Institutions Matter: Just Look at the Congress

Representative democracy is a process of delegation of power to agents who act on behalf of citizens. The process of delegation matters.

Doug Mataconis is correct: to understand congressional behavior, especially within the Republican Party at the moment, the issue is not a case or irrationality, but of fairly typical behavior for politicians. That is: the main motivating factor in their decision-making is driven by the desire to be re-elected and the parameters for that re-election are driven by the institutional parameters that structure a given re-election process.

Doug Mataconis is correct: to understand congressional behavior, especially within the Republican Party at the moment, the issue is not a case or irrationality, but of fairly typical behavior for politicians. That is: the main motivating factor in their decision-making is driven by the desire to be re-elected and the parameters for that re-election are driven by the institutional parameters that structure a given re-election process.

The basic theory behind representative democracy starts with the premise that power resides with the citizens and that the citizens cannot govern directly because there are too many citizens to assemble in one place (and because, quite frankly, most citizens lack the time and inclination to bother with the work of government) and so, therefore, citizens delegate their power to govern to agents who govern on their behalf for a set amount of time via the electoral process.*

The way this delegation process functions is vital to the ultimate functioning of the overall mechanism and eventually determines how good of a job the government does in actually representing the diverse interests of the citizens. Further, the delegation process itself can create problematic, imperfect, and/or perverse incentives in terms of how these agents behave once elected (e.g., being willing to crash the economy over raising the debt ceiling for spending that has already been legislatively approved or refusing to vote for any tax increase of any kind no matter what).

There are a variety of ways that our current system creates real problems in terms of delegation of governing power to agents from the people (at least if what one presupposes the role of representative democracy to be to the furtherance, through deliberation and compromise, of actually governing). The debt ceiling debate of recent vintage and now the so-called fiscal cliff discussion underscores this problem (as does, really, the overall situation with the deficit, and therefore the national debt).

A national legislature is the most important institution in a representative democracy since it is the body that, at least in theory, assembles direct representatives of the population in one spot to make authoritative decisions for the country as as a whole. Since opinions and interests are diverse, we would expect that compromise would be needed, and that specific interests in society would often be disappointed by the outcome of the legislative process. We would, however, ultimately expect that some sort of outcome would be produced, and that it would be one that was reflective in some significant manner with the national sentiment on an issue. While this might, for example, lead to poor decisions at times, or to can-kicking, it is assumed that the system would produce adequate public policy so as to keep the government functional.

However, it has increasingly been the case of late that Congress has been incapable of delivering on this rather low level of expectation. Consider the lack of budgets passed in recent years as well the way the debt ceiling crisis was handled (by kicking the can) and the way any number of issues has culminated in the current mess. These are not the behaviors of a well functioning legislature. Part of this is because of the design of our system (bicameralism with co-equal chambers coupled with a president who holds a near-absolute veto). As such, there are reasons to expect slowness and even impasse. But, and this is rather important, there are other features of our system that create further difficulties (if, at least, one actually wants a system that attempts to represent the actually interests of the citizenry and that allows for adequate governance). The filibuster as it has evolved is such a feature, but lets think about elections.

First, the single-seat district, plurality electoral system that we employ tends to narrow choices and creates easily-manipulated outcomes. It is really important to understand that the US, as one of the very first attempts at representative democracy, had very little in the way of examples to draw from for its set of institutional options and this was especially true of electoral systems. So, we went with a very simply system that became so firmly rooted that we never talk of altering it (save very much on the edges like California’s Top Two system). The only model we had, really, was the single-seat constituency model in the UK used to elect the Commons. However, if a country was writing (or rewriting) a constitution (or just its electoral laws) today, the odds are exceptionally high that such a system would not even be considered (and, indeed, this is what we have seen since the late 19th Century). There are multiple reasons to make this claim, but his post is already longer than many may wish to tolerate, so I will forego a discussion of options and why they are superior, but will note that we lack any debate whatsoever on this topic, which is (I would argue) partially because we are simply unaware that any other options exists. (Let’s face facts: we are not, as a population, all that well versed on how our own system of government actually functions, and are wholly ignorant of the systems in other countries).

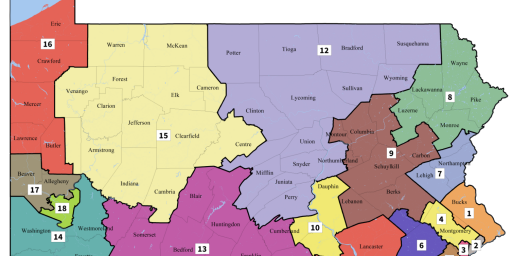

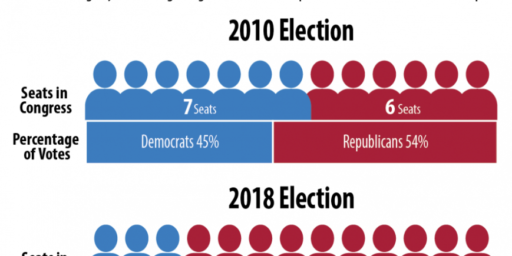

The bottom line is that a system such as ours tends to create two large, catch-all parties they tend to dominate politics (although the US case is the most so-dominated—the UK, for example, has two large parties but has viable third parties, and India has a multi-party system, to name two examples). Worse, however, is that our system makes it ridiculously easy to manipulate district boundaries, and to to so in a way that guarantees a given party will win a given district. Partisan gerrymandering, as Doug’s post noted, has increasingly made things like actual electoral competition on elections day a quaint notion in the vast majority of House districts. (I would argue that the vast majority of people do not know or understand how little election day matters for the House).

This is not good. It is not democratic, nor is it adequately representative. It certainly short-circuits the main theoretical basis of the legislature. While gerrymandering is an old concept (it is named, after all, for one of the Framers: Elbridge Gerry who pioneered partisan district drawing in Massachusetts), the process has become increasingly sophisticated (computers make it a breeze) and partisan (since in most states the legislatures draw the districts). This has taken large helpings of competition out of our politics. Consider that for a bit.

A second issue is the party primary for nominations. While on the one hand, this seems to be an especially democratic way to name candidates (and the process was designed to take the power of nomination out of the hands of party bosses), on the other the nature of the process is such that it actually can be said to damage the overall representational nature of our system.

Consider: if one lives in a safe Republican district, then the Republican nominee is going to win election in a given general election. It does not matter if the district, as a whole, is moderate, conservative, or very conservative in its orientation, the Republican will win. Certainly there will be no real competition with the Democratic candidate.

The selectorate that is created by the primary process is not representative of the district as a whole, nor is it even necessarily representative of the Republicans in that district. What we end up with, therefore, is a system that does a really lousy job of picking representative representatives.

So, the basic institutional logic flows like this:

1. Single seat districts require the winning of large numbers of votes to win a seat, which increased the odds that large parties will form and win seats.

2. Single seat districts can be relatively easily drawn in a way that favors one party over the others. (And since our system is dominated by partisan actors having the power to draw districts, the districts tend to drawn in a partisan fashion).

3. Primary elections mean that a sliver of the favored party in a given district will select the nominee, and hence the eventual winner, of the district. (Remember, too: not only is the primary winner chosen by a subset of the partisan identifiers in a district, but that turnout for primaries is quite small relative even to low-turnout general elections. This empowers relatively small, and often ideologically distinct, subsets of voters**). Congress, therefore, gets selected not by “the people” in any subtantive way, but by a subset of a subset of a subset.

Hence: a given member of Congress does not seek to represent the district as a whole, or even his or her co-partisans. Rather, a given member of Congress seeks to represent the primary selectorate that holds the power to re-nominate that Representative, which is that Representative’s return ticket to Washington. If the selectorate in question hews heavily to the Grover Norquist view of the universe, even if that is to the detriment of the district, well c’est la vie.

When we consider all of this, it underscores why Doug is correct: rational actors acting rationally under these rules leads us to stiff like the fiscal cliff.

Worse, however, is that the institutional logic of this set of rules and processes does not come close to the basic theory of representative government I noted above. This is not a process the allows the citizens to have their view represented in the legislature where they can be debated and voted upon. No, this is a system that allows for small slices of existing parties to govern the whole of us. This is, to put it mildly, problematic.

We have a system currently in which congressional approval can hit the upper teens/low twenties and yet only 51 seats out of 435 are competitive on election night. If one values representative democracy at all, these numbers should be troubling.

There are ways, small and large, to start addressing these types of issues, but the first step, as they say, is admitting that there is a problem. And while we bemoan things like the fiscal cliff debate, we rarely actually talk about the system that produces such outcomes. We like to blame the players, but rather do we look at the game. It is time to start talking about these issues and stop pretending that just because we worship the Framers that everything that was put into place in their time was perfect. We are constantly upgrading the technology of our lives, yet we don’t even consider that the mechanisms of governing can likewise be tweaked. And, it should be noted, there are large and small tweaks that can be made, but that the bottom line is that we do not even have the basis for a serious conversation on the subject, and so no discussion ensues. It is easier, I guess, to make up crises with easy to recite names and just assume that if we had the right people in office that all would be fine.

The funny thing, by way of closing, about assuming that the right people would make the right choices is that the very logic of the Framers (and certainly of Madison in the Federalist Papers) was that institutions have to properly constructed for government to work properly and that they, therefore, would likely favor of rethinking institutions over time.

We tend to assume that a) the Framers set forth a perfect system uniquely suited to the US, and that b) the problems that exist are the result of the system not working as designed in some way. However, the truth is a combination of c) nothing is perfect, d) there is a host of comparative information that we could look at to consider various alternatives, large and small, and e) much doesn’t even work as intended anyway.

BTW: a more robust, properly functioning representative system does not guarantee good policy, but it does increase the odds. At a minimum, a truly representative body is a response body–something we currently lack.

*This is, by the way, not only the basic definition of “representative democracy” but also of “republican government” (i.e., a governmental system that derives its power from the mass of citizens, i.e., a system of popular sovereignty, rather than from a special class of persons imbued with the legal power to govern, i.e., an aristocratic system). Hence the reason that I frequently note that the notion that the US is “a republic, not a democracy” is nonsensical unless one means that we do not have a direct democracy where all citizens meet together to govern (but then again, who is claiming that?). For more on this see my post Madison’s Defintion(s) of Republic.

**This is, of course, what we see within the GOP in recent cycles.

Good read. This is year-ending worthy, so to say.

@Ryan M. Spires: Gracias!

Institutions matter. Elections matter. Policies matter. Legislation matters. Appointments matter. Nominations matter. It all matters. No question.

Political decisions have real world consequences. Ask people in Detroit. What’s left of them, that is. Chicago. Philadelphia. Ask the Greeks, Italians, Spaniards, hell, the rest of Europe. Former domestic steel workers. Former domestic textile workers. Former lumber sector workers. Former manufacturing sector workers. Victims of recidivist criminals. The unemployed in cities with “living wage” ordinances. People who can’t afford to pay rent in cities with strict “rent control” ordinances. Gunshot victims in cities with strict “gun control” ordinances. Affirmative action recipients who then flunk out because they’re not prepared nor qualified and who then wind up in worse shape. Ask all of the millions of people out there who are unemployed or underemployed, largely because of excessive regulations and taxation. Ask the people living on the dole up in Alaska, barely making ends meet, who’d rather be working for high wages and good benefits on oil rigs up in ANWR.

It goes on and on.

Perhaps the greatest irony is the media-academe-Internet cabal is incapable of connecting the true underlying political dots.

If at some point you have the time and energy to write it, I would love to read your explication of alternatives to the single-seat, plurality electoral system. I can only imagine it will be as interesting and enlightening as this post.

(Oh, and I’d like to thank the Tsar for highlighting just how intelligent Dr. Taylor’s post was by immediately following it with his standard illiterate gibberish…)

Good post. Obviously some time in gestation. Thank you. Hopefully it will lead to a good comment thread, including more from you.

Another great article.

The only point that can be added is that because States largely reproduce the current national representation system, the key challenges you laid out — gerrymandering and the primary system — are likewise reproduced at the State level. And since it’s the State Legislatures that oversee the drawing of district lines and the running of elections, we end up with local institutions that propagate and further entrench the problem.

All of this makes changing the system even more complex as any national change can only be accomplished through changes at the state level.

There’s something I’d like to present for consideration: that significantly more Congressional districts would lead both to greater legitimacy and decreased judicial tolerance for gerrymandered districts. Take the Illinois 4th Congressional District, for example. The reason that it withstood judicial challenge is that without it there wouldn’t be a single Chicago district with an Hispanic Congressman.

Today each Congressional representative represents nearly three quarters of a million people. In 1960 each Congressional representative represented fewer than a half million people. In 1910 each Congressional representative represented just over 200,000 people. When the Constitution was written the number of constituents per representative was envisioned at around 40,000. Some, like Washington, thought that was too many.

Even granting better transportation and communications than in 1790, I don’t think that anyone can reasonably doubt that three quarters of a million people is just too many for one representative to represent adequately.

@Dave Schuler: I absolutely agree: the House is too small given the size of our population. This is actually far more doable (though still difficult to accomplish) than broader reforms.

@wr: I do intend to do that. It may become a writing project for the New Year that could be worked out via blogging.

@gVOR08: Yes, much gestation! And more to come, I hope.

(Thanks to you both for the kind words).

@mattb: True: local politics functions very much like national politics in a lot of ways and creates some of the problems in question.

The only major difference at the local level is that partisans often have a far higher incentive, for a variety of reasons, to work together (which is why governors who run for the presidency talk about their record of bipartisanship at the state level–pretending as if they were the reason for the cooperation rather than acknowledging that often local dynamics simply encourage it far more than is in the case in DC).

@Dave Schuler:

Today each Congressional representative represents nearly three quarters of a million people. unless it’s one in a very low population state such as Wyoming or Alaska.

This is part of the problem to get representation at a ratio of 50k to 1 we would need a House with 6000 members. It has been my feeling that 50 states are too many and the borders make no sense. smaller states need to be consolidated and larger states need to be broken if only for the purpose of national representation. Of course that won’t happen.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Ummm… yes please! On multiple counts…

Not only would such a series of articles be a great feature for OTB, I suspect that a lot could be gained through this sort of writing process (with immediate feedback from our little peanut gallery) — especially if the result was intended for a more popular audience (versus a poli-sci journal).

@Steven L. Taylor:

Correct. Though when it comes to electoral issues it appears the two sides work together to protect the current two party (deadlock) status quo. So in New York State — for example — one party always retains control of one house and the other party owns the other house.

Just as a minor historical nitpick, in the late 18th century (and up to the late 19th) the most common model in the UK was a multiple seat constituency where the voters had as many votes as there were seats,with the top scoring candidates each getting a seat, so it wasn’t uncommon for a single constituency to return a variety of types of candidate.

Surprisingly the last 2 multimember constituencies lasted until 1950 (oxford and cambridge Universities…….where the voters were the graduates of the university no matter where they lived……)

@mattb:

Indeed.

@kenny: You’re correct: I was being a bit sloppy there.

Awesome article. Thanks.

It’s Duverger’s Law. It was inevitable that we’d have 2 dominant parties.

We have institutional flaws that are intrinsic to any winner take all system. But what are the other options? And are they really more representative? It’s hard to see how something like a proportional representation system with multiple parties would be more representative. Also, proportional representation is certainly far more prone to extremism than a two party system.

I don’t think this is the case. The winner of the elections will always be the person who appeals to the highest number of voters, and therefore the most representative. You cannot have a winner take all majority rule system and have a small “subset of a subset” determining the winner. It’s impossible. The primary candidate winner will be the most popular within the party, i.e. the most representative of the party, and the eventual winner will be the most popular in the district, i.e. the most representative. The fact that you have polarization is more than anything reflective of a deeply divided populace.

Also, how do you know the problems of gerrymandering is fundamental to our institutions, and not just a problem with the rules that govern redistricting?

@Rick DeMent:

Smaller Congressional districts would alleviate that problem, too. Let’s say that each representative were to represent roughly 100,000 people. That would mean a House with about 3,000 members and Wyoming would have five; Montana would have nine;California would have 380.

I think that’s an acceptable and manageable size. If you don’t think it is, I think it’s equivalent to saying that we’re too large for representative democracy.

…Shorter Dr. Taylor…

…the Republicans are stinkin’ up the joint.

…and well said I might add.

@Coop: Duverger’s Law is heavily reinforced by the primary system, in fact. Indeed, the Law really works best in the US, but does not have as stark an effect in the UK, Canada, nor in India.

This is how most people think about it, but it is not the case. You assertion assumes a) that all adherents of a given party vote in primaries (they do not), and b) that that the electorate is the same in the primary as in the general (it never is).

The bottom line is this: in a truly safe district the only contest that matters in the primary (because if you win the primary, you win the seat). Primaries have far lower turnout than the general, and the primary can be far more easily dominated by the base of the party/the ideologically committed. As such, the electorate that matters is the primary electorate in such a scenario, not the general election electorate.

@Dave Schuler:

Sure I could live with a 3000 seat house … it would be a lot more expensive to buy off that’s for sure. You might also get more parties involved, a lot more chance for third parties to compete and for coalitions and harder to reliably gerrymander.

@Steven L. Taylor:

No, because in the United States you have a Regional Coalitions that works as if they were parties(And in UK, Canada and India a vote for a MP is a vote to choose the Prime Minister, so, every election is a local election). One could argue that the Blue Dogs could be considered a party of it´s own, as the Boll Weevils and Rockefeller Republicans in the past. By the way, in Mexico and in Brazil you can see these regional coalitions at the work, but with parties that are pretty strong in some regions, but not in the others.

Part of the problem is precisely that: the American Democracy is designed to have weak and decentralized parties. On the other hand, the fact that there are so many national organizations giving money to local races is creating centralized and very strong parties. The Republican Party looks like to be the most dysfunctional of the two parties precisely because it´s the party where out of state and outside money has more influence. A Republican Congressman has to fear things like Club for Growth, Grover Norquist and Freedomworks, not his constituents.

And the American Political System was not designed to have parties so centralized at the National Level.

As such, the electorate that matters is the primary electorate in such a scenario, not the general election electorate.

When I was growing up in Kentucky the vast majority of local elections had no GOP candidates and the primary did decide who won the election (I had moved away from home when they elected the first Republican for mayor back in the 90’s).

The Republican Party looks like to be the most dysfunctional of the two parties precisely because it´s the party where out of state and outside money has more influence.

There is no group with more influence and money to burn than unions and they aren’t supporting the GOP.

@Just Me:

That’s a joke, right?

@bk:

Holy crap, there now IS evidence of a mirror parallel universe, because Just Me must be posting from there.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Just want to add my thanks to you for this post, and am looking forward to your followup post.

If the House goes to 3000 seats, should the Senate remain at 100? (I know change would require a constitutional amendment.)

A 3000 seat House sounds like a full employment program for politicians, lobbyists, and political consultants:-).

@Steven L. Taylor: Dr. Taylor, you are absolutely correct. I live in a totally safe R district district where the newly elected state rep was fired from the local PD for falsifying his on-duty time and also had declared personal bankruptcy. He’s in and will probably go on to higher offices.

@Just Me: “There is no group with more influence and money to burn than unions and they aren’t supporting the GOP.”

How about staying in the same universe as the rest of us?

The AFL-CIO, NEA, AFT, SEIU have plenty of influence inside the Democrat Party, but things like Club for Growth, FreedomWorks, Crossroads GPS, etc have an even bigger influence inside the GOP. There is no equivalent to the Blue Dogs on the GOP, and the GOP Primaries are more nationalized than Democrat Primaries.

Although these defects in the system help the GOP and the Tea Party in the short run at the House level,the House representatives elected from these gerrymandered districts are going to have a hard time making the jump to statewide offices, unless the state itself is solidly red. See Akin, Todd.

Also too, the fall of Allan West and the return of Alan Grayson points out the limits as to what gerrymandering can do.

@Andre Kenji:

Odd. I am unaware of a “Democrat Party.” Perhaps you mean the Democratic Party?

@Just Me: Where are you posting from, the 1950s?

@stonetools:

In the case of West, the reason he lost was primarily due to redistricting. Ditto a number of the darlings of the far right who went down this cycle — and a few of the more “left” members of Congress.

As far as Todd Akin, Missouri is a reliably Red state. And McCaskill should have lost — or most likely would have lost if anyone else had run. What saved her was the Republican primary and the fact that the top two picks split the vote allowing Akin to get the victory.

Now all that said, its more interesting to look at the case of Richard Murdoch in Indiana or Christine O’Donnell in Delaware for examples of insurgent “far right” candidates who tanked at the state level.

@stonetools:

No, because lobbying would require lobbying dozens of Congressmen at the same time and campaigns would be cheaper. A three or even a single neighborhood in Chicago or in New York could have it´s own district – Chinatown in NY, for instance. Managing a campaign is such a small area would be pretty easy and cheap.

@mattb (as in the pro-gun regulation matt):

That’s interesting.In Florida, it was the Republicans would who did redistricting after 2010. How come they didn’t protect their Tea Party darling and keep out Grayson -a prime object of conservative hate?

Harry Reid wrote the playbook on how to deal with these conservative candidates in a state wide race. First, you try to influence the choice of candidate by supporting the most conservative choice. Once that choice is in, you beat them over the head with their most radical positions until electorate clearly understands that what they are getting is a conservative radical. You don’t let them get away with pretending to be centrist. Reid created the template and McCaskill, and to a certain extent Murdoch and Obama followed it. What McCaskill and Murdoch proved is it that can work even in a red state

One problem is the vast bureaucracy – a forest of agencies that have a lot of power and go largely unnoticed and unpoliced by congress. One example is that IRS agents are authorized to carry firearms. Why is that ? There was one agency that came out a few years ago: Congress and the President were not even aware of its existence. This did cause a big uproar. Makes one wonder about how many other agencies there are and what they are doing. There are some agencies that have been around for decades, having long outlived their purpose (they have probably forgotten what their purpose was), tucked away in some basement, like a windup machine that started in another century. There is a whole power structure in these agencies that is largely unchecked and unknown.

@Rafer Janders:

Well, English is not my native language and I´m little bit sleepy.

@Tsar Nicholas:

For christ’s sakes, Tsar, do you ever get tired of being an idiot?

@Tyrell:

Ok… call… what agency might this have been?

@mattb (as in the pro-gun regulation matt):

S.H.I.E.L.D.

Check these: Department of New Technology (David Reinstein: Secret government agency, Yahoo)

OMEGA agency

Check out the book “Area 51” by Annie Jacobsen; an area that has been off limits to even the presidents; this book is not about aliens from space.

@Tyrell:

ummm… right…

Thanks for demonstrating that you really have no idea what you are talking about and the entire “There was one agency that came out a few years ago: Congress and the President were not even aware of its existence.” is a load of hooie.

@mattb (as in the pro-gun regulation matt): But, mattb, the New World Order!

@Eric the OTB Lurker: I am fairly certain he only read, and then reacted to, the headline.

@Steven L. Taylor:

SHUSH MAN!

As a fellow a sworn member of the internet liberal academe elite, we’re supposed to deny the existence of the New World Order while we are still plotting with the UN and President Obama to take everyone’s airsoft pistols and precious bodily fluids away.

@Andre Kenji:

It is true that the party dynamic is different in presidential v. parliamentary systems, although the dynamic is not exactly as you describe. I would highly recommend: Samuels and Shugart, President, Parties, and Prime Ministers (which has quite a bit on Brazil in it, come to think of it).

Except the system was not designed with parties in mind at all. One of the great theoretical failings of the Framers was a lack of foresight and understanding on this topic. The development and behavior of US parties (and really, any party system) responds less to conscious design as much as to the institutional parameters under which they operate (whether the designers of those institutions understood the implications of their designs or not).

@mattb:

I do have some plans along those lines, and a blogging series mighty be a great way to jumpstart the process.

@mattb: Crud! You’re right. It must be all the holiday cheer lowering my guard!

@Steven L. Taylor:

It´s not only about the Founders. The Founders may have ignored the existence of parties, but most of the subsequent political legislation(And that includes judicial decisions) was enacted with the idea of weak and decentralized parties. One could also argue that a Plurality voting system favors weak and decentralized parties, or even that a large country tends to have weak parties.

But on the other hand the out of state money is nationalizing the Two US Parties, and that´s not good. That´s a big source of dysfunction.

I’m late to this, but I’d like to chime in with another: excellent post, thanks, and I’m looking forward to further posts on this topic.

Don’t hate the playa, hate the game…