shame.

We’re resupplying the Ukrainians, and that wasn’t on the table initially because everyone figured they wouldn’t last long enough to take delivery.

And it puts greater urgency on stronger actions now, rather than allowing weaker sanctions to stay in place for years to weaken Russia and hold back further aggression.

@Gustopher: As I commented, prior to the opening it was not unreasonable to have real doubts if stepping up for Ukraine made sense.

Actor as President, adminstration of which had queerly minimising Russian invasion preps, large native Russian speaking majority in the Eastern provinces. Doubts about whether this population supported in reality the Ukranian state.

Doubts about willingness to fight – and impact of the recent (not really directly applicable but one has to say mentally it impacted) Afghan collapse.

Then you had three days of “holy shit, they fight like demons, and the Presdient didn’t run away.”

I think I agree, this is not the same thing as shamed (although for Germany that applies clearly), it’s as much seeing, “ah, they do have the spine, it’s worth it” which was a very legitimate (if maybe not fair) question two weeks ago.

@Lounsbury:

So poor intelligence, intelligence failure (if/where that is the case)

@charon: no not poor intelligence, real doubts.

Poor intelligence was Putin’s jumping to strong conclusions and developing a war plan based on maximal conclusions draw from minimal basis.

But having doubts as the the solidity of the Ukranian regime, how the adminstration would hold up, how the population in the east might break, that’s not bad intelligence, that’s reasonable doubt.

@charon: I don’t think anyone could reasonably anticipate the Russian forces doing such an amazingly poor job.

A convoy basically out of gas, on a narrow road, surrounded by mud so they cannot get supplies in?

If we weren’t seeing pictures of it, and satellite imagery, I would assume it was fake news generated by Ukraine for propaganda. Really over the top propaganda.

Russian military vehicles being hauled off by farmers with tractors? (Ok, that might be staged)

Russian troops engaging in a firefight against a tank in an old war memorial? (A real tank, at least, rather than a statue)

I don’t want to minimize the Ukrainian people’s efforts, which are amazing, but they’re up against one of the greatest military blunders in the modern era. They are seizing the opportunities they get, as best they can, and we should help them however we can without supplying troops, or putting Americans on the ground or in the airspace.

But, the safe bet was that by now Russian’s puppet would be in charge and signing a new security arrangement with the Russians.

——

Was someone deliberately screwing up the planning? Have the Russian forces been hollowed out due to corruption? Both? And more?

@Steven L. Taylor: My cousin recently retired from Chevron. During her years there, she did at least one extended assignment (lasting several years) in Russia beginning in the perestroika/glasnost era. The theory of our government at the time, to the extent that I can recall, was that it served no purpose to treat a reforming system as the pariah state that had preceded it. It was probably the right choice for the time. I wish it had worked better. The best we can do is try.

@Gustopher:

Oh, I agree the poor performance of the Russians was surprising, how badly overrated they were. Also, how poor the Russian battle plan was, including the troops being surprised to find out they were going to Ukraine, and that they were not on a training deployment. Massive cockup, beyond any reasonable expectation.

But, anyone who doubted Ukraine people would fight and fight hard was just badly informed. That IMO is an intelligence failure.

Putin appears to have believed his own ideological propaganda about the fragility of Ukraine, the superficiality of it’s national identity, and the “natural” allegiance of Russian speakers to the Russian state.

If apparent reality failed to correspond with this deeper “truth” that Putin and and the Great Russia nationalists, then it could be made to by Force and Will.

What should have made him think twice was the complete absence of popular agitation for union with Russia even in Donbas. Or indeed Crimea.

As I keep on repeating, in Ukraine Russian speaking does not equate to identifying as Russian; and identifying as Russian does not equate to wishing for the rule of the Russian state.

Even if Putin “takes” the south east, what happens if the “Russians” there say “NO!”.

There are plenty of indications that in the Russian held parts of Donetsk/Luhansk the “anti-Ukraine” movement was created and sustained primarily by a combination of local mafiya/oligarch “militias”, the Russian Special Forces “little green men”, and far-right irregulars.

It is notable that among the first actions of the secessionists in 2014 was to prevent voting in the national elections, and that nearly a million people fled or were evicted by the Russian forces.

The likelihood of Russia being able to hold even a section of the east long term are not very good.

No matter how much Putin and the Great Russia fanatics may rage about it.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Avoiding shame or just avoiding risk? I suspect the latter, as oil companies have traditionally shown no ability to be shamed.

Sanctions on a growing number of Russian products, and the expectation of more if the Russian government doesn’t change course, are more likely to affect oil companies than pictures of refugees and shelled cities.

@charon: Your IMO is ideology speaking and misframing of the observations. The doubts were not “would (an abstract Ukrainian people) fight” but how Eastern Ukrainian Russophone would break, and if the Actor President Administration would hold. Those were reasonable question marks for rational non emotional sentiments based analysis, even if one suspected yes.

“…nothing of this sort comes without strong leadership from the United States and, this time, it was forthcoming.

OH, you mean Biden’s continuing purchases of Russian oil and just today, he has made oil purchase overtures to Saudi Arabia and Venezuela. That kind of leadership? Saw joke poster on another blog: The oil is in Texas but the dipstick is in D.C.