The Myth of Picking the Best

And yes, it is political (and always has been).

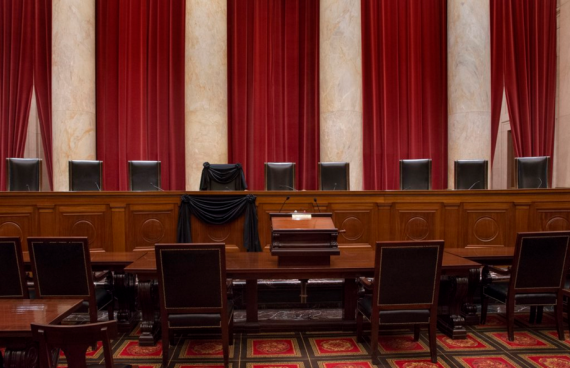

The pending retirement of Justice Stephen Breyer (and the discussion thereof here on the site) has me thinking about issues surrounding meritocracy, judicial appointments, and the general mythology of SCOTUS. These thoughts also intersect with my post from a couple of weeks ago, SCOTUS Mythology Exposed.

Let’s start with the meritocracy issue and the issue of picking “the best” or “most qualified” nominee. More than anything I want to note that these concepts are repeatedly conflated in these discussions. If Biden nominates Ketanji Brown Jackson, it will be a meritocratic choice because her career merits consideration for the position. She is a graduate of Harvard Law School (where she was editor of the law review). She had several federal clerkships (to include clerking for Breyer). She has, among other things, practiced law, been a public defender, and served on the federal bench (the US District Court for DC and the United States Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit).

If one encountered that list of qualifications on a c.v. without a name, one would likely agree that the person with that experience would be qualified, on the merits of that career, to be considered to be nominated. It certainly is not the resume of someone undeserving of consideration. In plain terms, she is someone who lacks the merit needed for consideration.

Now, is that resume of The Best and Most QualifiedTM candidate out there? I don’t know, and nor does anyone else. That is a subjective assessment. Is, as Ilya Shapiro asserted, Sri Srinivasan a better candidate and therefore is Jackson “lesser” one? Sure, Srinivasan has been on the Court of Appeals longer. Maybe his experience in the Solicitor’s General office is “better” than Jackson’s public defender stint (or, arguably, maybe not). Again, this becomes a game of weighing variables that do not have an objective scale (and, ultimately, of opinions).

Anyone who has been involved in assessing a pool of applicants for a job knows full well that while some judgments are objective (a candidate with a BA objectively has more education than someone with a GED) others are subjective. The actual weighing of candidates has a great deal of art to go along with the science.

Picking “the best” is not as easy as some want it to sound.** I know I have been involved in hiring people who seemed to be a slam-dunk choice, but ended up not quite being all they were cracked up to be.

Let’s also face a truth that is hard to deny (although some might try): inevitably, as soon as a president states that they going to pick a candidate with attribute X (female, Black, etc.) the cries will begin that the criteria should be the “most qualified” or “the best possible” candidate. Or, even if such an announcement is not made, the selection of anything other than a white male will result in someone, somewhere with some level of prominence asserting it was tokenism in some way, form, or fashion. This suggests that a lot of people unconsciously assume that “the best” and “most qualified” candidates have to be white males (since it is rather rare that we have a national conversation as to the qualifications of those nominees because of their whiteness or maleness).

Look, I fully understand the abstract notion that it would be great if things were so perfectly just that we didn’t have to worry about seeking representation, but this is not the world we inhabit. Note that what the words “affirmative action” mean: a positive step towards recognizing that we do need to be cognizant that without paying attention, a system is prone to replicate itself. And there is value in saying that race and gender should be considered when given a choice of this nature. It does matter for the most powerful institutions of government to include diverse voices.

As such, I see nothing wrong with taking into consideration race and gender in particular, given our national history, when picking a nominee. Such choices do not mean that one isn’t still picking in a meritocratic fashion.** It just means other factors matter too.

There are only nine*** of these jobs and a given president may get only one appointment. By definition, any singular nominee will have strengths and weaknesses and pundits and pols will always be able to claim that some other person would have been “better” in their view.

Not long after I started writing this post, I inadvertently clicked on a tab that had Twitter open, and at the top of the feed at that moment was this piece from The Hill: Collins: Biden’s campaign pledge to nominate Black woman to court politicized nomination process.

Sen. Susan Collins (R-Maine) said on Sunday that President Biden‘s campaign promise to nominate a Black woman to the Supreme Court “helped politicize the entire nomination process” as opposed to when former Republican President Trump and President Ronald Reagan chose to also nominate women to the high court during their tenures.

Collins said on ABC’s “This Week that she would “welcome the appointment of a black female to the court,” but said the way Biden has approached the nomination has been “clumsy at best.”

“It adds to the further perception that the court is a political institution like Congress when it is not supposed to be. So I certainly am open to whomever he decides to nominate. My job as a senator is to evaluate the qualifications of that person under the advice and consent role,” Collins said.

Without getting into the Susan Collinsness of it all, let me note that this is a perfect illustration of a lot of the prevailing American mythology about the Court. The assertion, which is pretty common, that the Supreme Court is not “political” is among the more ridiculous things one can say about an institution that this populated with clear political intent by politicians and whose function is to make authoritative, binding legal decisions that affect national policy and thereby the lives of millions. The Court exercises political power, plain and simple. It is true that they do not officially have Rs or Ds by their names, making the body nonpartisan in a formal sense, but that does not strip it of its deep political nature. (Too many people use the word “political” to mean “overtly partisan” which is gross inaccuracy).

A stripped-down definition of “political” would include the exercise of power over people. SCOTUS rulings do just that–some more than others, to be sure, but the notion that the Court is not inherently political is absurd.

Of course, part of the mythology that the Court is not political is that Justices are guided by “legal philosophies and theories” and not, you know, dirty ol’ politics. First, any theory of constitutional interpretation is a manifestation of politics, insofar as a given approach influences the types of authoritative decisions that are made. Second, it is unlikely that a given person’s view of the constitution was developed in a vacuum (although certainly a given person’s view will hopefully have been influenced by instruction learning, and intellectual examination of the subject material).

Beyond any of that, the nomination process is utterly and totally political. The president, an elected official with a specific political philosophy with electoral considerations (e.g., their own re-election or their party’s victory) makes the choice and then asks the Senate, a body populated with elected officials with specific political philosophies obsessed with re-election and majority status in the chamber, to confirm.

It is a parade of politics. Hence all the caring about the outcome.

Further, I would note that presidential candidates, for decades, have promised to appoint certain kinds of persons to the bench–especially as it pertains to the abortion issue. When candidate Trump said in 2016, “I will appoint — judges that will be pro-life, yes” that was a limitation, based on politics, of the pool he would dip into to make appointments. It was not a commitment to appoint “the best” or “the most qualified” but no one blinks at such statements (ditto when Democrats say the opposite).**** And we know, whether anyone says anything or not, that there is a pool from which Democratic presidents will pull and another from which Republicans will pull. Those pools are not about resume lines, but about presumed influence over outcomes.

To quote myself:

The mythology of American politics is that courts, especially SCOTUS, are run by sages who transcend basic politics and settle things based on well-developed legal theories. This is certainly the way the Court is usually talked about in the press (and often here at OTB). But, the more one pays attention, the more it seems that the Court is what it is often accused of being: a group of partisan-influenced individuals who are not as sagelike as many, themselves included, like to think.

Shockingly, political considerations go into political decisions. And even arguments over “the best” and “most qualified” are influenced by, you guessed it, politics.

*Note that Tom Brady is objectively the most successful QB of all time as measured in a number of objective categories (such as Super Bowl rings). He is arguably the GOAT. However, 22ish years ago, the assessment of a lot of experts who supposedly knew who The Best College QBs were at the time assessed him as not worth picking. New England chose him in the 6th round (and as a compensatory pick at that–the 199th pick and the 7th QB picked). I would argue that the evaluation of football talent is more objective than assessing judicial nominees, but even then there are plenty of very serious and certain people who get that wrong all the time.

**There is a whole other conversation to be had, but that there is no space for here, on the positive and the negative of “meritocracy.” I just want to acknowledge this issue at the moment.

***Another argument for expanding SCOTUS is that would allow more slots for better representation

****For the sake of time, I won’t pull more quotes, but this is a real situation in which, without any doubt “both sides do it.”

One idea I saw a while back was to stop nominating SCOTUS justices at all. Every year, 18 random appeals court justices will be selected: nine will select cases to be heard next year (without knowing in advance who will hearing them) and nine will hear the cases selected for review the previous year.

The idea that there is an objectively “most qualified” candidate for anything but a foot race is laughable. When making hires or appointments you take into account the gaps in your current team, present day needs, future needs, the personalities of others and on and on and on. The current Supreme Court line up comes from an incredibly narrow set of life experiences. Oh, they may have varied a bit as children and teenagers but by the time they were sixteen they were fast tracked into the establishment, and the elite of the establishment at that. This crew, Breyer included but Sotomayor and Thomas somewhat excepted, lack a breadth of experience corresponding to the breadth and seriousness of the cases coming before them.

Anyone (not wishing to make this about Sen. Collins specifically) criticizing Biden’s choice as politicized by comparing it to choices made by FG is just ROFLMAO funny. I’m sorry, but it is.

I wonder if Ms. Collins ever expressed the concern that a promise to select only Federalist Society recommended judges was in any way limiting?

As a former Supreme Court (Canada version) clerk, I can promise that there are a lot better legal minds than many Supreme Court judges. And even the really smart ones can be pretty shallow in their experience. Some legal problems just aren’t abstract.

Such a great post, Steven. As someone who loves a good footnote, I especially appreciated your point about Brady. Nicholas Grossman had made a similar point that if it was that easy to predict the best performer what would be the point of most fantasy sports leagues (or perhaps sports in general).

It’s so good I had to repeat it.

I also fear that every time one of us who writes publicly on this topic needs to defend her impeccable credentials, we’re (without realizing it) only helping to reinforce this implicit bias.

I think it’s actually pretty simple:

Political appointments are inherently political and operate under rules that do not apply to any other situation – because they are political.

Biden decided, before he was even President, that he would choose black women for the Supreme Court. By that declaration, he de facto excluded 93% of the prospective candidate pool if your metric is the US population and 97%+ of the prospective pool if your metric is lawyers (because lawyers are mostly white).

The attempts to deflect arguments about “best” do not apply because this choice, like most political appointments, isn’t about identifying objective metrics and evaluating candidates against those metrics. Instead, it’s about fulfilling political goals, hence why we call these political appointments.

For Biden, he didn’t choose to promise a black woman out of thin air – it was a political promise designed to appeal to his most important constituency – black Americans. If his main political constituency was South Asians instead of African Americans then Srinivasan would likely be the frontrunner and some other pundit would be complaining that Jackson isn’t getting any consideration because she has the wrong ethnicity or skin color. Nothing about this has anything to do with what is objectively ‘best” because race and gender aren’t metrics where there is a “best.”

Now, I don’t have a problem with this, but one can’t avoid the obvious – and legitimate – arguments that can be made about limiting the candidate pool based on physical aspects that a person was born with. You can’t dance around that pin.

So this, I think, is just wrong as an analogy:

The fact is that in any context except for a political appointment, limiting the candidate pool based on race and gender would be illegal. Being black vs being any other race and being a woman vs being any other gender is – to most people – not remotely similar to having a BA vs having a GED. And I’m sure, as a Dean, if you were to advertise for a new faculty position that you would be put in your place immediately if you attempted to limit candidates based on racial or gender criteria.

By the same token, the sports analogies do not work largely for the same reasons. Yes, it’s true that teams do not know how great or bad rookies will be (as the Tom Brady example shows) but that example is not remotely analogous to choosing a SCOTUS candidate. Football teams do not preemptively limit the candidate pool for QB’s much less by race and gender. Sports teams do the opposite – they try to widen the talent pool to find more prospects who might become greats.

So this is why political appointments are fundamentally different than the examples you’ve given. The normal rules do not apply to political appointments. Finding “the best” in some objective sense is a secondary concern when it comes to political appointments. Therefore, the “best” candidate for Biden to select is a black woman because he made a political promise to select a black woman.

The bottom line is that when it comes to political appointments Presidents can select who they want and they can use any criteria they want, even criteria that would be illegal in any other context. And that’s OK! That isn’t a criticism of Biden or the system, it’s just an acknowledgment of reality.

And the other side of that coin is that people can disagree with the political criteria a President makes. And there are people who actually do want SCOTUS candidates picked on the basis of a fair neutral evaluation of objective criteria and not on the basis of political factors. There is nothing wrong with that such disagreements are entirely legitimate. At the end of the day, however, the President gets to decide.

And, just so I’m clear, I’ll add this throat-clearing – I don’t have any problem with Biden limiting his pool to black women (my opinion might be different if I were a viable candidate who was eliminated from consideration because of physical aspects I have no control over). I think whoever Biden picks will almost certainly be sufficiently qualified to be on the court, and the Senate should be deferential to his choice absent some actual evidence that the candidate is compromised, or otherwise of questionable character.

@Andy:

This is basically my take. There is a subset of the legal profession (into which I most decidedly do not include myself) which, by virtue of a variety of factors (depth & breadth of experience, demonstrated intellect, substantial background in Constitutional law, service as a federal judge at least at the District, and ideally the Appellate level, etc.) who I’d consider to be qualified to serve on the Supreme Court. It’s a small set, but more and more it’s also a diverse set. I suppose its members could be ranked, if one wanted to get silly, but membership in the set itself implies that a member is a suitable choice.

If someone wants to go further and say “I only want African-American women from that set” or “Only Asian -Americans from that set please”, no skin off of my knuckles. Make the choice and the court will be just fine. The problem comes into play if/when it ventures off into “I want [set of characteristics, be they racial, ethnic, whatever], and their actual qualifications / suitability for the court are secondary to achieving that want”, then we start to run into problems. The process of selection really has to start with “list of suitable choices”.

I’m reminded of how shortly after Sonia Sotomayor was confirmed, she appeared on an episode of Sesame Street and one of the segments involved her talking with Abby Cradabby who, at the start of the segment was pretending to be a princess, and after talking to Sotomayor, Abby decided she wanted to be a supreme court justice instead.

The reason I remember because there was a brutally hilarious Colbert bit on the segment based around pointing out that (at the time) there had been more than twice as many American women throughout the country’s history who had married princes as there were American women who had become supreme court justices, so wanting to become a princess was actually a more realistic career goal.

@Pylon

You are probably aware of the old law school adage (at least here in the U.S.): A students become law professors, B students become judges, and C students become rich.

@Andy:

To clarify: that was not intended as analogy, it was intended as an example of an objective criterion and then to note that note all criteria are objective, especially when determining the “best” candidate.

I would note that my post was about the quest for the “best” or “most qualified” candidate–not a justification of picking based on race.

I am underscoring that criticizing using diversity as a criterion because it precludes choosing “the best candidate” is flawed because knowing who the best is is not at knowable as those critics argue.

The point of the sports example was simply to point out that it is not as easy as many claim to know, even based on a set of clear standard, who the best will be.

This fits with @HarvardLaw92‘s point above:

I would add that picking the best from that pool requires some serious subjectivity.

And let me address this:

First, as you note, political appointments and open searches for jobs are not* the same things. Still, while one is not going to advertise solely for a specific race or gender, it is not at all unusual for advertisements for professorial positions to encourage the application of minority candidates and I have seen any number of positions for administration positions (e.g., Dean, Provost) be classified as specifically being a “diversity” position.

I was trying to underscore that there is a massive amount of subjectivity to be associated with the notion of picking the “the best” or “most qualified” nominee. I also wanted to underscore that when it comes to whether a given president will pick “the best” or “most qualified” candidate, we do not have a national conversation about qualifications because of the maleness or whiteness of the candidate, but we always have conversations about whether the non-white, non-male candidate is, in fact, the most qualified choice because of their non-maleness and/or non-whiteness.

I don’t recall, but I am sure someone, somewhere questioned whether Brett Kavanaugh or Neil Gorsuch was the most qualified, but that question was not asked because he was a white male. And it certainly was not a massive national conversation.

*Edited to place a missing “not” into the mix.

@Andy:

BTW–I think you are missing my point here (or, I was unclear). I was addressing the criticisms of the choice and the fact that whenever a minority nominee is chosen, the criticisms that “the best” or “most qualified” wasn’t picked because of tokenism.

Rather clearly, the choice Biden will make will be political (as was his pledge).

@HarvardLaw92:

Two builds off this point:

1. Based on FoxNews reporting, this was a deeply political choice (not saying this in a derogatory fashion) that was wrangled out of Biden by James Clyburn, in return for his support ahead of the critical South Carolina primary. We will never know if Biden would have won the primary without Clyburn’s support or is a more milktoast commitment would have satisfied Clyburn. However, the win in South Carolina was a critical turning point for Biden and the decision needs to be considered in that context.

More on that reporting: https://www.foxnews.com/politics/clyburn-confirms-he-urged-biden-nominate-black-woman-supreme-court-floats-possible-candidate

To your second point:

I think part of the issue Steven and I take with this position is that unless you are microtargeting that initial pool or picking a group that is still struggling for proportional representation (let’s say “trans” as a whole without other points of intersectionality) the pools of current candidates are sufficient enough to have quality people who can meet the overall goal of “qualified.”

Whether intentionally or unintentionally, the use of “affirmative action” by Collins and others begins from a premise that said group doesn’t (and potentially couldn’t) contain equally qualified candidates.

@Steven L. Taylor:

This goes beyond academia. At Code for America, we explicitly encourage people with lived experience with the systems we are working to improve to apply for positions. And this is considered in our vetting process.

To be clear, BIPOC folks are not the only people who have experience in using the social safety net or interacted with the Criminal Legal System (the latter had definitely touched my extended family). But given their disproportionately high interactions with those systems, it definitely helps bring in a more diverse set of candidates.

And I completely agree with your hiring point.

This, this, this.

@Matt Bernius: FYI: I meant to say “political appointments and open searches for jobs are not the same things”

@Steven L. Taylor:

Ah… got it.

Though I would advocate that “not” might be a little too strong. In my experience, there is a lot of overlap in those Venn diagrams. I’ve been in enough organizations–large & small, public, private, academic, and non-profit–to completely discount the amount of politics that come into play with (a) opening a hiring line, and (b) candidate selection.

It’s just in many cases with hiring, the politics are far more conceal than in political appointments.

@Matt Bernius: What I mean is: for a political appointment at a high level, the person making the appointment has more leeway and is typically not sending out an invitation for applicants. While in a hiring process there is supposed to be a more open invitation for persons to apply and the hiring authority has less leeway.

I do agree with this.

I mean, Andy is correct: I can’t say we are only going to hire a Black female for the next Physics opening, but Biden can say that for SCOTUS.

@HarvardLaw92: Service on the U.S. Courts of Appeal appears to be the gold standard for appointment to the Supreme Court. Despite its popularity it’s not a standard that I feel is very useful.

Federal judgeships along with the U.S. Attorneys are the most political of all federal jobs. Candidates for the Federal bench come almost exclusively from the local political machine, who generally have been active in party politics. They also, more often than not come from white shoe law firms without a lot of litigation experience.

I have tried hundreds of cases in a dozen different states and have argued in five of the Circuit Courts of Appeal. Very seldom have I appeared before a judge who I believed merited appointment to the Supreme Court. I would prefer to see the appointee be one with real world trial experience. RBG and Thurgood Marshall, both of whom came to the bench with years of trial experience fighting for their clients are the model I prefer. I would love to see for once a candidate for the Supreme Court who had sat with his client, as I have, on death row hoping for a lastminute stay. (It came with less than thirty minutes to spare). One reason I agree with HL’s preferred candidate for the job is her experience as a public defender. She knows what it’s like to face the might of the U.S. Government.

@Matt Bernius:

Of course it’s a deeply political choice. That having been said, the roster of potential candidates who I’d consider to be suitable to sit on the court and still fulfill his political goals in making the choice is deep enough to permit both aims to be satisfied. Indeed, it really only needs to have a depth of one to get there. Luckily (or not, depending on whether one of the candidates is a friend and you’d cheerfully eliminate all of the others on that basis alone), it’s several women deep.

@a country lawyer:

I won’t disagree with that. I should have been more explicit with regard to what I was encompassing in “depth & breadth of experience”. That term absolutely ideally includes substantial experience as a litigator. Even more ideally it includes substantial, or at least materially meaningful, experience on both the prosecution and defense sides of criminal process. My aim there, when including it with district / circuit experience as a sitting judge, was that I want to see candidates for the court who have spent substantial time on both sides of the courtroom equation. Justices arriving at the court really shouldn’t need a remedial course in anything / time to figure out things that they’ve been sparingly, if at all, exposed to. Least of all those being litigation …

@a country lawyer:

Forgot to add – I won’t disagree with you either that the bulk of the federal bench has no business being anywhere near the court, but I do believe that potential nominees should have served there. The number of people who will ever serve on the court is so minuscule in relation to the size of the broader federal judiciary that we can afford to keep it on the list as a “want to have” while still excluding the ones who obviously don’t merit a nomination.

@HarvardLaw92: One benefit of selecting Supreme Court nominees from the Federal bench is being able to read their written opinions to judge their abilities and legal leanings. Although published opinions are frequently written in whole or part by the judges’ clerks it does provide a window in predicting how they may rule if nominated and confirmed.

@Steven L. Taylor:

and

and

“Best” depends on what criteria one chooses and then how one evaluates the criteria. And for Biden, the primary is the race and gender of the candidate. He used that criteria to narrow down the pool by eliminating anyone who didn’t meet that racial and gender test. And since Biden still has several potential candidates after reducing the pool, he will have to develop more criteria and further evaluate candidates on those to determine which one is “best” out of that more limited pool.

So choosing the “best” candidate is not “flawed” – it’s unavoidable.

The obvious and relevant difference is that no one came out and preemptively said only white males would be considered. Instead, for GoP nominations, the primary exclusionary criterion is the endorsement by the federalist society. For Biden it was race and gender.

They, too, were looking for the “best” candidate, just as Biden is doing. The only difference is the criteria they used.

@Andy:

That was rather a substantial part of the point of the post.

Yet, that doesn’t stop the fantasy that many appear to hold to that there is a best choice to make (it happens with every nomination).

And, to another point I thought I made: it is problematic, to be kind, to bemoan (as many critics do) that picking for diversity means not picking “the best.”

I am sure that I have failed to be as clear as I could in the above, but I also think that you are reading the post with some preconceived notion of what I am arguing.

Indeed.

Indeed. But the media discourse, nor even Democratic attacks, accuse the GOP of not picking the “best” or “most qualified” when a Federalist endorsed nominee is picked. But they frequently do when a Dem nominates a minority (see the Ilya Shapiro tweet as a recent example).

@a country lawyer:

Agreed on all of the posted!

That’s definitely the case here in the Western District of NY.

That, interestingly is not as much the case here. Granted the number of white shoe firms we have tends to be a lot fewer in Rochester and Buffalo than in NYC. Most folks that I can think of came from City and County judgeships (usually, though not always, bringing their county clerks with them… which can have mixed results).

I expect things are different in the Southern District.

100%… though I’d prefer more “real-world trial experience” NOT on the prosecution side. It still feels that, in areas like mine, the US Attorney’s office is a good route to a federal judgeship (even if it’s a magistrate one).

@Steven L. Taylor:

and

The point I think you are missing here is that these critics have a different definition of what is best. And they, unsurprisingly, think that prioritizing other criteria (like race/gender) over the criteria focus on will not result in finding the “best” candidate.

Secondly, “best” isn’t a fantasy. Everyone thinks there is a “best” choice, the only difference is the criteria used to determine what is best. Change the criteria, and that changes who will be best.

The debate here is really about what criteria should be used to select candidates for the Supreme Court. And people who believe that race and gender should not be exclusionary factors or who think they should be less important factors are not wrong. They aren’t engaging in a “fantasy” – they simply have a different opinion about how to define “best.”

And Biden is no different. He’s looking for the best candidate too and the best candidate for him has defined racial and gender characteristics who also meets other criteria.

@Andy:

Well, yes, but with some major caveats.

If we all agree that your best, my best, and their best are all different, and that’s ok, then we are in agreement.

But, there clearly people who believe that best is an objective category, and therefore their best really is better than my best or your best. I do think that there is a mythology around SCOTUS in particular on this count.

Worse, however, is that I think that many people weaponize the rhetoric of picking the “best” when it comes to any kind of consideration of diversity as a criterion.

@Steven L. Taylor:

I do not see this mythology as limited to SCOTUS – in my view the debate over the “best” WRT SCOTUS nominations follows the same tune as the debate over the “best” Presidential candidate in a primary. In sports this same dynamic is in play for competition for the limited number of hall-of-fame slots every year. A lot of players deserve it, but there are only so many slots and lots of people have strong and conflicting opinions.

Maybe, but in this case, I think the objections are not about opposition to diversity generally but the fact that Biden skipped ahead. By focusing only on black women, he excluded many people who would also have brought just as much racial and gender diversity to the court. And people who had favorites from other diversity categories were understandably upset that their preferred pick would not even be considered.