First Quarter Economic Growth Better Than Initially Forecast, But Further Slowing Is Forecast

Economic growth in the first quarter wasn't as bad as first estimated, but it still wasn't very good. And the future is unclear at best.

Yesterday’s report on the second estimate of first quarter Gross Domestic Product revealed that the economy slowed less than expected, but the numbers still weren’t great and the future is, at best, murky:

Real gross domestic product (GDP) increased at an annual rate of 1.2 percent in the first quarter of 2017 quarter, real GDP increased 2.1 percent.

The GDP estimate released today is based on more complete source data than were available for the ”advance” estimate issued last month. In the advance estimate, the increase in real GDP was 0.7 percent. With this second estimate for the first quarter, the general picture of economic growth remains the same; increases in nonresidential fixed investment and in personal consumption expenditures (PCE) were larger and the decrease in state and local government spending was smaller than previouslyestimated. These revisions were partly offset by a larger decrease in private inventory investment (see ”Updates to GDP” on page 2).

Real gross domestic income (GDI) increased 0.9 percent in the first quarter, in contrast to a decrease of 1.4 percent (revised) in the fourth. The average of real GDP and real GDI, a supplemental measure of U.S. economic activity that equally weights GDP and GDI, increased 1.0 percent in the first quarter, compared with an increase of 0.3 percent in the fourth quarter (table 1).

(…)

The increase in real GDP in the first quarter reflected positive contributions from nonresidential fixed investment, exports, residential fixed investment, and PCE that were partly offset by negative contributions from private inventory investment, federal government spending, and state and local government spending. Imports, which are a subtraction in the calculation of GDP, increased (table 2).

The deceleration in real GDP in the first quarter primarily reflected a downturn in private inventory investment and a deceleration in PCE that were partly offset by an upturn in exports and an acceleration in nonresidential fixed investment.

Current-dollar GDP increased 3.4 percent, or $158.2 billion, in the first quarter to a level of $19,027.6 billion. In the fourth quarter, current-dollar GDP increased 4.2 percent, or $194.1 billion (table 1 and table 3).

The price index for gross domestic purchases increased 2.6 percent in the first quarter, compared with an increase of 2.0 percent in the fourth quarter (table 4). The PCE price index increased 2.4 percent, compared with an increase of 2.0 percent. Excluding food and energy prices, the PCE price index

increased 2.1 percent, compared with an increase of 1.3 percent (appendix table A).

The 1.5% growth estimate in this second report is definitively an improvement over the initial report that Gross Domestic Product had only increased 0.7% in the first three months of the year, but it’s still not exactly the kind of robust growth that we need to keep the economy growing at anywhere near an acceptable pace. As it is, the recovery that we have been in since roughly the summer of 2009 has included some of the slowest growth of any recovery since World War II, and even included a few random quarters where the economy actually shrank. For the most part, this is meant that average economic growth for the past eight years has been roughly between 2.0% and 2.5%. Granted, this is better than most first world economies have done over a comparable period, but its far from the ideal of at least 2.5% to 3.0%, or better, that we ought to be seeing.

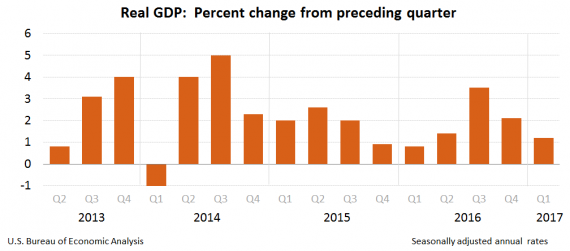

It’s also worth noting the fact that one of the characteristics of the recovery has been the fact that first quarter has been the weakest in any given year for a large part of the period between 2009 and today. In many of those quarters have been explained as having been impacted by severe winter weather that caused businesses to be closed or slowed down for extended periods of time over large areas. That wasn’t really the case this year, however. For the most part, the nation experienced an average winter with very few crippling storms. Granted, it was cold in many parts of the country and this likely kept consumers home rather than shopping, but snowfall was basically average and, especially in the Northeast and Middle Atlantic, there were fewer major storms than we had seen in recent years. In any case, the pattern of a slow first quarter has been rather consistent going back several years, as this chart that accompanied Friday’s report shows:

In previous years the economy has largely bounced back after the seemingly traditional first quarter slump, but as The New York Times notes, the outlook for the future this year is cloudy at best:

WASHINGTON — The U.S. economy slowed less than initially thought in the first quarter, but softening business investment and moderate consumer spending are clouding expectations of a sharp acceleration in the second quarter.

Gross domestic product increased at a 1.2 percent annual rate instead of the 0.7 percent pace reported last month, the Commerce Department said on Friday in its second GDP estimate for the first three months of the year.

That was the worst performance in a year and followed a 2.1 percent growth rate in the fourth quarter.

“Economic indicators so far aren’t entirely convincing on a second-quarter bounce in activity and show a U.S. economy struggling to surprise on the upside,” said Scott Anderson, chief economist at Bank of the West in San Francisco.

The first-quarter weakness is a blow to President Donald Trump’s ambitious goal to sharply boost economic growth.

During the 2016 presidential campaign Trump had vowed to lift annual GDP growth to 4 percent, though administration officials now see 3 percent as more realistic.

Trump has proposed a range of measures to spur faster growth, including corporate and individual tax cuts. But analysts are skeptical that fiscal stimulus, if it materializes, will fire up the economy given weak productivity and labor shortages in some areas.

“If the economy is going to grow at 3 percent for as long as the eye can see, businesses better spend lots of money on capital goods. That is not happening,” said Joel Naroff, chief economist at Naroff Economic Advisors in Holland, Pennsylvania.

The economy’s sluggishness, however, is probably not a true reflection of its health, as first-quarter GDP tends to underperform because of difficulties with the calculation of data that the government is working to resolve.

The government raised its initial estimate of consumer spending growth for the first quarter, but said inventory investment was far smaller than previously reported. The trade deficit also was a bit smaller than estimated last month.

Economists had expected that GDP growth would be revised up to a 0.9 percent rate. Despite the tepid growth, the Federal Reserve is expected to raise interest rates next month.

Some analysts, such as Andy Pudzer, an economic analyst who withdrew as President Trump’s nominee for Labor Secretary in February, argues that the economy is “markedly improving”, but that certainly doesn’t seem to be showing up in the data so far and, as Ed Morrissey notes, the prospects for the kind of economic growth that the Trump Administration is depending on for any of its legislative agenda to meet budget estimates seems optimistic, to say the least:

The problem starts with an assumption built into the financial projections of the budget proposal from OMB chief Mick Mulvaney. Donald Trump campaigned on a promise to enact economic policies that would produce annual growth in gross domestic product (GDP) consistently higher than 3 percent. The US economy has not seen that level of growth in a single year since 2004, and not in consecutive years since the dot-com bubble period of 1996-2000, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, but that promise was key to Trump’s election – and he has to deliver on it to pay for some of his other initiatives.

That may be the problem. Mulvaney’s budget assumes an even higher level of growth over the next ten years. The Trump budget projects a constant rate of real GDP growth of 3 percent from 2021 to 2027, a rate that has not been sustained for that long in the last several decades, at least. As CNN Money notes, the 2004 peak came as part of the housing bubble and since the collapse, has never come close to sustained growth at that rate. …

Unfortunately, in this case, the extreme nature of the underlying assumptions of the budget, combined with the duplicative use of questionable revenue outcomes, undermines the credibility of this big ask. The pay-for on tax reform relies on a sustained rate of growth that the US hasn’t seen for a single year in two decades, which makes the cuts to safety-net programs a greater risk. The math doesn’t add up.

In no small part because of its unrealistic economic projections, the budget proposal that Trump submitted is already considered dead on arrival even by Republicans. If those projections aren’t met, it’s going to seem like an even bigger joke. So far, it’s looking like we won’t even come close.

Must be a mistake. All o my conservative friends have assured me the economy is doing much better now that Trump is president.

Steve

We’re all Kansans now.

Trump will tweet that eco growth is huge and take credit.

A serious non-snarky question: how are non-shrink-wrap software and other intangible goods accounted for in this figure? I have seen some evidence that the traditional methods for computing GDP don’t handle them very well.