Hurricane Irene And The Broken Window Fallacy

Repeating the "destruction creates wealth" fallacy every time there's a natural disaster doesn't make it any less of a fallacy.

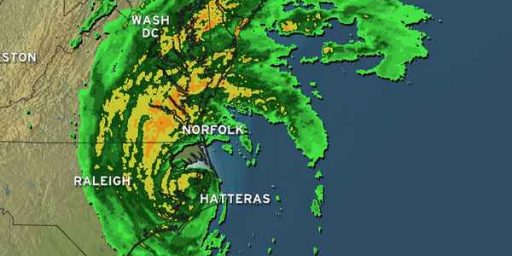

I knew someone somewhere would make the argument that the destruction caused by Hurricane Irene, which was thankfully much less than feared, but I didn’t expect it to come from Politico’s Princeton and Columbia educated “economics reporter” who picked up the ball usually carried by Paul Krugman in these matters:

The power outages and shuttered airports may stop the engines of commerce for several days, but Hurricane Irene might have provided some short-term economic stimulus as billions of dollarswill likely be spent to repair the damage to the East Coast over the weekend.

Cumberland Advisors Chairman David Kotok saw the storm as likely jolting employment in construction, an industry paralyzed by the bursting of the real estate bubble in 2008.

“We are now upping our estimate of fourth-quarter GDP in the U.S. economy,” he said in an email Sunday. “Billions will be spent on rebuilding and recovery. That will put some people back to work, at least temporarily.”

Kotok expects GDP growth — which limped along at less than a percentage point for the first half of the year — to exceed 2 percent in the last three months of the year and potentially reach 3 percent.

Mark Merritt, president of crisis-management consulting firm Witt Associates, said the hurricane should provide a bump in economic activity over the next few months.

“After a disaster, there’s always a definite short-term increase,” Merritt said. “There will be furniture bought, homes repaired, new carpet, new flooring, all the things affected by flooding.”

(…)

University of Maryland economist Peter Morici estimates that property damages will total about $20 billion, with another $11 billion in lost net consumer spending. Any economic impact of the hurricane should be negligible over the next five years, he said.

In terms of recovering from the storm, Morici said there could be some economic growth at the end of this year and the beginning of next year, because with the rebuilding, “largely what we’re going to get is a private-sector stimulus package.”

We’ve seen this argument before, of course, and it’s no more logical when applied here than when Paul Krugman applied it the September 11th attacks, World War Two, or a hypothetical alien invasion. As economist Sandy Ikeda pointed out when writing about a similar argument made in the wake of the Haiti earthquake, the illogic of the fallacy becomes apparent when you take it to its logical conclusion:

This is the same “logic” behind the notion that the bombing of great cities to rubble during World War II was good for economic development because it was an opportunity to construct modern infrastructure that would have otherwise required many years to put in place. Heaven forbid that we should have to wait for economic depreciation and normal wear-and-tear! (It was, however, good for New York, which had the great fortune of being the only major western city left standing after the war, but that of course was because New York itself was not air-bombed.)

The fallacy becomes clear when, by logical extension, one ought then to recommend deliberately making our cities vulnerable to natural disasters, by perhaps refusing to build sea walls and tremor-resistant structures. Why wait for disasters? We should invite them! Why waste resources on homeland security when just one well-placed nuclear bomb could boost our own economy, perhaps by as much as 0.3 percent? Think of the jobs! If you’re not into bombs, then how about advocating a new wave of 1960s-style “urban renewal” by unleashing an army of federal bulldozers onto our major urban areas?

What this argument ignores, and what people like Krguman and this Politico reporter refuse to recognize is the simple fact that destruction does not create wealth. The money that will be spent to rebuild, repair, and recover from Irene will doubtless line the pockets of the various contractors that will be hired to perform said work, but to argue that it “creates wealth” is simply a fallacy. By some estimations, the losses from Hurricane Katrina will total in the tens of billions of dollars. That’s wealth that doesn’t exist anymore, it’s gone. The money that will be will be used to pay for the recovery already exists and, rather than being invested in other projects, it will go toward repairing the damage caused by natural disaster. A home damaged by Hurricane Irene will be no more valuable after it is repaired than it was the day before the storm hit, for example. And this analysis doesn’t even take into account the losses from lower consumer spending that businesses will feel as a result of the storm, all of which will reverberate out into the economy as a whole.

David Boaz reaches back to Frederic Bastiat to put the final nail in the coffin on this one:

s Frederic Bastiat explained the “broken window fallacy,” a boy breaks a shop window. Villagers gather around and deplore the boy’s vandalism. But then one of the more sophisticated townspeople, perhaps one who has been to college and read Keynes, says, “Maybe the boy isn’t so destructive after all. Now the shopkeeper will have to buy a new window. The glassmaker will then have money to buy a table. The furniture maker will be able to hire an assistant or buy a new suit. And so on. The boy has actually benefited our town!”

But as Bastiat noted, “Your theory stops at what is seen. It does not take account of what is not seen.” If the shopkeeper has to buy a new window, then he can’t hire a delivery boy or buy a new suit. Money is shuffled around, but it isn’t created. And indeed, wealth has been destroyed. The village now has one less window than it did, and it must spend resources to get back to the position it was in before the window broke. As Bastiat said, “Society loses the value of objects unnecessarily destroyed.”

It’s understandable that people who learned their economics from professors who believe that you can create something out of nothing, and who don’t even seem to recognize the crucial role of private investment in creating wealth, would fall for a fallacy like this. That doesn’t make it any more untrue, though.

Doug, I’m no fan of Krugman, but to be fair to his argument, only 1/2 of his reasoning involved the broken window fallacy. The other half involved the potential for a post 9/11 Keynesian stimulus, which theoretically can work during a recession. I don’t remember Krugman making the same argument during the boom years.

To apply Krugman’s logic to our current situation requires that we acknowledge that Bastiat’s analogy was meant to be applied to a normal economy, not a recession economy.

Anyway, when it comes to the comments made by politicians in the aftermath of disasters (“I’m creating jobs by rebuilding our destroyed community”), I totally agree. I just think that the arguments by Krugman and other economists are not so easily dismissed.

You are confusing stocks (wealth) and flows (roughly, GDP or income).

Breaking a window — or damage from an earthquake or hurricane — obviously reduces wealth. However, the need to repair that damage may stimulate economic activity if there is productive capacity sitting idle (which there certainly is now, with unemployment over 9%).

That doesn’t mean that, on net, it’s better for the nation’s economy for people to go around breaking windows. Accordingly, no one is arguing that doing so “creates wealth,” your use of quotation marks notwithstanding.

Bleh. I swear that stuff is getting more stupid by the minute. This “I know Bastiat” meme seems to be quickly replacing horn-rimmed glasses as a sure sign of people who deem themselves better educated than the rest of the world.

Let’s see

This is of course completely correct. The economic benefit will be immediate while the losses are in future consumption. Does the rest of the quoted text contradicts this?

In short: in the attempt to demonstrate your superior insight over those “Princeton and Columbia educated” economists all you show is a lack of reading skills. You are effectively arguing against the voices in your head telling you what someone “who learned their economics from professors who believe that you can create something out of nothing” should be thinking.

(BTW where are they hiding those people??? I still have to meet that famous leftist economist conservatives base their idea of liberal education on.)

And Steven L. Taylor has already explained why you were misreading Krugmann on the aliens here.

Shorter Doug:

The money sitting in American banks was doing a great job funding a booming economy prior to hurricane Irene.

@ponce:

Simply brilliant! sarc/

Wouldn’t Bastiat only apply if it was the case that the persons who had the damage had to pay for said repair?

However, there will be insurance monies that will be dispersed and federal and state aid monies spent, not just out of pocket expenses (although there will be some of those, too). Yes, that money has to come from somewhere, but it is new money to, say, the construction economy of the damaged cities. Hence, there will be a short term stimulus as mentioned in the articles quoted.

The point of Bastiat is that the guy with the broken window has to pay the costs, and therefore cannot spend that money on other things. All well and good, but that is not the dynamic that we are talking about here. There will be new monies coming into the local economies to pay for cleanup, construction, etc.

Now, yes, much of said monies will be obtained via deficit financing, and that has its own problems (but they are not the ones Bastiat is talking about).

To put it simply: there are going to be construction workers and others who were unemployed before Irene who are going to have jobs, at least for a while (with the commensurate economic effects that said employment will create). Hence, “some short-term economic stimulus as billions of dollars will likely be spent to repair the damage to the East Coast over the weekend.”

I think it’s true that there is no increase in national wealth due to disasters, but there are REGIONAL improvements to infrastructure that are typically upgraded after a disaster.

Matthew Yglesias: The Denial Of Money [ed. or Fiat Lux]

I think the broken window fallacy is a good general reminder of the need to avoid “robbing Peter to pay Paul.” But is there not a mind-boggling amount of money simply being warehoused now because banks aren’t able or willing to put it into circulation? If so, then I don’t the that the BWF applies since capital injections will have come from essentially idle capital.

OTOH: the warehoused money is borrowed money, so it has been prospectively taken out of the economy already, even if it is the national economy of future years rather than the present. So the completion of the BWF cycle gets done down the decade instead of now. Yes? No?

Second, is there a financial equivalent of the 2d law of thermodynamics (no free energy)? Meaning, is the monetary value of what is destroyed greater than the value of the economic activity to be engendered to deal with it? It would be interesting to see an economist assess this, especially factoring in the taxes that local, state and the federal government will siphon off the transactions, which will actually reduce the value of the total economic activity.

I’m not an economist, these thoughts are off the top of my head.

Those trying to find excuses for the benefits of breaking things need to learn to accept one thing: Its not about economc growth. If you want to accuse Doug of something, it is the utilization of a false metric. Krugman doesn’t care about economic growth, he cares about unemployment and the depreciation of human capitol that results from it. He is willing to make the trade-off of employment for growth, but since most people with jobs or dependent on retirement entitltements are scared sh!t^@$$ by the implications of a future of low or non-growth, the trick is to keep the attention elsewhere.

@PD Shaw: High unemployment inhibits economic growth, so yes Krugman does care about GDP. The economy will not recover until the country deleverages, so unless you’re willing to endorse debt jubilee people have to get their jobs back and start seeing wage growth for the first time in thirty years. A consumer economy does not grow unless the people consume.

Doug must post his broken window things and move on. He must not even read comments, because if he did then he’d already know the difference between a short term argument about spending and a long term argument about wealth.

Congrats to those of you who explained it all again, you have more patience than I.

Of course, if we get another BWF post, misapplied, in a week or two, we’ll know it was for naught.

(Near as I can figure, PD rejects Krugman’s liquidity trap, and the judges Krugman as if Krugman himself does not believe in the liquidity trap. That’s not really fair. To understand Krugman you have to at least accept that Krugman is thinking in the liquidity trap framework. For Krugman, to get growth, you have to break the trap.)

@Ben Wolf:

What’s the definition of jubilee this week? Is it forgiveness of all debt, or just forgiveness of bad debt?

(Neither is possible, without discarding our entire system of finance, I’m just curious.)

@john personna: I’ve given exactly one example of a possible debt jubilee. Your response was to become verbally abusive. Feel free to list the “definitions” you claim I’ve posted.

It also seems odd that’s the part of the sentence you focus on when the reference to jubilee wasn’t the subject. You don’t understand macroeconomics, you don’t understand the relationship between monetary and fiscal policy with debt and you don’t understand what a balance sheet recession is. I’ve only used the term fifty times, and the fact you haven’t bothered once to understand it illustrates why we’re in an economic mess.

@john personna:

You know, I’ve given you these before. Your ability to forget them doesn’t speak well for your sanity. In August 23, 2011 at 18:46 you wrote:

But in August 24, 2011 at 17:09 you wrote:

Which is why I asked you above which it was, the August 23 version, or the August 24 version. One is all private sector debt, and one is just non-performing debt.

Now, on your smear-paragraph, I’d say it is typical of nuts to think they are that far inside someone else’s head.

If this wasn’t a fallacy, the earthquake in Japan should be energizing the world economy, but even Barack Obama has used the earthquake as an excuse for a less than robust economy.

Doug, is it possible that the people you are citing here are “trying to make lemonade” rather than advocating for the value of breaking windows? Must everything in your world be an attack on capital? Give it a rest. Go back to lawyering for a while; this is wearing on you too much.

@john personna: And you’ve again demonstrated a somewhat startling aversion to reading. Note what my comment was in response to:

In both comments you list debt forgiveness was discussed in the context of individuals with underwater mortgages.

And you again resort to name-calling. I’ve been nothing but polite to you sir.

So which was it above, are you asking PD to “endorse” the full “forgiveness” of private debt? “All $50 trillion of it?”

That would be an international debt, right?

@john personna: I didn’t ask him to endorse anything. I stated that unless he wants to go the debt relief route, reducing unemployment and restarting wage growth are the only other means by which the private sector can deleverage in a balance sheet recession. If we don’t take action one way or another we risk a deflationary spiral that could take decades to climb out of.

Nor did I intend to give the impression all $50 trillion must be forgiven, I simply listed the total amount of domestic private debt to emphasize how serious the situation is and recommend a complete and total debt forgiveness program for people who are underwater due to loss of home equity. Everyone gets in, no exceptions or lists of qualifications to jump through.

You do understand there is only one way for the private sector to save while increasing net financial and real assets, yes?

I encourage everyone to take a look at this:

http://www.debtdeflation.com/blogs/2010/09/20/deleveraging-with-a-twist/

The tremendous private debt level is the primary issue with the U.S. economy. While our “leaders” in government and business fiddle with non-economically relevant public debt, the consequences of the private sector credit bubble are crushing the country.

Yes, their will be an increase in spending in the local area via insurance payments, government payments, and private savings. Of course, in the big picture, those fund will no longer be pooled for investment so there will be a decline in investments in productive enterprises. The funds, instead, being used to repair and restore existing infrastructure or, in the case of government funds, not being borrowed.

Of course, some here feel that the rightful owners of those funds weren’t using them in the manner most productive for the collective. But if they were working on pulling together the capital for an investment that would have resulted in hiring, that will now be cancelled or delayed as billions of dollars are provided to pay for things that already existed.

I do love how so many can’t seem to understand that if the FED or government just prints money, what happens is that the price of goods and services increases so that the same amount of goods or services is purchased. Whether a fiat currency or one backed by a standard commodity, it still only buys a fixed quantity of needed resources whose price will increase relative to the debasement of that currency.

@Ben Wolf:

Your August 23 post seemed a strong endorsement of real jubilee. I don’t think real jubilee is remotely possible, nor is anything remotely worthy of the name. If you are talking, for instance, about remediation for some limited set of home loans, it’s better to drop that name altogether. For “jubilee” to mean anything it has to mean … what it means. That is a universal debt-forgiveness across society.

Now, you never really did ask me if I thought this was a balance sheet recession. I actually think that’s a fair way to describe part of it, but not all of it. If you look at it that way alone, you might think that unemployment is all cyclical, and that jobs will come back when the balance sheets are repaired.

It’s worse than that, because it was a debt crisis powered by global imbalances which have not themselves gone away.

This isn’t necessarily true. Printing additional money can lead to inflation if it leads to an increase in aggregate demand. But we are currently experiencing low demand; so low the economy is stagnating. The appropriate action would be for the feds to pursue a countercyclical monetary policy.

I remember my grandfather lamenting ad nauseam how greatly prices had changed since he was a boy. “A bottle of coca-cola was a nickel”, he would say. When I asked him how often he drank coca-cola, he said his family could only afford a few bottles per week. What he hadn’t considered was that now (or at the time) a bottle of coke may have come to cost over a dollar, twenty times what he paid for it as a child, he afford to buy far more than twenty time as much. The individual dollar had declined in purchasing power, but the number of dollars hed had access to had grown more quickly and his wealth had therefore increased. This is how a healthy economy works.

You’re assuming that the economy is always operating at capacity. To be sure, if the economy is operating at 100% of capacity, the person who repairs a broken window has to stop working on something else. But if not, not.

The question here is what effect storm damage, etc., will in fact have on the economy, not whether it’s fair or unfair or whether you or I happen to like it.

@alkali:

No, my point was that the money that will be spent to make those repairs was being utilized elsewhere in the economy, more likely in the advancement of productivity rather than rebuilding infrastructure long before it’s life cycle warranted replacement. Or is it your contention that the insurance payouts, government grants and personal savings just miraculously appear out of thin air and were not and could not be otherwise utilized to grow the economy? Instead they are being used to replace capital stock that until damaged had useful life remaining.

But there will be churning and a redistribution of wealth due to the storm. But no growth as few will invest in the hopes of more damaging storms regardless of how much plywood, how many couches or carpets are purchased in this blip.

@JKB:

Remember, $9T are being held in treasuries. Even paying ~0% interest doesn’t stop them from buying. And as I understand it, a good part of that $9T is corporate cash. Short term treasuries are used as liquid money.

I get what you are saying, but I think the reasonable observation is that “crowding” in all its forms is not always equal, and opportunity cost varies.

@JKB:

Put another way, your argument would be best if you could show that companies were heavily invested right now, and short cash.

It’s an important premise of the argument that the economy is not operating at capacity. As a factual matter, corporations are indeed sitting on cash, and there are substantial numbers of unemployed people and idle capital resources. It is reasonable to expect that some of those resources sitting idle will be put to work to repair the storm damage.

You challenge me to deny that those resources “were not and could not be otherwise utilized.” The difference between “were not” and “could not” is the entire point here. Certainly idle resources could be otherwise utilized. The point is that they are not being otherwise utilized. That is why the economists that DM quotes predict that the repair work will stimulate economic activity in the coming months, as idle resources are put back to work.

BTW, I like this essay at The Economist for the muddled confusion and understanding it shows about sources of wealth and the nature of investment.

Should I sit down at my vice and tie some Adams dry flies today, or should I order some over the internets? Which creates more wealth? (We can never know.)

JKB, the “crowding out” meme is an illusion in terms of government spending. In fact the exact opposite occurs when the feds engage in deficit spending: new money is created and then transferred to the private sector. Crowding out occurs when governments run surpluses, which by definition pulls financial assets out of the private sector and limits the accumulation of wealth.

It’s a theory in search of supporting evidence: if crowding out is a reality, why aren’t we seeing it now? Neo-classicists were adamant the stimulus would spike interest rates, which actually fell. Nor has Japan experienced crowding out in twenty years of government deficit spending. There is no empirical evidence the effect exists.

This has nothing to do with “crowding out”. What it has to do with is that money that could have been spent to create new productive facilities is now being used to restore old, established infrastructure. This activity does cause a stimulus to the idle construction and household goods industries. However, the economy as a whole is no better off as the money to pay for those goods and services are no longer available for other use.

Deficit spending does not create “new money”. It is a claim against future tax receipts. A claim, if you’ve been paying attention, that is becoming so large as to require painful spending cuts and probably economy crushing taxes. This does help explain why Progressives can’t comprehend the deficit and the debt limit problem.

At some point, when things become so desperate that even Obama and the Progressives will have to adopt rational and reasonable across the board policies and actions to induce the private sector to again feel confident to make productive investments and hire, interest rates will rise perhaps precipitously to try to dampen the inflationary overhang of the recent flooding of the economy with the illusion of cash.

I considered responding to Doug Mataconis’ argument, but I see a number of commenters have done so, and quite effectively. Mataconis is recycling a question he raised on 8/15. Given that he’s a lawyer, we probably should have simply responded ‘asked, and answered’.

The more interesting discussion would be – why is it so hard for many people to understand the rather unremarkable proposition that, given a labor surplus, repairing damage can create employment, at least in the short term? Is it a deontological refusal to recognize that a given thing may have one effect in a time of labor and capital scarcity and a different effect now? Is it a belief that capital is too limited now? Is it a simplistic ‘destruction is bad, nothing good can come from bad’? Is it some sort of sunk money fallacy, that we already paid for the bridge so repairing it doesn’t count? Is it a belief that Is it that the right wing echo chamber has declared stimulus bad and that’s the end of the story? What?

(That repairing damage can generate employment, incidentally, was not Krugman’s point, but that was adequately thrashed out following Doug’s 8/15 post.)

@JKB:

You are arguing against a position no one is taking (“new money”) and ignoring the one actually being made (“liquidity trap”).

But you see, you have a catch-22 there. You want government to take action by inaction, and you want this inaction to inspire.

If that worked, it would have stimulated real Bush recoveries, 2000-2008.

@gVOR08:

IMO I think it is a desire to argue against the idea of government stimulus in general or a wish to deny the notion that government can actual engage in spending that has a net positive effect (indeed, I think a lot of the arguments about deficits in general as less about concerns about future generations but rather just general unhappiness with government spending qua government spending).

Bastiat’s BWF seems to be a current favorite as an example of why things like infrastructure spending are a bad idea. (The funny thing is, the BWF is not about government spending).

@Steven L. Taylor: It’s particularly interesting because the question posed here — will the need to repair hurricane damage stimulate economic activity? — on its face has nothing to do with government action. (As it happens, the government may expend some money on repairing hurricane damage, but the question is answerable even if the government does nothing.)

This is utterly false. The federal government is the monopoly issuer in the United States. There is no other entity which can create money. Nor is spending a claim against future tax receipts. The government doesn’t go check the till before it spends, it simply credits accounts. In other words it spends money into the economy. You keep thinking in terms of the gold standard, where government had a finite supply of gold and therefore (in theory) a finite supply of money. In our current system government “manufactures” money. It then transfers those assets to the private sector by spending.

You might ask why the government doesn’t just spend on everything without bothering to tax at all, and the reason is inflation. That’s the break on what government can do, not an arbitrary amount of debt which only functions to control interest rates anyway. The bonds we issue are otherwise meaningless and are not in reality set against future tax receipts. Taxes are for an entirely different purpose than funding federal spending.

@Ben Wolf:

I’ve heard that definition of spending and tax before, as alternate metaphor, but never as the only reality.

It is also valid to call debt “future tax” (with caveats about inflation, the value of future dollars, and debt to future GDP.).

OMFG…not this again, I think we have like…5 of these posts now. JFCOAFPS.

It is simple…

We have wealth W. We lose a*W. Now we replace a*W. If welfare is a result of wealth, the loss is a reduction in welfare–i.e. we are made worse off. The replacement returns us to the status quo–i.e. there are no welfare gains.

If there is slack capacity there might be some reductions in unemployment (broadly defined–i.e. labor and other resources).

However, this is again, not a net gain because the wages paid to those unemployed resources are part of the replacement of a*W.

In the end, we wont go around randomly bombing buildings and such to try and improve our economy. The destruction of wealth (which by the f*cking way the housing crisis did a way f*cking better job than Irene) is not a recipe for success.

JFCOAFPS and FMIBE, now, can we f*cking stop?

Ben Wolf,

No. Fractional reserve banking. The Fed (or other central banks) can create a given amount of money, but fractional reserve requirements allows commercial banks to create additional money as well.

Fiscal (deficit) spending and the creation of money is not uncontroversial. The government is not spending simply by creating new money, but by issuing TBills which earn interest–i.e. they borrow. However, different schools of economic thought have different views on the impact of such borrowing, some views (e.g. Austrian) hold that such borrowing will lead to more money and thus inflation when you have a fiat money system.

Keynes must have been a bad economist for realizing we were far from full employment in the 1930’s. And I guess good economists are those who look at the US economy and asks what GDP gap?

@Steve Verdon:

I don’t think anyone here has disagreed that damage is a wealth reduction.

I think we are disagreeing with the construction “since there is a net, long term, wealth reduction, there is no short term stimulus either.”

I would not be so mean to knock down your house, and stimulate you into a rent-or-buy search, not because it would not be stimulative, but because of the long term cost.

Maybe we wouldn’t have an N-th iteration of this thread if the BWF were not misapplied in short-term analysis.

John,

If that is the case, a short term stimulus, how come the housing crisis was not a stimulus? I would argue that a wealth reduction tends to be more associated with a reduction in economic activity not a stimulus. That a government can borrow and spend money to try and return to the initial level of wealth does not make it clear that there is, on net, a stimulus effect.

In short it is a highly debatable position, and given the long term costs maybe we should just stop this kind of nonsense. Keep in mind that the stimulus position depends on slack capacity, so at the very least it is special case proposition and one I see no theoretical reason to believe holds in all cases. Here let me be very simple (I hope) and specific:

(1) Wealth destruction causes a decrease in private economic activity.

(2) Government response cause an increase in economic activity.

That (2) > (1) in all cases when there is slack capacity has not been proven in this thread. That is the best you can hope for: that nasty destructive event during a time of recession, if the government responds well we might, if we are lucky, get a bit of a bump in employment. Maybe. Of course, we’ll have the long term consequences to deal with, but hey gotta find the silver lining somewhere.

@Steve Verdon:

The housing crisis was a pinnacle of oversupply, not destruction of existing stock.

Interestingly, I just read that Mark Cuban is down with tearing down that oversupply. I wouldn’t go that far.