American Public Strongly Supports Statehood For Puerto Rico

In contrast to the idea of granting statehood to the District of Columbia, the American public appears to strongly support statehood for Puerto RIco.

In sharp contrast to public opinion regarding statehood for the District of Columbia, a new poll indicates that most Americans support statehood for Puerto Rico:

Two in three Americans support statehood for the island of Puerto Rico, according to a Gallup Poll released Thursday morning.

The 66 percent support for admitting the island as the 51st state is consistent with polling dating to the early 1960s. Support is highest among Democrats, younger voters, and nonwhite voters. But while nearly half of Republicans also back the proposal, the party’s leaders do not.

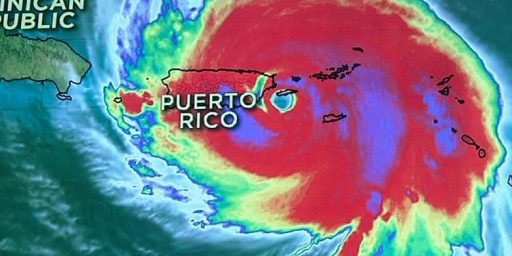

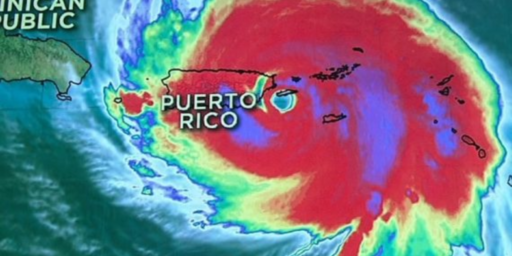

resident Donald Trump, who has disparaged Puerto Rico’s leadership and faced criticism for the federal government’s slow response to devastating Hurricane Maria, has said he is an “absolute no” on Puerto Rico statehood. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell recently said granting the island statehood and full representation in Congress would be “full-bore socialism.”

The high level of public support for Puerto Rico statehood stands in stark contrast to the public’s overwhelmingly negative views on statehood for Washington, D.C., which most voters, including most Democrats, said they oppose in another recent Gallup Poll, and comes as political and legal turmoil rocks Puerto Rico.

More directly from Gallup:

Two in three Americans (66%) in a June Gallup survey said they favor admitting Puerto Rico, now a U.S. territory, as a U.S. state. This is consistent with the 59% to 65% range of public support Gallup has recorded for Puerto Rico statehood since 1962.

While still a minority, the 27% who oppose making Puerto Rico a state is up slightly from the prior three readings, while the 7% with no opinion is relatively low.

Americans’ current support for Puerto Rico statehood stands in contrast to their opposition to admitting Washington, D.C., into the union, which they oppose by about a 2-to-1 margin.

The U.S. annexed Puerto Rico in 1898, at the conclusion of the Spanish-American War. In the century that followed, Congress granted the island certain autonomies, and Puerto Rico currently functions in many ways like a U.S. state. But there are key differences between its status and those of the 50 U.S. states, including that residents of Puerto Rico do not pay federal income tax and cannot vote in U.S. general presidential elections.

At the ballot box, Puerto Ricans have supported statehood in referendums conducted over the past decade. For example, 97% of voters cast their ballots in favor of statehood in 2017. However, the low 23% turnout rate in the 2017 referendum has given statehood opponents ammunition to cast doubt on the vote’s legitimacy, particularly because leaders opposed to statehood urged their sympathizers to boycott the election.

(…)

Majorities across key subgroups favor making Puerto Rico a U.S. state, with higher support among Democrats (83%), adults aged 18 to 29 (80%) and nonwhites (74%).

Republicans are mixed on the question of statehood for Puerto Rico, with 45% favoring statehood and 48% opposed. Just before Gallup put this latest poll into the field, Republican Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell said that admitting Puerto Rico and Washington, D.C., as U.S. states would amount to “full-bore socialism” because of the consequences of adding four Democratic senators to the U.S. Senate. Recent efforts to make Puerto Rico the 51st state, however, have garnered considerable congressional Republican support — and the politician representing the island in the U.S. House of Representatives is a Republican herself. And though President Donald Trump has said he is an “absolute no” on Puerto Rico statehood, the four previous Republican presidents — from Gerald Ford to George W. Bush — have supported or have expressed support for statehood for Puerto Rico.

As Gallup goes on to note, though, the likelihood of the island Commonwealth achieving statehood anytime soon is complicated by politics in both San Juan and Washington:

What complicates the territory’s path to statehood now is not U.S. public opposition, but rather a series of political events that have unfolded both in San Juan and in Washington.

In San Juan, the governor’s committed push for statehood may now be jeopardized by scandals within his administration, which have led to thousands of residents protesting outside the governor’s mansion, calling on him to resign. And if the mayor of San Juan defeats him in the 2020 gubernatorial election, her anti-statehood platform may put a stop to further statehood efforts.

Meanwhile, in Washington, any efforts to make Puerto Rico a state will find opposition in the U.S. Senate leadership and in the White House, where Trump maintains a running feud with some of the island’s politicians over their criticisms of the federal government’s handling of the response to Hurricane Maria.

The issue of statehood for Puerto Rico is one that has been heavily debated, and voted on, both in the mainland United States and on the island Commonwealth for the better part of a decade now. Among Americans as a whole. the idea of Puerto Rican statehood is one that a majority of Americans have supported for some time now, although there has been something of a divide along party lines. Generally speaking, self-identified Democrats and independents have been more supportive of the idea than Republicans. In part, this is due to the realization among Republicans that allowing statehood would likely be of more benefit to Democrats on Capitol Hill than it would be to Republicans. This is especially true with regard to the Senate since it is expected that Democrats would be more likely to win the island’s two seats than Republicans. Because of that, some proposals for Puerto Rican statehood have been accompanied by a proposal for statehood for the U.S. Virgin Islands, which many believe would be more likely to elect Senators that would ally with the Republican Party. Despite that, as the poll indicates, a plurality of self-identified Republicans support statehood.

On the island, the issue has been somewhat more complicated and played itself out in a series of referenda over the past forty years. As the list below indicates, public opinion on the question has shifted but it does seem as though statehood is the most favored option among citizens of the island at this time:

- The first such referendum, which took place in 1967, asked voters to choose between maintaining the island’s status as a Commonwealth of the United States, statehood, and independence. In that vote, the majority vote (60.4%) went to maintaining Commonwealth status. Statehood came in second with 39% of the vote, and independence came in a distant third with less than 1% support.

- A second referendum took place some 26 years later in 1993. In that referendum, the pro-Commonwealth side was again victorious but the margin was far smaller than it had been the last time. Specifically, 48.9% of voters voted for the option to maintain Commonwealth status, 46.6% voted for statehood, and 4.6% voted for independence.

- In 1998, a third referendum was held that asked voters to choose between Commonwealth state, statehood, independence, an ill-defined option called “free association,” and “None of the above.” In that referendum, “None of the above” garnered a bare majority of the vote with 50.5%, followed by 46.6% choosing statehood, 2.6% choosing independence, and less than 1% support for “free association” and maintaining Commonwealth status.

- The next referendum came in 2012 and involved two questions being posed to the electorate. The first question was a simple “yes” or “no” question that asked if the island should maintain its current status as a Commonwealth. On that question, a majority (53.97%) answered “No” compared to a “Yes” vote of 46.03%. The second question asked voters to choose between the various option, and in that vote statehood captured a majority (61.16%) followed by “Free Association” at 33.49% and independence at 5.49%. Given the result of the first question, maintaining Commonwealth status was not among the options presented. Finally, the most recent referendum took place in 2017 and, at least on its face, showed overwhelming support for statehood (97.18%) with all other options below 2%. The results of this last referendum is in doubt, though, because the vote was heavily boycotted due to political disputes among the island’s political parties. In the end, only about 22.9% of the island’s eligible voters voted. This is the lowest turnout for any of the status referenda.

Despite apparent public support on the mainland for statehood, Congress is not likely to act or express any interest in granting Puerto Rico statehood any time in the near future. Part of the reason for this, of course, is political and rooted in the fact that any Congressional and Senate representation that a “State of Puerto Rico” would send to Washington would be overwhelmingly Democratic. This isn’t an unusual response to statehood petitions that Congress has received over the past two centuries. On more than one occasions, political forces in Washington were able to successfully block statehood applications based on the fact that the proposed state would result in one major party or the other benefiting from the addition to the Union. Additionally, there have been more than one example of two states being admitted at roughly the same time. The most notable times this happened, of course, was in the 19th Century when the statehood applications of several states were complicated by the issue of the expansion of slavery. This resulted in laws such as the Missouri Compromise and the Kansas-Nebraska Act. There were also political motivations behind the admission of Alaska and Hawaii in 1959. In addition to the political concerns, the current financial status of Puerto Rico makes the admission of the island as a state unlikely for the time being. As it stands, Puerto Rico already receives considerable financial assistance from the Federal Government. Statehood would increase that significantly, as would the fact that the combination of Puerto Rican representation in Congress would likely combine with representatives from states with large Puerto Rican populations to push through increased aid to the island.

The interesting question is how one explains the significant differences between public support for statehood for the District of Columbia and statehood for Puerto Rico. One possibility, of course, is that Puerto Rican statehood is an issue that has been on the table for more than fifty years whereas D.C. statehood is one that only really comes up when Democrats have control of all or part of Congress. Another possibility is the fact that the American public is simply more likely to support statehood for the territorially larger and more populated island than it is for Washington D.C., which is currently the nation’s 20th most populated city. Finally, it may simply be that the public sees more merit in the idea of statehood for Puerto Rico than it does statehood for a city that has fewer residents than cities such as Jacksonville, Florida, Austin, Texas, Columbus, Ohio, and Indianapolis, Indiana.

Be that as it may, because of political considerations statehood for Puerto Rico seems to be no more likely than it is for Washington, D.C.

That might eventually be true, but PR has its own political parties which presumably would compete for the Congressional and Senate seats. As far as I’m aware, neither the Democratic or Republican parties have much of any actual influence in PR. It would definitely be interesting to see how that would evolve politically over time.

Part of the difference is that there are Puerto Rican communities in other states advocate for the island even though they no longer live there. There’s no corresponding “Districtian” cultural group to advocate for DC residents outside of DC.

@Stormy Dragon:

Now I’m mentally picturing a New Yorker going, “Hey, have you ever been to Little DC? It’s the only place to go if you want really authentic bean soup in this city.”

@Stormy Dragon: I wonder how much of the vote on statehood for DC has been warped by the transient nature of a lot of the population, coupled with the typical distaste for lobbyists and politicians?

Not many people care about the rest of the DC people–the heavily minority poor who are just trying to deal with the local incompetent bureaucrats. (I have stories….grrr…) The rich either don’t live in DC itself or have enough clout to cut through all the minuscule petty-power antics at the DMV and tax offices. So it’s the poor dumb bastards who can’t move and have no power who are stuck with putting up with the snafu officialdom that is daily life in DC.

(Huh. This was supposed to be on the DC thread. Oops.)

With a post-Maria population of ~3.1 million, PR would get 4-5 Congressmen (and 2 Senators). With the number capped at 435 this means other states would be loosing seats (with HI and AK it went to 437 until after the next Census and reapportionment – or the cap could be changed). CA and MN (most likely to be at the tipping point based on 2020 projections) and other states won’t like hearing that.

We shouldn’t be in the colonizing business. Either statehood or independence is fine, but not the “ruled by the US, but without a vote” status quo. Guam and other territories should also be either made states or set free.

Ruling people, without giving them a say in the Federal government, is Un-American. Antithetical to our values as a country. Literally what the Founding Fathers revolted against.

And, if the people of these lands really want to be living in colonies, ruled from afar, well, perhaps Great Britain would enjoy having a few colonies again.

——

Remember when Obama was criticized as being “anti-colonial”? Good times, good times.

@Richard Gardner:

Which gets to the problem with the cap. Honestly, I wish the Democrats would damn the torpedoes and advance a law to change the cap (and move it away from being a law that requires approval from the Senate and the executive to enact).

Interestingly, Puerto Rican statehood was long a policy plank for the Republican Party.

I’m sympathetic to @Gustopher‘s position on the territories but tend to support independence vice statehood. I can’t offhand think of a good reason to add non-contiguous states, particularly ones consisting of people who aren’t American other than by happenstance. They have unique cultures, languages, etc.

@Gustopher:

The people of Puerto Rico have the right of self-determination and if they want to change their political status, they will make the effort to do so. So far they do not seem to think it’s that big of a deal since they haven’t put much effort into either alternative. As long as that is the case the federal government should do nothing.

Puerto Rico is long overdue in becoming a U.S. State. #MakePuertoRicoAStateNOW

Let that sink in for a moment. Think about what Mitch could actually mean by that.

What a contemptible excuse for a human being.

@James Joyner:

So, James, who exactly is it that you think is American other than by happenstance? Got a lot of Native American friends?

Think carefully about just what it is that you think ‘American’ means.

@Andy:

It cheapens *us* and it weakens *our* institutions to have a large number of second class citizens. They might be happy with the arrangement, but it’s not all about them.

Look at @James Joyner’s comment — he doesn’t see these people (these American Citizens) as being, well, American.

I don’t think that he would want to let thousands die after a hurricane, but it’s a teeny-tiny version of the mindset that does allow people to let thousands die after a hurricane. We take care of our own, and they’re not *quite* our own.

If Puerto Rico is a state, then they are American.

If they are independent, they are their thing, and we will help our neighbors where we can, but the priorities are clear.

@DrDaveT:

Recognizing rights to others = socialism in the Republican mind.

@DrDaveT: @Gustopher:

The aboriginal peoples weren’t American in the sense I’m using it, they were Cherokee, Navajo, or whathaveyou. The United States was created by former British subjects who colonized their lands and, over time, developed a sense of uniqueness and fought to create an independent nation with a particular ethos founded in the Enlightenment.

Over time, we absorbed immigrants from all over Europe, Asia, etc. And, of course, imported massive numbers of African slaves. They became American, eventually, by adapting to our culture and language—and also adding to it.

There are plenty of Americans with Puerto Rican ancestry. But the people of Puerto Rico, like the people of Guam, American Samoa, and other territories see themselves first and foremost as Puerto Rican, Guamanian, and Samoan. Six decades in, that’s probably true of Hawaiians.

My teaching partner last year, a Marine Infantry lieutenant colonel, is Guamanian. Ditto a fellow lieutenant during my Army days. They’re certainly Americans, having moved to the mainland and joined our society. But most of those back home are citizens because we colonized their homeland but don’t think of themselves as “Americans.”

@Gustopher:

My point is that we shouldn’t dictate to the Puerto Rican people what their political status should be, especially if it’s something that is pretty much irreversible, like becoming a state. It’s up to them to take the lead – if that’s what they want. It’s not America’s responsibility to make such choices for them.

@James Joyner:

I want to tread softly here, because this is a topic where it would be easy to unintentionally give offense, but some of what you are saying I find disturbing.

Certainly. At what point (if ever) did they become American, in your view?

Well, maybe. The founding fathers were not themselves the ones “who colonized their lands”, for the most part, and most of the other inhabitants of the British colonies (including a still fairly large percentage of aboriginal peoples) were not involved in fighting for independence or imposing an Enlightenment ethos.

Also, the British settlers colonized only a tiny fraction of the now-US. Many of those lands were colonized by the Spanish, the French, the Russians, various Scandinavians, Germans, etc. The new United States variously acquired those lands over time. Does that matter in your analysis of who/what is ‘American’?

Here’s where I start to get uneasy. When you say ‘we’, do you include people from the non-English traditions? Are you saying that the ones who did not adapt to the English language and English-derived culture did not, in fact, “become American”?

17 decades in, it’s still true of Texans — but I suspect that you think that’s different somehow. More importantly, are Hawaiians who think of themselves as Hawaiians not Americans, or not really Americans, in your view?

@DrDaveT: I admit this is fuzzy. I’m really talking the difference between a state and a nation and between citizenship and acculturation. And there are few bright lines.

Puerto Ricans, Guamanians, etc. are American citizens. Full stop. They’re entitled to the same sort of response from their government in the event of a natural disaster as those of Texas, California, or Kansas.

But Puerto Ricans living in Puerto Rico are not American in the same way that Puerto Ricans living in New York are. To use a somewhat silly example, they have their own Olympic team and root for it against the US Olympic team.

And, no, the same isn’t true of Texans. For a variety of reasons, Texans have an unusual degree of pride of place compared to, say, Virginians. There are a relative handful of secessionists who want to be shed of interference from the central government in Washington. But they’re overwhelmingly patriotic Americans who identify as Americans first and foremost.

The concept of American (and of white, for that matter) gradually evolved over time. It’s more inclusive now than ever. But, yes, I expect second-generation American citizens to be fully fluent in English and adapt to our folkways. And I expect their primary political loyalty to be this country, not their country of origin.

@James Joyner:

I understand the pragmatic arguments for a single official language (though it always leads to unequal treatment under the law in practice), but the latter needs clarification. Which folkways are ‘our’ folkways? Columbus Day? St. Patrick’s Day? Cinco de Mayo? Amish and Mennonite communities? Jazz? Pizza? Hamburgers and hot dogs? Highland games? Hannukah? How about Native American culture and beliefs?

None of the above? After all, none of those are English, or developed by Anglo-Americans. None of them look like assimilation.

@DrDaveT:

I’m not sure any of those much matter in terms of acculturation and buying into the American ethos. I don’t know that ones food or musical preferences really have much to do with how we get along as a people. It’s more about social coventions, habits of dress, courtesies, understandings of physical space, the appropriateness of private vs public conduct, and the like. And, frankly, we’ve diverged so much on many of those in recent years that they can frequently be a cause of friction.

The Amish and Mennonites are excellent examples of groups—and, handily, ones that are almost exclusively white—that are undeniably American in many senses but not really American because they’re just extreme outliers. Indeed, almost by design, they live apart from the rest of American society.

@James Joyner:

Allow me to suggest that “we’ve diverged” is a misinterpretation of “I have noticed that the norms I grew up thinking were universal turn out not to be.”

My favorite example is from a mandatory workplace training class my wife took a few years ago. The instructor stood at the front of the room and said “Raise your hand if a parent ever said to you ‘Look at me when I’m talking to you!'” All of the white people raised their hands. Then she said “Raise your hand if a parent ever said to you ‘Don’t you look at me when I’m talking to you!'”. All of the black people raised their hands.

Everyone in the room suddenly realized that there were times in the past when they had interpreted someone else’s body language and attitude exactly wrong without knowing it. Sheepishness prevailed, and a sudden willingness to take the course much more seriously.

I, for one, am not willing to say that one of those cultures is American (and normal, and correct) and the other isn’t. The extension to customs of dress, language use, personal space, etc. I leave as an exercise to the reader.

@DrDaveT:

I’m sure some of that’s true. But we’ve also had massive immigration and cultural change over the last four decades. But, yes, it’s more apparent in places like DC and Northern Virginia than in the Deep South.

But it’s not just that white/Northern European norms are being contrasted with those of other cultures. We’ve just generally decreased in conformity to broader social conduct that respects the fact that other people exist.