It’s Not Time To Eulogize The Old Order

Pundits like Thomas Friedman struggle with premature prognostication.

While there has been a lot of speculation in the last several days, before and after the Russian invasion of Ukraine started, about the end of the “old order” in international relations, it’s way, way too early to declare the patient dead. In fact, every sign today seems to point in the other direction. Commitment to NATO is stronger than ever among its members, and more countries want in. Germany is increasing its military spending, and it is willing to send military aid to Ukraine. World opinion has rallied behind Ukraine, and against Putin. In Russia, demonstrators are willing to step out of the shadow of the Putin autocracy to oppose the invasion, at great risk to themselves. Economic sanctions are already hurting Russia, to the tune of a 20% key interest rate, a partial cut-off from SWIFT, the cancellation of Russian flights to international airports, and other immediate consequences. Zelensky has not fled the country, so Ukrainian morale remains high. And so on.

It’s way too early to say whether these trends will continue. It does look bad for Putin’s invasion, but no one can say for sure what the coming days, weeks, or months will bring. It is, however, way, way too early to say that the post-Cold War order has failed. Maybe the countries who operated according to the rules of the system, or the system itself as some impersonal historical force, failed to deter this invasion, but that’s not a sign that the system has failed.

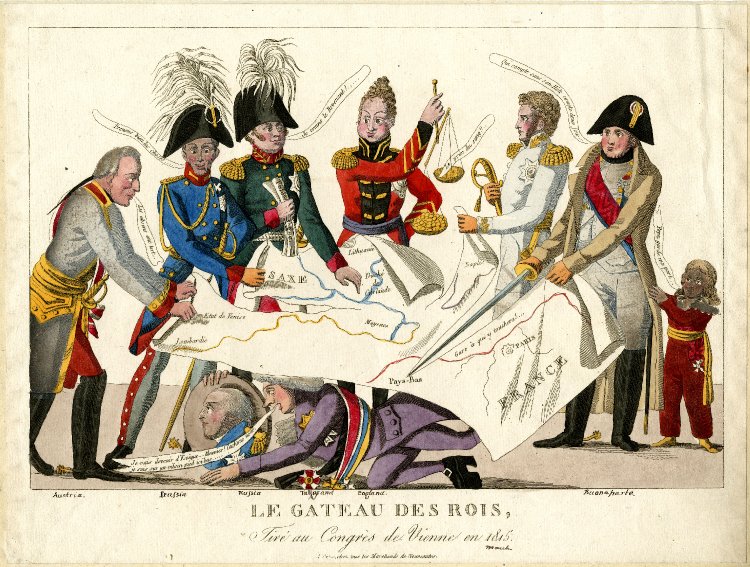

As a point of comparison, let’s look at the classic European balance of power, the “international order” that immediately comes to mind for political science wonks such as myself. The rules of that system were simple: no country should ever become a hegemon, dominating the other countries, despite their momentary or systemic advantages (Britain’s fleet, Russia’s population, Germany’s industry, revolutionary and Napoleonic France’s zeal, etc.). If anyone were to try to flip the European table, everyone else would, or should, rally to put it back to where it was.

And that’s exactly the outcome that occurred, even when some nations got painfully close to achieving hegemony. The fact that countries were willing to roll the dice and try to wreck the international order was not a sign that the order itself was irreparably broken. Whether the gambler was Louis XIV, Frederick the Great, or Napoleon, the nations of Europe eventually restored the balance — perhaps not exactly to the status quo ante, but without one nation clearly on top. It might have taken years to achieve that result, and the early days of those conflicts may have given cause for despair. However, a system that lasted a century or two, until weakened by German unification, and then smashed by two world wars, can boast a pretty good track record.

Therefore, it’s ridiculous to claim that the old order is dead, after a few days of fighting. It has certainly been weakened by Russian and Chinese efforts to undermine it. Political developments in key countries, such as Trump’s anti-NATO, pro-Putin posturing, gave cause for alarm. But as fuzzy as the rules may be of the post-Cold War consensus on how to live safely and profitably, a lot of nations are taking action to preserve it. It may have been a mistake not to oppose Russia more vigorously, and earlier, in places like Georgia, Chechnya, and Syria. It certainly looks like there were flaws in the assumptions behind the opening of China in the 1970s (a China engaged in world trade would be less aggressive and paranoid), but that was a miscalculation, not a fundamental repudiation of an international order based on respect for sovereignty (at least among the greater powers), an end to direct military conflict among the greater powers, the shift from hard power to soft power, and other tenets of the world in which we’ve lived for as long as nearly everyone reading this has been alive. There were moments of crisis when leaders like Saddam Hussein were willing to test how real and durable this system is. But it still survived.

It’s worth remembering the last time we said that “the world had changed, irrevocably,” the 9/11 attacks. With 20 years of history behind us, it’s worth asking, how much did the world really change? The United States suddenly had to face threats from terrorists (something many other countries had been dealing with for a long time). The US put more effort into counterterrorism, and then it did something both criminal and stupid, invading Iraq. The Iraqis are still living with the consequences of that mistake, as are other Middle Easterners (including the Iranian regime, which was very happy how things turned out), and to a lesser extent, the rest of the world. But what else really changed, other than security theater at the airport, or a greater investment in counterterrorism and counterinsurgency than the US had ever made before? Increased surveillance is certainly very significant, but it doesn’t really change the rules of the international order. And, it is worth noting, the backlash in the American national security community against over-emphasizing that kind of conflict over conventional warfare started at least several years ago. The American public has also lost interest in these “little wars,” to the point where Afghanistan disappeared from public debate for years, until the recent withdrawal. The 9/11 attacks were a big deal for the US, decreasingly over time, and certainly not a world historical destructive event.

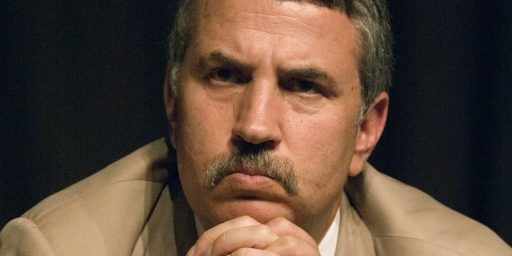

Which brings us to Thomas Friedman.

When you’re a career pundit, it’s your job to say portentous things that less serious people have presumably missed. Unfortunately, for Thomas Friedman, he is very seriously bad at making very serious prognostications, to the point where a “Friedman unit” is a synonym for bad punditry. Therefore, his declaration that “We Have Never Been Here Before” seems like another occasion when he really can’t help making instant analysis that is based on flawed assumptions and completely unjustified.

“Our world is not going to be the same again because this war has no historical parallel. It is a raw, 18th-century-style land grab by a superpower — but in a 21st-century globalized world.” Were you sleeping during Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait? Admittedly, Iraq was a regional power, not a superpower, but the threat to the international order as it existed in 1990 was pretty significant.

“This is the first war that will be covered on TikTok by super-empowered individuals armed only with smartphones, so acts of brutality will be documented and broadcast worldwide without any editors or filters.” This is truly offensive, because it overlooks the many conflicts in which social media were already a prominent source of information. Of course, the people in those conflicts weren’t white Europeans, but in the Middle East alone, we had Syria’s civil war, ongoing violence in the Occupied Territories, the rise of ISIS, popular opposition to the Iranian regime’s rigging of the 2009 election, Yemen’s awful war, Arab Spring, and other convulsive events documented in real time, through cell phones and laptops.

“Welcome to World War Wired — the first war in a totally interconnected world. This will be the Cossacks meet the World Wide Web. Like I said, you haven’t been here before.” Well, at least Friedman has devised a catch phrase, something that the talking heads will easily remember, with the added virtue of providing good blurbage for book jackets.

The rest of Friedman’s article ventures into some far more sober analysis of Putin’s chances to win this war. He also rightly points out that Xi doesn’t necessarily see China’s interests tied to Russia’s, and may not conclude from the last several days that it’s time to make a lunge at Taiwan. But then, Friedman being Friedman, he can’t help but say something silly, that Selena Gomez may have more leverage in international affairs than Putin, since he can only dream of having her 298 million Instagram followers.

We don’t really know how much social media influence international affairs. Is the democratization of knowledge a greater force for the white hats, or is disinformation a greater force for the black hats? The jury is still out. Regardless, like the unfrozen caveman lawyer in the old SNL skit, Friedman can’t help but be amazed by the magic talking box in his hand, and then go on to make some bombastic point.

Friedman’s op-ed is just the most conspicuous example of rapidly deployed predictions that have nearly zero foundation. Pundits might rightly point out that the old order is under threat, but that has happened before, during this era in international relations, as well as earlier ones. In fact, these occasional threats often remind people about the value of the system, however huge the cost in blood and treasure the lesson might impose. he old order might have weaknesses, or hidden strengths; it might be weakened by current events, or reinvigorated; it might be influenced by new technological developments, or impervious to them. All we can say is that the first reports are always wrong, or at least misleading. As another famous commentator said, “It ain’t over ’til it’s over.”

“Premature Prognostication” should be the title of Friedman’s biography.

Though I have to admit I found the anecdote that Google was accidentally revealing Russian tank movements as it notified people of traffic congestion to be utterly hilarious.

I’ve four words: The End Of History.

Not quite a decade alter Russia acquired its first authoritarian autocrat, and not two decades alter Vlad made himself, in practical terms, dictator for life.

And just a little over three decades later, the victors of the Cold War are making moves to follow in the vanquished’s footsteps.

It’s hard to make predictions, especially about the future.

Excellent piece, @Kingdaddy.

20-30 years ago, Friedman had insightful analysis, but like a lot of us as we slip into middle age and then old age, we begin to repeat ourselves. Tom is at the ‘get off my lawn’ stage of his career.

Good post.

Friedman being Friedman. A lot of truth but also some weird stuff. His preceding column on NATO’s alleged responsibility for Putin’s warmongering was more oddball than this one, at least this one had kind of a point regarding the TikToking of this invasion. I truly don’t think Putin factored in Ukrainians being able to use cell phones and social media to bypass the Kremlin’s propaganda.

“The American media is lying!” says a Russian bot. Maybe, but that live video call I had with my buddy in Kyiv is not lying so…

Is this prevailing opinion about 9/11 and Iraq in the poli sci field? I’d say these events probably did irrevocably change things far past airport security tedium, based on the point made at the beginning of this post: WW1 is still echoing. It echoed through WW2, which fueled the Cold War, which played into 9/11 and the Bush Wars.

Which brings us here.

Isn’t there a through line from 9/11 and Iraq/Afghanistan to Ukraine? Those events increased American paranoia, conspiracy theorism, and distrust for official narratives from media and goverment. All of which a) are being wraponized by Putin and Xi against democracy, b) helped fuel Trumpism, and c) allowed coronavirus to weaken, fatigue, and divide the West. Putin is even directly citing Iraq/Afghanistan to justify his invasion.

Iraq/Afghanistan also helped decrease trust in the military and political establishments across the West, including in the US, UK, and Europe. That helped fuel the rise of progressives on the left and isolationist conservatives on the right, including Brexiteers like Farage. Left wing distrust of Hillary stemming from her Iraq War vote contributed to the rise of both Obama and Bernie, whose challenge to Hillary was weaponized by Wikileaks/Putin to benefit Trump. In contrast her, Obama was arguably too weak at challenging Putin, and Trump openly helped Putin weaken NATO and Ukraine.

Iraq and Afghanistan also bled the US of treasure and increased our war weariness. Arguably Putin would not be in Ukraine, or would have met an American-led NATO army there in 2014 or now, if not for an economically distressed, divided, and war weary American public. That’s connected to how Iraq and Afghanistan changed America into a pacifist nation.

9/11 and the Bush wars are clearly not the only factors affecting today’s international order (social media, globalist trade, the neverending fight over Israel, climate change migration, COVID are some other factors). But they probably did irrevocably change things: conflicts just keep growing out of previous, sometimes decades-old wars.

So it does have a historical parallel. (At least that what I’m hearing when he blathers.)

Friedman is about 20 years out of date technology-wise. I bet he has a landline, and answers it. Wireless World War would have been a better phrase. Cossacks meet TikToks.

Can’t believe I agree with Friedman…I have no idea about the ‘old order’ but this is the end of ethnonationalism in America and Europe for people under 30. The utter end, unless you’re an incel or something. When Germany let in a huge number of refugees, it was supposedly the end of Merkel and her party and multiculturalism. Never happened. Now a more-left Germany is getting ready to start building fighter jets to fight a dying version of empire.

Also, I think watching the Ukraine fight against Russians, who are more or less kin, has made it clear that in London, LA, Berlin, NYC, or wherever supposedly you don’t have a connection to people who don’t look ‘exactly’ like when your back is against the wall all backs are against the wall. Kiev seems universal to anyone who has a life. An army led by nationalist trash invades blathering retrograde propaganda about gays or some shit and you resist because you have more connections to your actual neighbors than to some bullshit myth about origins or some dumb fucking religion which nobody invading believes in.

I am very surprised about how quickly and effectively the Old World Order fell into line to confront this current threat from Russia.

The vaunted Russian disinformation campaigns of the post-Truth world didn’t have any effect — more than the European-plus countries of NATO holding together (which is surprising on its own), a large chunk of the rest of the world is lining up behind the American/EU sanctions, including traditionally squishy and problematic countries.

The economic warfare is a bit new — and the sanctions, flight restrictions, etc. really do become a new form of warfare. There have been naval blockades in the past, and mining of harbors, but this is a bloodless (for us) shunning where the Old World Order has just turned their back on Russia.

US sanctions run deep into the chip industry, so Russia is already getting cut off on microchips from China.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2022/02/25/ukraine-russia-chips-sanctions-tsmc/

Overall, it’s a bad time to attack a country of white, mostly-Christian people with a vibrant, telegenic leader who voiced Paddington Bear. Europe and its white former colonies stands united against that, and is bringing along a good chunk of the others to one extent or another. Best to go after darker people with less accepted religions, whose leaders have voiced other, lesser animated animals.

(Zelenskyy is Jewish, but most of Ukraine is Christian… if Putin were to focus his “denazification” on just the Jews, he might not have gotten this much pushback)

I do think Friedman gets over his skis here (not surprising), but I don’t think he’s wrong about the general historical importance of what’s going on, which is the culmination of events over the last 30 years.

This is the first major state-on-state conflict that wasn’t conducted by the US or our allies since the end of the Cold War. And the reason that is significant is that it’s the first major challenge to the so-called global liberal order which has expanded under US leadership for the last 30 years.

Those of us who study history know that hegemonic power always brings challengers and opposition. As much as we in the US like to believe that our shit doesn’t stink and that our various systems – political, social, economic, and others – are the best, that all others are destined to emulate us and our values, the reality is that not everyone on our beautiful blue planet shares our values and goals, much less accepts the US as the hegemonic power who should rightfully enforce them.

And so – inevitably – resistance has been building over the last three decades to the US-led global liberal order. No one should be surprised at this.

The primary centers of that resistance have been in China, Russia, and parts of the Islamic world. As the US and allies expanded our sphere of influence into new areas that Russia, China, and others consider to be vital strategically, resistance stiffens, and red lines are drawn. Ukraine is important in this geostrategic context because it is where Russia drew a red line.

In contrast to Russia, our policy toward China has been much more cognizant of geostrategic reality. We still nominally support China’s “one China” policy and have steadfastly kept Taiwan in a grey zone where we do not have formal relations or a formal military alliance, but we still implicitly giving Taiwan unwritten assurances that we will guarantee their independence against Chinese aggression – it’s a tricky balance that we’ve been able to maintain for over 40 years. It’s been a wise policy that has produced stability and diverted competition with China to other areas.

Consider how things would be different if, in 2008, we began to float the idea of granting Taiwan diplomatic recognition as an independent nation. And not only that, but dangling the possibility of a formal military alliance with Taiwan. Suppose NATO was also a Pacific alliance that anyone could join and Taiwan applied for membership. Most scholars, I think, would agree that China would go to war to prevent any of that from happening. Taiwan joining a hostile alliance would be intolerable for China and would precipitate an attack to take Taiwan by force before that could happen.

For me, part of the tragedy of this war is our leaders and political class did not see these obvious parallels and thought that Ukraine was different. After all, Taiwan has been independent for far longer than Ukraine. Our policymakers believed that Russia could either be convinced of the righteousness of our position, of the inherently benign nature of NATO, or that we could simply ignore Russian objections as we had done many times before without consequence. Whether a US policy toward Ukraine that was more like our policy toward Taiwan would have avoided the current tragedy is impossible to know at this point.

People may not remember, but this was heavily debated in the 1990’s. Thomas Friedman was one of the many NATO-expansion skeptics. The most important and knowledgeable skeptic was George Kennan, architect of the Cold War “containment” strategy. He along with others who understood Russia, and the history of East-West relations cautioned against it and predicted that NATO expansion would result in exactly what is happening today.

As Kennan wrote in 1997:

Note the part about executive power in Russia being in a high state of uncertainty. That just happened to be at the same time that Putin was in the midst of moving from local St. Petersburg politics to national politics in Moscow…

I think it’s hard to argue that Kennan wasn’t prescient about what NATO expansion would bring.

Kenna wasn’t alone, Vox has a rundown of this history and other players.

Anyway, most of this is irrelevant at this point and my own frustration at being correct in my analysis when I wish I wasn’t. I can only hope that once this conflict is over – hopefully with a decisive Russian defeat – we here in the US and the West will reassess our own policies and more seriously consider geopolitical realities, effects, and limitations. Friedman, in his own half-assed and peculiar way, takes a nibble at that apple in this essay.

I would just add and say that with the War on Terror it was impossible to have war heroes, unless you were an Iraqi or in Afghanistan fighting Americans, or a total moron. The conditions were not right. Hitler was an authentic war hero to Germans, or at least he represented all of the German soldiers in that war. The conditions were right for Hitler. Zelenskiy has become a war hero, and there’s just very little recent precedent for that in the west. Nobody in Europe or America has had an actual heroic war in their world since WW2.

Suppose NATO was also a Pacific alliance that anyone could join and Taiwan applied for membership. Most scholars, I think, would agree that China would go to war to prevent any of that from happening.

Short of giving back the Warsaw Pact to Putin in a deal, what would you have anybody do here? In 2021, Biden deferred when the Ukraine asked for NATO membership–oddly enough, they weren’t exactly comfortable with Putin. The Ukraine doesn’t want to be part of Russia, plain and simple. NATO can’t undo that. They can’t undo the fact that Putin’s government is not something other countries want.

Ukraine will fall for sure, but the occupation will be hell. I know generations of Ukrainians who have been waiting for just this moment.

Friedman is an idiot.

He gets monofocused on one shiny thing and cannot let go. E.g., The World Is Flat.

Friedman keeps trying to make “fetch” happen. It’s not going to happen.

@Andy:

Ukraine shares Putin’s values? This is not about “everyone on the planet,” it’s about Ukraine. As usual with the “Blame NATO” crowd (including Putin), you forgot to care about what Ukrainians want.

It’s actually Putin and the anti-NATO crowd who can’t let go of the idea of the US as a hegemonic power with impeachable values. That idea died sometime between the invasion of Iraq and the inauguration of Donald Trump and was officially buried when the US left Afghanistan last year.

The US didn’t isn’t leading NATO armies into Russia, Belarus, or Ukraine to force US policy. US policy is that Ukraine should decide Ukraine’s fate.

The Greenwald/Tracey/Taibbi Contrarion Cult has to ignore that because it doesn’t match the intellectually lazy bothsides square peg they want to force into the round hole of Putin’s insanity. It’s also how they beclowned themselves this month, falling for Putin’s lies about not invading.

You’d think now they’d reconsider falling for Putin’s “NATO made me do it” and Trump’s “Russia hoax” lies as well. But.

@Andy:

What’s happening today is not a result of NATO expansion. That’s Putin’s propaganda. What’s happening is a result of NATO not expanding far enough: Putin continues to attack his non-NATO neighbors.

Putin is not attacking Ukraine because of NATO. NATO has never attacked Russia, and he knows its not a threat. He’s attacking Ukraine because he’s an aging, paranoid, isolated megalomaniac who is stuck in the past and thinks his neighbors have no right self-determination.

Putin is afraid of democracy, not NATO.

@Andy:

Or suppose the United States was led by a dictator who murders, poisons, and jails political opponents, who had flattened Havana to seize Cuba in 2000, invaded Canada in 2008, then annexed Baja California in 2014, followed with claiming the rest of Mexico had no right to exist. After Mexico had given up nukes to the US in 1994 with a US promise to never invade or attack Mexico.

You wouldn’t need to be a scholar to agree with Mexicans wanting to join an security alliance with countries that weren’t paranoid, untrustworthy, violent, and crazy towards neighbors.

It’s astonishing that so many presumably intelligent and informed people are rushing to draw heroic conclusions about the consequences of an invasion which began five (5) days ago. Did anyone warble on September 6 1939 that Herr Hitler had made a huge error? If they did, I don’t suppose they admitted it later. The truth is nobody has a clue what the consequences of this conflict are going to be, no matter how many sage tweets are sagely tweeted.

I do, however, fearlessly draw one conclusion. The Project for a New American Century is dead.

@Modulo Myself:

Pfft. Warsaw Pact doesn’t go back far enough for Putin. He’s mad at Lenin for carving out Ukraine. Try Tsarist Imperial Russia.

It’s interesting how much perceptions can differ. No time for an in-depth today but after reading that I’d find it hard to argue he got anything right.

@Andy:

Perhaps; I’ve often seen it argued that “county x” does not desire “western-style” democracy.

And often thought: “Hmm. Do they get a vote on that?”

@Andy:

That would presumably depend upon your definition of “major”.

Some conflicts post-1990 that you are, I assume, defining as “non major” (unless you have a very flexible category of “US ally”):

Croatian-Yugoslav/Serbian War 1991-95 (categorised state on state as Croatia was de facto independent from 1990)

Transnistria-Moldova War 1992

Armenian-Ajerbaijan War (aka Nagorno Karabakh War) 1994

Eritrea-Ethiopia War 1995-2000

Russia-Georgia War 2008

and the Russian-Ukraine conflict in 2014.

You might note a fair number involved Russia or Russian proxies.

A number that rises when “sub-state” conflicts such as Chechnya are included.

@Andy:

Regarding Taiwan, the US may not have a formal alliance or the NATO style “automatic war” trigger.

But it has been pretty clear that the US does provide a de facto military guarantee to Taiwan, but with the proviso that it is subject to Congressional approval.

@Andy:

In relation to Ukraine, it is notable that the trigger for the Russian attack in 2014 was not any prospective NATO membership, but the prospect of economic alignment with the EU.

And also the departure of Yanukovych and the increasing escape of Ukraine from the kleptocratic pseudo-democracy model of Russia, Belarus, and pre-2014 Ukraine.

The question might be, is Russia to be granted a right to require certain states to subordinate their economise and security to the wishes of the Kremlin?

To how many countries does such caveated independence apply, beside Ukraine and Belarus?

Is such a category liable to adjustment by Russia when it desires?

Which other states have similar rights over neighbouring, “lesser” countries?

Or might claim such in the future?

I would argue a significant part of the outrage in Europe at Russia’s action are that the Continent has generally decided that such assertions of “historic” or “ethnic” or “the Rights of Powers” are unconscionable atavistic machtpolitik.

@JohnSF:

Exactly. It is sickening to see Americans argue that some countries have no future but subordination. It’s like advising a rape victim to lie back and try to enjoy it.

A reminder as to what Americans believe. “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.–That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed-“

The only legitimate form of government is that which derives its power from the consent of the governed. Everything else is tyranny. That is America 101. Nothing in the Declaration about having to kowtow to neighboring thugs, about the weak having to submit to the strong. I just despise this facile cynicism, this oh-so-worldy-wise dismissal of other people’s liberty and lives.

@Modulo Myself:

Brits beg to differ.

Falklands.

(A bit pointless, in strategic terms, arguably; but from the POV of the rights of populations, pretty sound)

Have to admit though, it pales before what Zelensky and Ukrainians are doing.

Just hope it ends as well.

@JohnSF:

Borges said that the Falklands was like a fight between two bald men over a comb.

@Modulo Myself:

Hey, that’s me these days!

I always said, if the Argentinians had been sensible, they’d have offered every Falklander a million quid (in hard currency. LOL) and a wine estate in the Mendoza Hills.

Suspect wouldn’t have seen the Islanders for dust; only problem might be new migrants from Britain trying get squatters rights for the deal.

UK govt. had been quietly trying to offload the Islands for decades. And Brits in general wouldn’t have cared a bit about a peaceful transfer. Just a handful of nutty Empire nostalgists, if that.

But no, the Buenos Aires junta had get all “they are ours, we seize them for out national pride” about it.

So of course we Brits, being a prickly lot, punched back.

But twice as hard. It’s how we are.

We’d have given it; but we’d be damned to have it taken.

@DK:

Lots of replies and I have little time, so I’ll focus on responding to you.

Most of what you claim here in your other responses is factually wrong or misleading and, in some cases, strawmans what I actually wrote.

The fundamental mistake is your insistence this is all about Putin and how evil he is and that nothing else matters, particularly the effects of NATO expansion. This line of argument suggests that if only Putin were not in power, then Russia and Russia’s government would be fine with Ukraine joining NATO and would be fine with NATO expansion. And by asserting that this conflict is entirely and only about Putin, you (and others) suggest that the US and NATO don’t bear any responsibility for the standoff that was the precursor to this war, and that Russia’s strategic interests are actually fake.

Contrary to your assertions, NATO expansion is central to understanding why this war is occurring. And let’s get some throat-clearing out of the way – understanding the circumstances is not placing blame. We can, for example, understand that US policy in the Middle East contributed to the rise of Islamist terrorism that resulted in 9/11 and other attacks. That is well known. State that should not be interpreted as an argument that the United States is to blame for 9/11. The same goes for analyzing the situation in Ukraine.

Now, with that out of the way, the fact is that Russia strongly opposed NATO expansion from the beginning before anyone knew who Putin was. So when I say Russia, I do not mean only Putin, but also Yeltsin, the Russian government, the Russian elite, and also the Russian people.

The public evidence for the centrality of NATO expansion is overwhelming.

In 1994 Yeltsin told President Clinton at the outset of NATO expansion:

Bill Burns, who currently is President Biden’s CIA director, issued warning after warning over the previous three decades in his various diplomatic positions. These are some quotes from his memoir on the matter, The Back Channel (which I happen to own):

1995:

In a 2008 personal memo to Condi Rice, then SECSTATE, (emphasis added):

Note that a few months later, after Burns’ advice was ignored, there was a war in Georgia over this very question. The point is, what’s happened in Ukraine has happened before and for the same reasons.

Fiona Hill, the Russia expert that worked for three administrations and became famous in Trump’s impeachment wrote this in January where she lays basically the same things Burns, Kennan, and many others have said, only in starker terms.

There are classified State Department memos courtesy of WikiLeaks that discuss all of this in official correspondence. I won’t link them here to avoid any possibility of getting James in trouble (going to Wikileaks on a government computer can cause…problems), but they are easy enough to fine.

I mean, I could spend all night laying out more supporting information and evidence. And we could go into Russia’s history (Russia’s been fighting wars to protect its southern flank for 300+ years and has been invaded three times by western powers in the last 200), the paranoid style of its culture (pretty freaking paranoid), and its obsessive and complicated relationship with the West (really complicated – again going back centuries).

But for the last quarter-century, NATO expansion has been the key dispute between Russia and the US/NATO. To suggest it is irrelevant and only has to do with Putin is completely contrary to the evidentiary record. To suggest that Russia has no strategic interests in Ukraine is similarly ignorant.

@Andy: Andy I suggest you are misreading American actions and intentions. It’s likely successive administrations understood very well the likely response of Russia to an extension of NATO. But they went ahead with it anyway as a deliberate containment policy, to prevent the old Soviet empire ever being re-established. Remember the dominant goal in the days of the Project for a New American Century was to prevent any other nation ever being able to challenge American global hegemony. If Russia didn’t like it, tough shit. There was nothing they’d be able to do about it. They’d been crippled.

The Europeans, unsurprisingly, were a bit reluctant to get wholly on board with this vision of the future. What wrecked it was 20 years of military blunders and misadventures in Afghanistan and the Middle East, coupled with the rise and rise of China. The humiliating impotence of the global hyperpower to prevent a shithole country like North Korea acquiring both nukes and ICBMs also blew holes in the whole set of assumptions underpinning the PNAC vision.

All that history bespeaks hubris, egregious errors of judgement, historical ignorance, a failure to grasp the endlessly shifting forces driving global political economy. But it doesn’t mean Washington didn’t understand how its actions would be received in Moscow. In fact its goal – pre-emption of any revival of Russian greatness – was exactly what Putin is now complaining about. It just means Washington knew very well, but didn’t give a damn.

And none of that history goes anywhere near justifying Putin’s war of aggression.