Elections with Foregone Conclusions

Greatest democracy in the world, right?

Regular readers will hardly be surprised by this piece in the NYT: ‘Taking the Voters Out of the Equation’: How the Parties Are Killing Competition

The number of competitive congressional districts is on track to dive near — and possibly below — the lowest level in at least three decades, as Republicans and Democrats draw new political maps designed to ensure that the vast majority of House races are over before the general election starts.

With two-thirds of the new boundaries set, mapmakers are on pace to draw fewer than 40 seats — out of 435 — that are considered competitive based on the 2020 presidential election results, according to a New York Times analysis of election data. Ten years ago that number was 73.

The core concept of representative democracy is that elected officials can be held accountable (i.e., can lose their seats) if they don’t adequately represent the voters. If most seats are foregone conclusions, that feedback loop is broken. Moreover, as I noted yesterday, it means that most elections are dictated by primary voters who are a small slice of the electorate made up of a non-representative sliver of the population.

If less than 10% of the US House is elected in competitive elections, then in what way are we a representative democracy? If politicians only have to please the primary electorate to stay in office, then the system will serve, at best, the interests of those voters and not have any incentive to serve broader preferences.

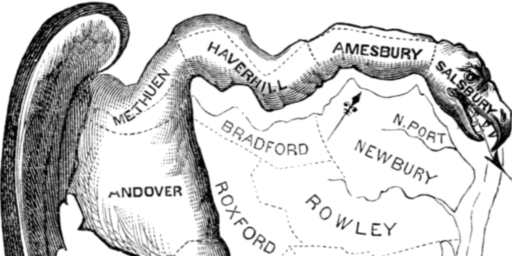

The core pathology in our system is the usage of single-seat districts to elect legislative bodies because such systems have inherent structural limitations and, moreover, are easily manipulated (and the relatively small size of the House exacerbates the problem).

Both Republicans and Democrats are responsible for adding to the tally of safe seats. Over decades, the parties have deftly used the redistricting process to create districts dominated by voters from one party or to bolster incumbents.

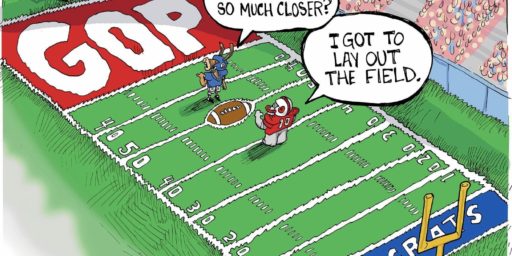

It’s not yet clear which party will ultimately benefit more from this year’s bumper crop of safe seats, or whether President Biden’s sagging approval ratings might endanger Democrats whose districts haven’t been considered competitive. Republicans control the mapmaking for more than twice as many districts as Democrats, leaving many in the G.O.P. to believe that the party can take back the House majority after four years of Democratic control largely by drawing favorable seats.

But Democrats have used their power to gerrymander more aggressively than expected. In New York, for example, the Democratic-controlled Legislature on Wednesday approved a map that gives the party a strong chance of flipping as many as three House seats currently held by Republicans.

That has left Republicans and Democrats essentially at a draw, with two big outstanding unknowns: Florida’s 28 seats, increasingly the subject of Republican infighting, are still unsettled and several court cases in other states could send lawmakers back to the drawing board.

“Democrats in New York are gerrymandering like the House depends on it,” said Adam Kincaid, the executive director of the National Republican Redistricting Trust, the party’s main mapmaking organization. “Republican legislators shouldn’t be afraid to legally press their political advantage where they have control.”

And before someone accuses me of “bothsiderism” the reality is that this is a case of both sides doing it because the system incentivizes it. The only way to stop it would be to go to multi-seat districts with some form of proportional representation. (The broader question of which party is more pro- or anti-democracy is a separate and important one, but it really doesn’t change the issue at hand in this post.)

To my point about the importance of primaries, the piece notes:

Without that competition from outside the party, many politicians are beginning to see the biggest threat to their careers as coming from within.

“When I was a member of Congress, most members woke up concerned about a general election,” said former Representative Steve Israel of New York, who led the House Democrats’ campaign committee during the last redistricting cycle. “Now they wake up worried about a primary opponent.”

Mr. Israel, who left Congress in 2017 and now owns a bookstore on Long Island, recalled Republicans telling him they would like to vote for Democratic priorities like gun control but feared a backlash from their party’s base. House Democrats, Mr. Israel said, would like to address issues such as Social Security and Medicare reform, but understand that doing so would draw a robust primary challenge from the party’s left wing.

Members of Congress know that to keep their jobs they don’t need to represent the interests of their district as a whole. Rather, they know that they need to please primary voters (it is part of why so many in Congress are downplaying 1/6). This makes the House unrepresentative.

Here’s a chilling (IMO) way of putting it all:

“The parties are contributing to more and more single-party districts and taking the voters out of the equation,” said former Representative Tom Davis, who led the House Republicans’ campaign arm during the 2001 redistricting cycle. “November becomes a constitutional formality.”

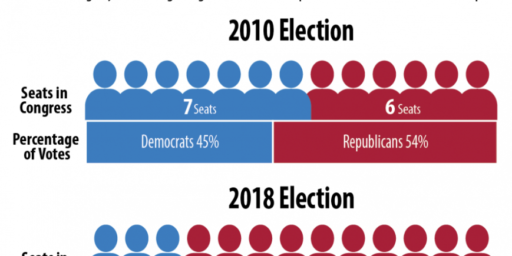

And note that the following is not a representative outcome, and it certainly is a proportional one:

Though Mr. Trump won 52 percent of the vote in Texas in 2020, Republicans are expected to win roughly 65 percent — 24 of the state’s 38 congressional seats. (Texas gained two seats in the reapportionment after the 2020 census.)

One of the reasons that I frequently balk at arguments that put political party messaging as the main problem with our politics is that I do not see, anywhere in our election processes, wherein there is anything that resembles a real test of what people want linking to electoral outcomes.

The U.S. House of Representatives isn’t representative as it pertains to the partisan preferences of the citizens of the 50 states. Hence it is difficult to say, one way or another if the problem is one of party messages.

We lack any kind of formal electoral mechanism to actually know what the public wants, even in the broadest of senses (recognizing that “knowing what the public wants” in any specific way can be very difficult). But if there is no mass-level competition for votes that accurately reflects something as relatively straightforward as the partisan preferences of voters in the states then we really do not have a representative democracy.

Put another way: how much do voters matter in our system versus how much do certain imaginary lines matter?

The most significant problem isn’t safe seats by themselves but the the lack of incentive to horse-trade. No Republican will back anything significant proposed by a democrat, full stop. And safe seats exacerbate the problem by giving more and more power to the true believers.

One longer term cure for this is that the true believers get more and more extreme and when they finally go too far and voters start to turn on them, they cannot recover. Witness California Republicans. Now that they are essentially NPC’s in California politics, horse trading has returned, albeit totally within the Democratic Party.

Concise, incisive, and true. But I don’t seem to be able to upvote an OP. Is there any organization actively pushing for multi seat districts?

@MarkedMan:

The lack of horse trading between parties goes back to the fact that the real election for a district’s seat is held in the primary. Primary voters are typically the hyper partisans and would oppose compromise. A representative in a safe seat has no incentive to engage the opposing party. Until there are competitive districts there will won’t be an incentive.

Looking at state level intra-party negotiations isn’t applicable to the federal government. There will be no time when Washington is dominated by one party in the manner of CA, TX or MA. So unless there is reason for congress critters to seek compromise, little or nothing will be done to address the nation’s issues.

@MarkedMan: +100 for correct usage of “NPC”.