Time for a New Generation to Lead?

The Silents and Boomers have been in charge too long.

American Enterprise Institute senior fellow Yuval Levin takes to the NYT to ask, “Why Are We Still Governed by Baby Boomers and the Remarkably Old?“* It’s a familiar concern that we’ve discussed here many times over the years. Rather than rehashing the standard concerns about dementia, though, Levin takes a different tack.

Bill Clinton, George W. Bush and Donald Trump, whose presidencies spanned more than a quarter-century, were all born roughly within two months of one another in the summer of 1946. Nancy Pelosi has been the Democratic leader in the House for almost 20 years. Mitch McConnell has led Senate Republicans for about 15 years. Our politics has been largely in the hands of people born in the 1940s or early ’50s for a generation.

Indeed, as I’ve noted before, Joe Biden is four years older than Clinton, Bush, and Trump—and almost 20 years older than Barack Obama, whom he served as Vice President. And Clinton was elected 30 years ago.

But, again, Levin’s concern is about worldview, not infirmity:

We should wish them all many more healthy years and be grateful for their long service. But we should also recognize the costs of their grip not only on American self-government but even on the country’s self-conception.

It’s often said that Americans now lack a unifying narrative. But maybe we actually have such a narrative, only it’s organized around the life arc of the older baby boomers, and it just isn’t serving us well anymore.

How so?

Consider what the country’s modern history looks like from the vantage point of an American born near the beginning of the postwar baby boom. Say you were born the same year as Mr. Clinton, Mr. Bush and Mr. Trump, in 1946. Your earliest memories begin around 1950, and you recall the ’50s through the eyes of a child as a simple time of stability and wholesome values. You were a teenager in the early ’60s, and view that time through a lens of youthful idealism, rebellion and growing cultural self-confidence.

By the late 1960s and into the ’70s, as a 20-something entering the adult world, you found that confidence shaken. Idealism gave way to some cynicism about the potential for change, everything felt unsettled and the future seemed ominous and ambiguous. But by the 1980s, when you were in your 30s and early 40s, things had started settling down. Your work had some direction, you were building a family and concerns about mortgage payments largely replaced an ambition to transform the world.

By the 1990s, in your 40s and early 50s, you were comfortable and confident. It was finally your generation’s chance to take charge, and it looked to be working out.

As the 21st century dawned, you were still near the peak of your powers and earnings, but gradually peering over the hill toward old age. You soon found the 2000s filled with unexpected dangers and unfamiliar forces. The world was becoming less and less your own.

You reached retirement age in the 2010s amid growing uncertainty and instability. The culture was increasingly bewildering, and the economy seemed awfully insecure. The extraordinary blend of circumstances that defined the world of your youth seemed likely to be denied to your grandchildren. By now, it all feels that it’s spinning out of control. Is the chaotic, transformed country around you still the glittering land of your youth?

This portrait of changing attitudes is, of course, stylized for effect. But it offers the broad contours of how people often look at their world in different stages of life, yet also of how many Americans (and, crucially, not just the boomers) tend to understand our country’s postwar evolution. We see our history, and so ourselves, through the eyes of Americans now reaching their 80s.

As history, this narrative leaves a lot to be desired. But as a kind of pocket sociology of our time, it is utterly dominant.

The notion that all people of the same age cohort have the same worldview is, of course, untrue. To take an obvious example, Bill Clinton and Donald Trump see the world quite differently despite being born within weeks of one another. But the concept of “generations” has endured so long because there’s a certain truth in it. Being alive and impacted by events like the Great Depression, World War II, Vietnam, the Civil Rights movement, Watergate, or 9/11 affects how one views the world.

At 56, I’m well into middle age. My parents, both gone, were born about a year after Biden. They had no memory of the Depression or World War II. My dad served in Vietnam when I was very young but it seemed like some event in the distant past by the time I served in Desert Storm. Even though I was alive when Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, and Robert Kennedy were assassinated, the Civil Rights movement is something that happened in black and white, a long-ago historical event. Meanwhile, things that happened 30 years ago seem recent.

Almost every story we now tell ourselves about our country fits into some portion of the early-boomer life arc. And our politics is implicitly directed toward recapturing some part of the magic of the mid-20th-century America of boomer youth.

That moment — when many Americans trusted their leaders and went to church, when idealistic protests seemed to drive significant social change, when you didn’t need a college degree to get a union factory job that would let you support a family in the suburbs on one income — exerts an inexorable pull on our political imagination now. The parties blame each other for how far America has fallen from that standard, and politicians (old and young, left and right) implicitly promise a return to some facet of it.

There’s definitely something to this. Most of the proposed solutions to our ills seem aimed at bringing back some bygone era, whether it’s the 1970s or the 1950s. Why, we need to bring back manufacturing jobs and get everyone back into a labor union. Or send even more people to college, because that’s what we did after World War II and it worked then.

That time was not imaginary. But it was not so simple either, particularly for people at the margins of the powerful mainstream consensus of the age. And it was a singular period made possible by an unrepeatable set of circumstances in the wake of the Second World War. We do ourselves no favors when we treat it as the American norm, when we ignore its costs and challenges, or when we cling to its glamour by keeping the people who lived that story in power as they age.

Emerging from WWII, America was far and away the most powerful country on earth. Europe and Japan were pretty much destroyed by the war while we had four years of pent-up demand. And it was a very different country demographically. We had considerably less than half our current population and it was 90% white, 10% black, and essentially 0% everything else.

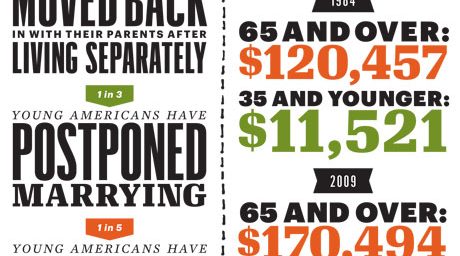

Our model of social change is still rooted in midcentury clichés. Younger Americans imagine that starting a family and owning a home was much easier for previous generations than it really was. They buy the broad outlines of the boomers’ nostalgia and take it to mean they are inheriting a desiccated society.

Confronting injustice, they almost unthinkingly re-enact the outward forms and symbols of college protests of the 1960s, generally to no effect. Our implicit definition of social cohesion takes for granted that midcentury moment, when America had not only been through a long stretch of intense mobilization in war and depression but was also less culturally diverse than at pretty much any time before or since.

Modern protest movements, whether Occupy Wall Street or Black Lives Matter, do seem to be aping the civil rights era. I’m not sure that’s the problem, though. Rather, the frustrations being voiced now are more diffuse and the solutions less clear. Removing legal barriers to Blacks voting, attending school, and otherwise participating in society is simply easier to understand and achieve than unfocused angst over income inequality or even more discrete outrage over police brutality. But Occupy, in particular, did seem rooted in a sense that going to college no longer magically puts one on a road to the upper-middle class.

Above all, though, our boomer sense of ourselves keeps us from orienting our society toward the future, and contributes to a broadly shared sense of despair about our country that is neither justified nor constructive. Our politics should prioritize planning for greater national strength in the medium term, but we can hardly expect quarreling octogenarians to have that future clearly in mind.

And yet, the solution is not youth politics either. In a new book on leadership, the former presidential adviser David Gergen is admirably frank in acknowledging that those born in the 1940s, like himself, should make room for new leaders. But he looks for them among the youngest Americans. “Millions of baby boomers and alumni of the Silent Generation are starting to leave the stage, to be replaced by millennials and Gen Zers,” he writes.

Maybe I take this personally, having just turned 45, but Mr. Gergen blithely skips over Americans born in the 1960s and ’70s. Maybe he can’t quite fathom middle-aged leadership. Yet middle-aged leadership may be exactly what we now require.

I’m a decade older than Levin but we’re both part of the so-called Generation X. And, yes, for whatever reason, we seem to be forgotten in all these analyses. “Boomer” is a synonym for old and “Millenial” is a synonym for young. We’re in between those and often skipped over. (And Biden and Pelosi are actually part of the pre-Boomer “Silent” generation.)

And, yes, it would seem to be our generation’s turn to run the country. Clinton was 46 when he became President in January 1992, representing a passage of the torch from the Greatest Generation to the Boomers. Obama was born in 1962, toward the tail end of the Boomer generation, should likely have been the last. Instead, we went back in time to a much older Boomer and then, shockingly, back again to the Silents. (Who, oddly, got skipped over as well when it was their turn.)

Many American institutions seem locked in battles between well-meaning but increasingly uncomprehending leaders in their 70s and a rising generation, in their 20s and early 30s, bent on culture war and politicization and seemingly unconcerned with institutional responsibilities. Our politics has the same problem — simultaneously overflowing with the vices of the young and the old, and so often falling into debates between people who behave as though the world will end tomorrow and those who think it started yesterday. The vacuum of middle-aged leadership is palpable.

There are some politicians of that middle generation — some members of Congress and governors, even our vice president. Yet they have not broken through as defining cultural figures and political forces. They have not made this moment their own, or found a way to loosen the grip of the postwar generation on the nation’s political imagination.

Again, that happened with the Silents at the Presidential level but they at least had Dick Gephardt, Pelosi, and others in prominent Congressional leadership posts.

A middle-aged mentality traditionally has its own vices. It can lack urgency, and at its worst it can be maddeningly immune to both hope and fear, which are essential spurs to action. But if our lot is always to choose among vices, wouldn’t the temperate sins of midlife serve us well just now?

Generational analyses are unavoidably sweeping and crude, and no one is simply a product of a birth cohort. But in our frenzied era, it’s worth looking for potential sources of stability and considering not only what we have too much of in America and should want to demolish and be rid of but also what we do not have enough of and should want to build up.

We plainly lack grounded, levelheaded, future-oriented leaders. And like it or not, that means we need a more middle-aged politics and culture.

To some extent, this reads like generational special-pleading. Then again, neither Levin nor myself are likely to be the next President or Speaker of the House.

Still, the norm since the founding of the Republic has been to elect Presidents to their first term when they are between 45 and 60. It’s been rare, indeed, to go much outside that range. Granting that we’re living and staying healthier longer than we used to, the fact that the current President is almost 80 halfway through his first term and the leading contenders to oppose or replace him are almost as old is unusual, to say the least.

_______________

*The print edition has the less evocative title “Why Are Boomers Still Governing?”

sigh…

Ok. What now?

And yet,

He proposes an unavoidably sweeping and crude “solution”.

I have long toyed with the idea of putting,

“Don’t Let Old Fs Like Me Decide Your Future

VOTE”

on the back of my truck, but the fact of the matter is us old Fs vote at a far higher rate than younger folks. After all, what else have we got to do on an early November Tuesday morning?

When it comes to old people being in all the leadership posts, I think that is a systemic thing and all the crying about how “younger politicians should be in the forefront” is the equivalent of “Young People Yelling at Clouds”.

Whether his argument can survive scrutiny or not is a question, but his premise, that our leadership is too d@mn old is right. From a governing perspective this is a particular problem for Dems as the leadership in House and Senate is aged, and if we go back to the 2020 campaign, three of the leading Dem candidates were over 70.

For R’s, it’s a problem in the Senate, but not the House, given caucus rules that term limit committee leadership posts, with that encouraging older members to retire or move on to other offices. Going back to the 2016 campaign and looking forward to 2024, except for the unique problem of TFG, potential R presidential candidates are younger.

@OzarkHillbilly:

I live in a vote by mail state. There is evidence that mail ballots have increased turnout somewhat across the board, there’s no evidence that it has increased young voter turnout any more than old voters.

@Sleeping Dog:

Give Newt credit for addressing a structural problem. A Paul Ryan, chairing both Budget and Ways & Means committees and then holding the Speakership, all before he turned 50, simply can’t happen on the Dem side.

@Michael Cain: Young folks have more pressing concerns weighing on their minds: Can I get laid? Gotta find some beer. The boss is gonna kill me if I’m late again.

Middle aged folks have more worries: After the mortgage, will I have enough money for the car insurance? Oh shit, day care just went up again. Jimmy grew 3 inches in the past 6 months and we have to buy all new clothes for him again.

Old people sit around in the morning reading/watching the news and screaming about how the idiots in DC are ruining America.

Most of the progressive younger folk in my conservative rural community will not join our local Democratic organization because they are turned off by both Democrats and Republicans. I’m not sure what they view as a functional model for governance and deciding who governs.

@James:

True. But it is also true that especially in the aggregate (individuals can be outliers) that we all grow up with a similar story and understanding of the world–and I think that matters in the main.

And there is, as you note, the penchant for humans to always want to try the same solutions because that is what they know.

@OzarkHillbilly:

But when one party nominates a guy in his late 70s and the other party nominates a guy in his late 70s, more youth turnout won’t help much.

Also: when the entire system is biased towards incumbents and name recognition, it should be no surprise that we get old politicians.

(It also doesn’t help that one needs a lot of money to run for office, something the young are not known for having).

Also, I would note that the candidate whom the Youngs really liked in 2016 was Bernie Sanders, not exactly a spring chicken.

@Steven L. Taylor:

The days of the so-called political machines and higher involvement of the so-called political elites addressed this problem to some degree. On the other hand, those days denied opportunity to many who have since been able to break through and attain office. Whether the changes were worth the Madison Cawthornes, Lauren Boeberts, and Marjorie Taylor Greenes who broke through is another question entirely.

Of course, the main culprit could simply be entropy, too.

Personally, I think what’s going on is that there just isn’t that many GenXers. They are part of a pop growth trough, not a bulge. There aren’t many voters; there aren’t many candidates.

@Steven L. Taylor: I think this is just another outgrowth of the popular vote primary selection process. There are no party officials who can tell a candidate their time is passed. I’ll beat my drum one more time: Bernie Sanders most consequential act in his entire political history has been his spiteful elimination of the superdelegates,a new that is a negative legacy, not a positive one.

Your points are well taken, however changing the guard does not necessariy mean that things are going to get better.

It looks like the Nuevo Wavo of Republican ‘leadership’ includes Matt Gaetz (40), Josh Hawley (42), Elise Stefanik (37), Kristi Noem (50), Ted Cruz (51). All of whom support the Big Lie and Insurrection of January 16th.

Very lovely.

@Michael Cain:

You say that like it wasn’t a bad thing.

After instituting order to the empire and establishing a tetrarchy, Diocletian took it one step further a few years later by retiring from his post as emperor, and insisting his co-emperor, Maximinian, do likewise. This was in so the younger junior emperors would take over, and in turn appoint two younger junior emperors.

As usual for the Romans, it ended up in a civil war, with one man, Constantine, rising to the top and ruling uncontested.

Good try, though.

@MarkedMan:

This is one of the things I am alluding to here, yes.

I take your point as a theoretical matter, but I would note the superdelegates, despite their theoretical significance, have never really mattered and, moreover, were unlikely to ever matter save in the unlikely context of a truly divided party.

Also: the issue of primaries is about more than just the presidential selection process, but is relevant all the way down to local office in terms of how the parties are formed and function.

Oh FFS. I’d say this is what I’d expect from AEI and Levin, except it’s exactly what I’d expect from David Brooks. A load of pop sociology deliberately obfuscating a reality Brooks/Levin prefer to avoid. And the lack of evidence or example throughout is striking. Oh deary, dear, our boomer leaders aren’t giving up power voluntarily. Unlike previous generations such as, well who actually? Do you have to go with @Kathy: back to ancient Rome?

I was born in 1946. And life did get better every year, not only for me and my family, but for the country. And that persisted into the 80s. And for France, Germany, Japan and most everybody else, who didn’t emerge from WWII un-bombed and as the most powerful nation.

So what did happen? Piketty says it was that the destruction of capital in WWII interrupted the concentration of capital in the hands of a few, which has resumed big time. Hacker and Pierson say it’s because corporate money started entering politics in a big way in the 70s. I’ll simplify, we started electing more Republicans. My personal perception that things were getting better survived Vietnam, but not the Reagan recession. Backed up by the Bush recession, the second Bush recession, and the Trump recession.

What stories? Again, examples? And why did this change? Maybe, just maybe, distrust of leaders has something to do with the GOPs and FOX’s decades long campaign against our “elites”? Their constant character assassination against Clinton, Obama, another Clinton, and now Biden? Maybe protests no longer work because GOPs allow nothing to change? Maybe the eroded value of college degrees and the need for two incomes reflects decades of voodoo economics?

James says,

OK, taxing the rich and investing in infrastructure go back to a (lost) bygone era. But Medicare for All? An assault weapons ban? A carbon tax? Filibustering everything? Police reform? Originalism? Universal Basic Income? Computer Aided Gerrymandering?

. No spit. Like Brooks, Levin throws a whole load of evidence free twaddle because he desperately wants to blame something, anything, other than Republicans.

@gVOR08:

My own crude approach is geographic, not generational. Nixon’s Southern strategy. In response, the loss of the “Rockefeller Republicans” in the Northeast, said loss expanding all along the BosWash urban corridor. The decline of the Midwest industrial unions, the rise of environmentalism as a force in the West. Benefiting the Republicans generally, as they picked up a bunch of smaller, more rural states from those changes.

What OzarkHillbilly and gVOR08 said. A load of evidence free twaddle indeed. For some reason I don’t see myself (born in 1946) in this gross generalization. More importantly, where do I go to get paid to write this pop sociology?

My point was only that there is precious little incentive to pander to the youth when they barely vote.

Hence, my statement of why I think the problem is systemic. What is the primary requisite for a leadership position in Congress? The ability to raise money, not just for themselves but for other party members and the party itself. The coin of the realm is, well, coinage.

We were handed a solution to this problem on a golden platter, but then all the libs were like “get vaccinated! wear masks! don’t eat horse paste!”

The advantages of incumbency are too great, and people tend not to think that anyone else can do their job.

The only society, real or fictional, that managed generational change was in Logan’s Run.

Also, let’s look at the prominent Gen X politicians… the only ones that are well known are complete right wing lunatics. I think Biden and the rest have to hang on for a few more years until the Millennials are ready.

(And then Gen Z should just take over through force if needed — they seem better)

It is interesting to note almost 100 years ago. Warren Harding was 57 when he died in office from cardiac arrest. Calvin Coolidge took office at age 50 who after leaving office pasted away at age 60. It isn’t just that the boomers are such a large age cohort it is that they are expected to be influncial well into their 80s. Rather than a 20 year reign of influence those born in the 1940s will have a likely 40 year period from the early 1990s to the end of the 2020s.

“A society grows great when old men plant trees in whose shade they shall never sit.” — Greek Proverb

As someone super interested in housing policy (I live in California) I realize the difference is less partisan politics and more “don’t mess with what I already have built”. Generational differences are going to happen no matter the partisan views. Interest in issues like child care, college costs, student loan debt, social security are going to vary greatly due your age.