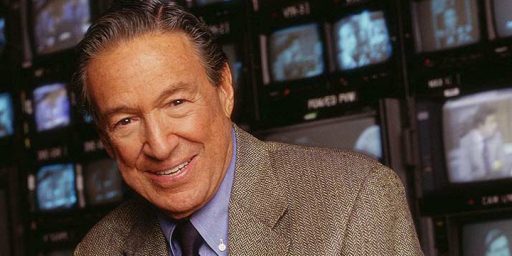

Morley Safer, Legendary 60 Minutes Correspondent, Dies At 84

A journalistic legend has passed away just days after his retirement was officially announced.

Morley Safer, who had been part of the hard-hitting group of reporters that called CBS News’s 60 Minutes home since joining the show in its third season, has died at the age of 84:

Morley Safer, a CBS television correspondent who brought the horrors of the Vietnam War into the living rooms of America in the 1960s and was a mainstay of the network’s news magazine “60 Minutes” for nearly 50 years, died on Thursday in Manhattan. He was 84.

CBS announced his death but did not give other details.

Mr. Safer was one of television’s most celebrated journalists, a durable reporter familiar to millions on “60 Minutes,” the Sunday night staple whose signature was a relentlessly ticking stopwatch. By the time he retired this year in May, Mr. Safer had broadcast 919 “60 Minutes” reports, profiling international heroes and villains, exposing scams and corruption, giving voice to whistle-blowers and chronicling the trends of an ever-changing America.

Mr. Safer joined the show in 1970, two years after its inception, and eventually outlasted the tenures of his colleagues Mike Wallace, Dan Rather, Harry Reasoner, Ed Bradley and Andy Rooney, becoming the senior star of a new repertory of reporters on what has endured for decades as the most popular and profitable news program on television.

But to an earlier generation of Americans, and to many colleagues and competitors, he was regarded as the best television journalist of the Vietnam era, an adventurer whose vivid reports exposed the nation to the hard realities of what the writer Michael J. Arlen, in the title of his 1969 book, called “The Living Room War.”

With David Halberstam of The New York Times, Stanley Karnow of The Washington Post and a few other print reporters, Mr. Safer shunned the censored, euphemistic Saigon press briefings they called the “five o’clock follies” and got out with the troops. Mr. Safer and his Vietnamese cameraman Ha Thuc Can gave Americans powerful close-ups of firefights and search-and-destroy missions filmed hours before air time. The news team’s helicopter was shot down once, but they were unhurt and undeterred.

In August 1965, Mr. Safer covered an attack on the hamlet of Cam Ne in the Central Highlands, which intelligence had identified as a Vietcong sanctuary, though it had been abandoned by the enemy before the Americans moved in. Mr. Safer’s account depicted Marines, facing no resistance, firing rockets and machine guns into the hamlet; torching its thatched huts with flame throwers, grenades and cigarette lighters as old men and women begged them to stop; then destroying rice stores as the villagers were led away sobbing.

“This is what the war in Vietnam is all about,” he reported. “The Vietcong were long gone. The action wounded three women, killed one baby, wounded one Marine and netted four old men as prisoners. Today’s operation is the frustration of Vietnam in miniature. To a Vietnamese peasant whose home means a lifetime of backbreaking labor, it will take more than presidential promises to convince him that we are on his side.”

Broadcast on the “CBS Evening News” with Walter Cronkite and widely disseminated, the report and its images stunned Americans and were among the most famous television portraits of the war. They provoked an angry outburst from President Lyndon B. Johnson, who excoriated Frank Stanton, the president of CBS, in a midnight phone call and ordered Mr. Safer investigated as a possible Communist. He was cleared.

For three weeks in 1967, Mr. Safer toured China, then in the throes of Mao Zedong’s cultural revolution, posing as a Canadian tourist (he was born in Canada) because Western reporters were banned. Then, as CBS London bureau chief, he covered a war in the Middle East, the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, strife in Northern Ireland and civil war in Nigeria, where he was expelled for reporting thefts from relief supplies intended for Biafran refugees.

In 1970 he swapped the foreign correspondent’s fatigues for the dapper suits and silk handkerchiefs of “60 Minutes,” American TV’s first news and entertainment hybrid with a magazine format, and was soon contributing celebrity interviews and stylish essays to complement the investigative exposés of Mr. Wallace, the veteran CBS inquisitor, who died in April 2012..

Over the next four decades Mr. Safer profiled writers, politicians, opera stars, homeless people and the unemployed, and produced features on shoddy building practices, strip mining, victims of bureaucracy, waterfront crime, Swiss bank accounts, heart attack treatments, problems of sleeplessness, cultural nabobs and other subjects, many suggested by staffers and viewers.

In contrast to the often abrasive Mr. Wallace, Mr. Safer produced witty pieces on the lighter side of life: the game of croquet, Tupperware parties, children’s beauty pageants, experiments to communicate with apes, and oil-rich Abu Dhabi, capital of the United Arab Emirates, “a place,” as he put it, “with free housing, free furniture, free color television, free electricity, free telephones, no property taxes, no sales taxes — no taxes, period.”

His serious journalism included a 1983 investigative report in which he cited new evidence that helped free Lenell Geter, a black engineer wrongly convicted of an armed robbery and sentenced to life in prison in Texas. Mr. Safer’s report was not the first on the case, but it drew national attention that led to its official reconsideration.

In the studio or reporting on the road — he often traveled 200,000 miles a year for “60 Minutes” — Mr. Safer was an affable interviewer, asking questions the man in the street might if he had the chance. He was well aware of television’s power to exploit emotions and was typically moderate, if persistent, in his commentaries.

(…)

Morley Safer was born in Toronto on Nov, 8, 1931, the son of Max and Anna Cohn Safer. His father owned an upholstery shop. He studied at the University of Western Ontario, was a reporter for two small newspapers in Ontario and worked for Reuters in London before joining the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation in 1955.

As a CBC correspondent over the next three years, he covered conflicts in the Middle East and Cyprus and the Algerian revolution. In 1958, he produced and appeared on “CBC News Magazine.” Sent to CBC’s London bureau in 1961, he covered major events in Europe, the Middle East and Africa in the early 1960s.

He joined the CBS London bureau in 1964, and in 1965 he went to Vietnam and soon began filing reports that changed the way many Americans perceived the war.

In 1968 he married Jane Fearer, an anthropologist and author. They had a daughter, Sarah. There was no immediate word on his survivors.

In 1989 Mr. Safer went back to Vietnam for a “60 Minutes” report and interviewed people whose lives had been touched by the war. He also wrote a best seller, “Flashbacks: On Returning to Vietnam” (1990), with a chapter on Pham Xuan An, a Time magazine war correspondent who had secretly spied for Hanoi. Mr. Safer held no grudges. “He has done his best to follow his conscience,” he wrote.

Mr. Safer won many awards, including Emmys, Peabodys and the George Polk Award for career achievement. In recent years he had worked part time for “60 Minutes.” Still, his 2009 profile of the legendary Vogue editor Anna Wintour, who rarely gave interviews, was the talk of the fashion world.

When he retired, CBS broadcast an hourlong special, “Morley Safer: A Reporter’s Life,” in which he revealed that he had not really liked being on television.

“It makes me uneasy,” he said. “It is not natural to be talking to a piece of machinery. But the money is very good.”

CBS News, of course, has its own tribute as well as an obituary:

Morley Safer, the CBS newsman who changed war reporting forever when he showed GIs burning the huts of Vietnamese villagers and went on to become the iconic 60 Minutescorrespondent whose stylish stories on America’s most-watched news program made him one of television’s most enduring stars, died today in Manhattan. He was 84. He had homes in Manhattan and Chester, Conn.

Safer was in declining health when he announced his retirement last week; CBS News broadcast a long-planned special hour to honor the occasion on Sunday May 15 that he watched in his home.

A huge presence on 60 Minutes for 46 years — Safer enjoyed the longest run anyone ever had on primetime network television. Though he cut back a decade ago, he still appeared regularly until recently, captivating audiences with his signature stories on art, science and culture. A dashing figure in his checked shirt, polka dot tie and pocket square, Morley Safer — even his name had panache — was in his true element playing pool with Jackie Gleason, delivering one of his elegant essays aboard the Orient Express or riffing on Anna Wintour, but he also asked the tough questions and did the big stories. In 2011, over 18.5 million people watched him ask Ruth Madoff how she could not have known her husband Bernard was running a billion-dollar Ponzi scheme. The interview was headline news and water cooler talk for days.

In some of his later 60 Minutes pieces, Safer profiled the cartoonists of The New Yorker, interviewed the founder and staff of Wikipedia and reported on a billion-dollar art trove discovered in a Munich apartment. In his last story broadcast on March 13, he profiled the visionary architect Bjarke Ingels.

“This is a very sad day for all of us at 60 Minutes and CBS News. Morley was a fixture, one of our pillars, and an inspiration in many ways. He was a master storyteller, a gentleman and a wonderful friend. We will miss him very much,” said Jeff Fager, the executive producer of 60 Minutes and Safer’s close friend and one-time 60 Minutes producer.

CBS News President David Rhodes said, “Morley Safer helped create the CBS News we know today. No correspondent had more extraordinary range, from war reporting to coverage of every aspect of modern culture. His writing alone defined original reporting. Everyone at CBS News will sorely miss Morley.”

Safer was a familiar reporter to millions when he replaced Harry Reasoner on 60 Minutes in 1970. A much-honored foreign correspondent, Safer was the first U.S. network newsman to film a report inside Communist China. He appeared regularly on the CBS Evening News from all over the world, especially Vietnam, where his controversial reporting earned him peer praise and government condemnation.

Safer’s piece from the Vietnamese hamlet of Cam Ne in August of 1965 showing U.S. Marines burning the villagers’ thatched huts was cited by New York University as one of the 20th century’s best pieces of American journalism. Some believe this report freed other journalists to stop censoring themselves and tell the raw truth about war. The controversial report on the “CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite” earned Safer a George Polk award and angered President Lyndon Johnson so much, he reportedly called CBS President Frank Stanton and said, “Your boys shat on the American flag yesterday.” Some Marines are said to have threatened Safer, but others thanked him for exposing a cruel tactic. Safer said that the pentagon treated him with contempt for the rest of his life.

He spent three tours (1964-’66) as head of the CBS Saigon bureau. His helicopter was shot down in a 1965 battle, after which Safer continued to report under fire. In 1990, he penned a memoir of his Vietnam experience, “Flashbacks: On Returning to Vietnam” (Random House), in which he goes back to reminisce and to interview the enemy’s veterans.

When he joined Mike Wallace at the beginning of 60 Minutes’ third season, they toiled to put stories on the air for a program that dodged cancellation each season. But their work was immediately recognized with an Emmy for Safer’s 1971 investigation of the Gulf of Tonkin incident that began America’s war in Vietnam. The two pressed on for five years, moving the broadcast from the bottom fourth to the middle of the rankings. Then in August 1975, with a new Sunday evening timeslot, Safer put 60 Minutes on the national stage. Interviewing Betty Ford, the first lady shocked many Americans by saying she would think it normal if her 18-year-old daughter were having sex. The historic sit-down also included frank talk about pot and abortion.

By 1978, the broadcast was in Nielsen’s Top 10. Safer’s eloquent, sometimes quirky features balanced out the program’s “gotcha” interviews and investigations, perfecting the news magazine’s recipe. It became the number-one program for the 1979-’80 season – a crown it won five times. 60 Minutes remained in the top 10 for an unprecedented 23 straight seasons.

It was another Safer story that would become one of the program’s most honored and important. “Lenell Geter’s in Jail,” about a young black man serving life for armed robbery in Texas, overturned Geter’s conviction 10 days after the December 1983 segment exposed a sloppy rush to injustice. Safer and 60 Minutes were honored with the industry’s highest accolades: the Peabody, George Polk and duPont-Columbia University awards. 60 Minutes founder Don Hewitt often pointed to the story as the program’s finest work.

Safer hit more journalistic home runs, but sought out the odd stories that piqued his curiosity. The offbeat tales were more suited to his raconteur style and cultural sensibility. He found esoteric subjects all over the world and here in the U.S., ranging from a tiny Pacific island nation economically dependent on guano to the strange choice of tango dancing as a national hobby for the shy people of Finland to the strange yet harmonious stew of cowboys and artists in the Texas town of Marfa — all narrated in his drolly delivered and precise prose. His conversational wit with his subjects was just as sharp as his written word. In a profile of the prim Martha Stewart, a smirking Safer passed her livestock pen and said to the domestic diva, “Your barnyard? It’s remarkably odor-free.”

Some of these features had national impact, however, like his November 1991 report, “The French Paradox,” which connected red wine consumption to lower incidents of heart disease among the free-eating French. Wine merchants say this report was single-handedly responsible for starting the red wine boom in America. His 1993 segment “Yes, But is it Art?”enraged the modern art community when it criticized expensive, contemporary installations featuring household items like toilets and vacuums. The Museum of Modern Art in New York City may have held a grudge; years later, it refused to allow Safer onto its premises to review a Jackson Pollock retrospective for CBS Sunday Morning.

(…)

Safer was asked to characterize his legacy as a journalist in a November 2000 interview with the American Archive of Television. “I have a pretty solid body of work that emphasized the words, emphasized ideas and the craft of writing for this medium. It’s not literary, I wouldn’t presume to suggest that. But I think you can elevate it a little bit sometimes with the most important part of the medium, which is what people are saying — whether they’re the people being interviewed or the guy who’s telling the story. It’s not literature, but it can be very classy journalism.”

Watching 60 Minutes was something of a tradition in my house growing up and Safer’s reports were always informative, entertaining, and, although they lacked the hard hitting confrontational style of Mike Wallace, always helped a viewer learn something new about whatever subject he happened to be covering that week. At times, it seemed as though is less confrontational style helped to lull interviewees expecting something in the style of Wallace into a false sense of security only to come back and catch them in the end. Additionally, his reporting on the arts and cultural matters brought a breadth to the show that worked nicely in conjunction with the more serious topics that a correspondent like Wallace might be covering. Whether it was investigative reporting or a profile of a newly prominent artist, though, Safer brought the same desire for completeness to all of his reporting, and it helped to make 60 Minutes, which was still very much struggling when he joined the show in 1970, into the institution that it remains today in younger hands. With his passing, the legendary cast of original hosts and reporters — which included luminaries such as Mike Wallace, Ed Bradley, Harry Reasoner, and Andy Rooney — has largely passed away, but the legacy they left behind remains.

In this video, Safer talks about his famous 1965 report on the Marine attack on the village of Cahm Ne:

And here is the career retrospective that CBS broadcast just this past Sunday to mark Safer’s retirement:

Safer was fantastic. When I´m 80 years old I want to have only 1% of the sagacity that he had in the last few years.

How sad What a great guy, It`s strange how Andy Rooney died just weeks after his retirement too

Wow only 2 comments for a renowned newsman A man who risked his life on the battlefields to bring you all stories. RIP