Seventh Circuit Strikes Down Indiana And Wisconsin Bans On Same-Sex Marriage

Another Federal appellate Court has struck down state law bans on same-sex marriage, but the only thing that matters now is the Supreme Court.

Late yesterday, the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals became the latest Federal appellate court to strike down state law bans against same-sex marriage, thus increasing the number of cases that the Supreme Court will have before it on this issue when the new term begins next month:

Only nine days after hearing arguments in the case, a federal appeals court in Chicago declared the bans on same-sex marriage in Indiana and Wisconsin to be unconstitutional on Thursday, adding to the list of marriage cases that could wind up before the Supreme Court in the year ahead.

“The grounds advanced by Indiana and Wisconsin for their discriminatory policies are not only conjectural; they are totally implausible,” said the unanimous opinion by a three-judge panel of the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, as it confirmed lower-court decisions that reversed marriage restrictions in the two states.

The ruling by the Seventh Circuit joins similar appeals-court decisions that overturned same-sex marriage bans in Oklahoma, Utah and Virginia, with still other circuit court rulings on marriage expected in the weeks ahead.

In each case so far, the rulings to permit same-sex marriages have been temporarily stayed, pending action by the Supreme Court, and the same appeared likely for Indiana and Wisconsin.

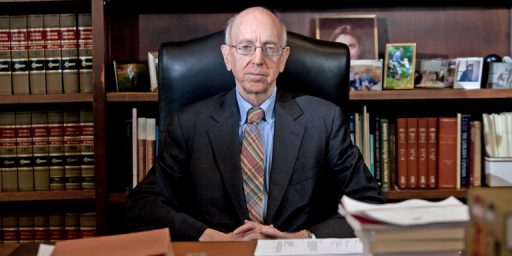

Thursday’s opinion was issued with unusual speed and written by Judge Richard A. Posner, an appointee of President Ronald Reagan who is known for his tart words and independent thought.

“We’ll see that the governments of Indiana and Wisconsin have given us no reason to think they have a ‘reasonable basis’ for forbidding same-sex marriage,” Judge Posner wrote near the opening of the 40-page opinion.

The argument that allowing same-sex marriage will somehow undermine the protection of children in heterosexual marriages, the court said, “is so full of holes that it cannot be taken seriously.”

Both states argued that their electorates should have the right to continue policies based on centuries of tradition. Traditions can be harmful, such as foot-binding, Judge Posner wrote, or innocuous, such as handshaking. But if a tradition is “written into law and it discriminates against a number of people and does them harm,” he wrote, “it is not just a harmless anachronism; it is a violation of the equal protection clause.”

To the states’ arguments that the issue should be left to democratic majorities in each state, the court responded: “Minorities trampled on by the democratic process have recourse to the courts; the recourse is called constitutional law.”

Wisconsin and Indiana officials immediately said they would appeal Thursday’s decision to the Supreme Court.

While we have largely reached the point where there are few differences between the various court opinions that have struck down state law marriage bans, Lyle Denniston notes that the 7th Circuit’s opinion differs significantly in many respects:

The Seventh Circuit’s combined ruling in Baskin v. Bogan (the Indiana case) and Wolf v. Walker (the Wisconsin case) took a markedly different approach from that employed in many of the federal courts’ rulings against bans on same-sex marriage. It had as much philosophical and sociological content as legal analysis, and it used a good measure of sarcasm about and even something close to disdain for the two states’ arguments. Although decided by a three-judge panel, it had the distinctive style of its author, Circuit Judge Richard A. Posner, a jurist with a sharp wit, a devotion to scholarship, and an eclectic range of public policy interests, many non-judicial.

In this opinion, he even made use of the writings of the nineteenth-century English political philosopher and social commentator, John Stuart Mill, in dismissing the states’ arguments that many people find same-sex relationships repulsive.

As for legal arguments, the Posner opinion decided only the claim of discrimination in the two states’ bans on same-sex marriage and thus stayed away from the debate that figured in many cases about whether such bans violated a fundamental right — keyed to due process guarantees – for same-sex couples to enter marriage equally with opposite-sex couples.

In finding that the two states’ laws do discriminate against same-sex couples, the Seventh Circuit’s ruling avoided applying a more demanding constitutional test, concluding that the bans at issue were “irrational and therefore unconstitutional.” The “rational basis” test is the mode of analysis that is most generous to challenged to state laws.

Indiana has banned same-sex marriages by state law since 1997; it does not have a ban in its state constitution. Wisconsin voters approved a ban in their state constitution in 2006, by a margin of fifty-nine to forty-one percent.

The decision against both states’ bans contained no discussion of when the ruling would take effect, and thus left open the prospect that officials from the two states could seek a postponement so that they could pursue the option of going to the Supreme Court.

In many respects, the fact that the opinion comes at the issue of marriage rights from a different perspective can be attributed to its author, Judge Richard Posner. Posner has been on the 7th Circuit for more than 30 years at this point, and while he has generally been thought of as a “conservative” in the legal community due to the academic work he has done off the bench in the area of law and economics, he has been far more independent of the “conservative” label than that label might have led him to believe. In recent years, for example, he has been openly critical of several Supreme Court opinions, typically in academic writing rather than judicial opinions where he is bound to follow the Court’s rulings as binding precedent, in cases such as Citizen United. On issues of personal liberty, he is probably more fairly described as a libertarian akin to Justice Kennedy, who has authored all three of the Supreme Court’s ground-breaking opinions in the area of gay rights.

In this particular case, it was clear from the time that oral argument was conducted nine days ago that Posner was skeptical of the arguments made by the representatives from Indiana and Wisconsin, and that comes out quite strongly in his opinion. For example, at one point, he points out that Indiana’s ban on same-sex marriage seems to be logically inconsistent with its own marriage laws in light of the fact that state officials had relied on the idea of protecting children as one of the primary arguments in favor of the ban:

First up to bat is Indiana, which defends its refusal to al-low same-sex marriage on a single ground, namely that gov-ernment’s sole purpose (or at least Indiana’s sole purpose) in making marriage a legal relation (unlike cohabitation, which is purely contractual) is to enhance child welfare. Notably the state does not argue that recognizing same-sex marriage undermines conventional marriage.

(…)

In short, Indiana argues that homosexual relationships are created and dissolved without legal consequences be-cause they don’t create family-related regulatory concerns. Yet encouraging marriage is less about forcing fathers to take responsibility for their unintended children—state law has mechanisms for determining paternity and requiring the father to contribute to the support of his children—than about enhancing child welfare by encouraging parents to commit to a stable relationship in which they will be raising the child together. Moreover, if channeling procreative sex into marriage were the only reason that Indiana recognizes marriage, the state would not allow an infertile person to marry. Indeed it would make marriage licenses expire when one of the spouses (fertile upon marriage) became infertile because of age or disease. The state treats married homosexuals as would-be “free riders” on heterosexual marriage, un-reasonably reaping benefits intended by the state for fertile couples. But infertile couples are free riders too. Why are they allowed to reap the benefits accorded marriages of fer-tile couples, and homosexuals are not?

The state offers an involuted pair of answers, neither of which answers the charge that its policy toward same-sex marriage is underinclusive. It points out that in the case of most infertile heterosexual couples, only one spouse is infer-tile, and it argues that if these couples were forbidden to marry there would be a risk of the fertile spouse’s seeking a fertile person of the other sex to breed with and the result would be “multiple relationships that might yield unintentional babies.” True, though the fertile member of an infertile couple might decide instead to produce a child for the cou-ple by surrogacy or (if the fertile member is the woman) a sperm bank, or to adopt, or to divorce. But what is most unlikely is that the fertile member, though desiring a biological child, would have procreative sex with another person and then abandon the child—which is the state’s professed fear.

The state tells us that “non-procreating opposite-sex couples who marry model the optimal, socially expected behav-ior for other opposite-sex couples whose sexual intercourse may well produce children.” That’s a strange argument; fer-tile couples don’t learn about child-rearing from infertile couples. And why wouldn’t same-sex marriage send the same message that the state thinks marriage of infertile heterosexuals sends—that marriage is a desirable state?It’s true that infertile or otherwise non-procreative heterosexual couples (some fertile couples decide not to have children) differ from same-sex couples in that it is easier for the state to determine whether a couple is infertile by reason of being of the same sex. It would be considered an invasion of privacy to condition the eligibility of a heterosexual cou-ple to marry on whether both prospective spouses were fer-tile (although later we’ll see Wisconsin flirting with such an approach with respect to another class of infertile couples). And often the couple wouldn’t know in advance of marriage whether they were fertile. But then how to explain Indiana’s decision to carve an exception to its prohibition against marriage of close relatives for first cousins 65 or older—a population guaranteed to be infertile because women can’t con-ceive at that age? Ind. Code § 31-11-1-2. If the state’s only interest in allowing marriage is to protect children, why has it gone out of its way to permit marriage of first cousins only after they are provably infertile? The state must think marriage valuable for something other than just procreation—that even non-procreative couples benefit from marriage.

And among non-procreative couples, those that raise children, such as same-sex couples with adopted children, gain more from marriage than those who do not raise children, such as elderly cousins; elderly persons rarely adopt.

Indiana has thus invented an insidious form of discrimination: favoring first cousins, provided they are not of the same sex, over homosexuals. Elderly first cousins are permit-ted to marry because they can’t produce children; homosexuals are forbidden to marry because they can’t produce children. The state’s argument that a marriage of first cousins who are past child-bearing age provides a “model [of] family life for younger, potentially procreative men and women” is impossible to take seriously.

Posner’s treatment of the Wisconsin statute goes along similar lines:

The state’s argument from tradition runs head on into Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967), since the limitation of marriage to persons of the same race was traditional in a number of states when the Supreme Court invalidated it. Laws forbidding black-white marriage dated back to colonial times and were found in northern as well as southern colonies and states. See Peggy Pascoe, What Comes Naturally: Miscegenation Law and the Making of Race in America (2009). Tradition per se has no positive or negative significance. There are good traditions, bad traditions pilloried in such famous literary stories as Franz Kafka’s “In the Penal Colony” and Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery,” bad traditions that are historical realities such as cannibalism, foot-binding, and suttee, and traditions that from a public-policy standpoint are neither good nor bad (such as trick-or-treating on Halloween). Tradition per se therefore cannot be a lawful ground for discrimination—regardless of the age of the tradition. Holmes thought it “revolting to have no better reason for a rule of law than that so it was laid down in the time of Henry IV.” Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., “The Path of the Law,” 10 Harv. L. Rev. 457, 469 (1897). Henry IV (the English Henry IV, not the French one—Holmes presumably was referring to the former) died in 1413. Criticism of homosexuality is far older. In Leviticus 18:22 we read that “thou shalt not lie with mankind, as with womankind: it is abomination.”

The limitation on interracial marriage invalidated in Loving was in one respect less severe than Wisconsin’s law. It did not forbid members of any racial group to marry, just to marry a member of a different race. Members of different races had in 1967, as before and since, abundant possibilities for finding a suitable marriage partner of the same race. In contrast, Wisconsin’s law, like Indiana’s, prevents a homo-sexual from marrying any person with the same sexual orientation, which is to say (with occasional exceptions) any person a homosexual would want or be willing to marry.

Wisconsin points out that many venerable customs appear to rest on nothing more than tradition—one might even say on mindless tradition. Why do men wear ties? Why do people shake hands (thus spreading germs) or give a peck on the cheek (ditto) when greeting a friend? Why does the President at Thanksgiving spare a brace of turkeys (two out of the more than 40 million turkeys killed for Thanksgiving dinners) from the butcher’s knife? But these traditions, while to the fastidious they may seem silly, are at least harmless. If no social benefit is conferred by a tradition and it is written into law and it discriminates against a number of people and does them harm beyond just offending them, it is not just a harmless anachronism; it is a violation of the equal protection clause, as in Loving. See 388 U.S. at 8-12.

There’s much more to Posner’s opinion, of course, and it is worth reading if only because it provides a somewhat different take on the argument against bans against same-sex marriage bans that may end up of being of interest to the Justices of the Supreme Court when this matter finally gets before them. Rather than looking at the question of whether or not the Fourteenth Amendment includes some kind of fundamental right to marriage, which is the argument that was rejected by a Federal District Court Judge in Louisiana as James Joyner noted earlier this week, Posner comes at this completely from the perspective of the Equal Protection Clause. One advantage of this argument for advocates of the marriage equality position is that making this argument doesn’t necessarily require a Judge to agree that the 14th Amendment was intended to include a right to same-sex marriage. Instead, the relevant question becomes whether there is any rational basis at all for discriminating against a class of citizens, in this case gays and lesbians, in granting a the legal benefits of marriage. Even under the lowest level of review for equal protection cases, the rational basis test, it seems next to impossible to come up with an argument that would justify such discrimination. The arguments cited by Indiana and Wisconsin, tradition, encouraging procreation, and protecting children, simply don’t stand up to a rational argument when you consider the fact that all of them fall apart when applied to opposite sex marriages that the state already recognizes. If there’s no rational basis for making the distinction, then the ban on same-sex marriage cannot stand.

As I’ve noted recently, these individual court decisions don’t mean nearly as much as they used to. All of the arguments in favor of the bans, and all of the arguments opposed to them, have now been fully argued and litigated in countless courts throughout the country. While the law is hardly a democracy, the overwhelming weight of judicial opinion on the issue has come down decidedly on one side, and those opinions have been authored by Judges who were appointed by both Republicans and Democrats. To some extent, I suppose, it is notable that a third Circuit Court of Appeals has come down against state law bans on same-sex marriage, and an opinion from someone as prominent among the Federal Judiciary as Richard Posner is likely to carry weight further down the line. In the end, though, all of this is merely a prelude for the inevitable consideration of these laws by the Supreme Court. As things stand now, there are appeals in process in the cases from Virginia, Utah, and Oklahoma. No doubt, these cases from Indiana and Wisconsin will join them, and there are four cases awaiting a decision from the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals that could be released at any time. The only question at this point is whether the Justices will accept one or more of these appeals, and I think they probably will, and how they will rule on them.

Here’s Judge Posner’s decision: