What’s a Republic?

What meanings might the Founders have had? How should we understand the term?

Maybe a way to approach the “a republic, not a democracy” issue to stop talking about democracy for the moment, and shift to defining a republic. While I have done so in passing on multiple occasions I don’t think I have ever dedicated a full post to it.

Part of the fundamental problem of the formulation, “a republic, not a democracy” as deployed in American discourse is the assumption that the term “republic” or “constitutional republic” has a very specific meaning that is uniquely American and detached from the notion of democracy. Those who deploy the term appear to think that it somehow reflects a unique, and near-perfect, American polity than transcends other governmental types.

In truth, I think most people who use the term are really conflating federalism and its influences on institutional design (such as the Senate and the Electoral College) with the term “republic.” I think, too, the vast majority of people who use the phrase have almost no operative knowledge of governments outside the US, at least not in any detail.

Even more broadly, as an interaction in a previous post’s comment section demonstrates, the word has a colloquial connotation that may not really take into account its actual meaning.

An irony is that in the minds of most people, I would suspect that “republic” and “democracy” are largely equivalent terms (despite the stridency of the phrase that inspires this whole discussion).

The oldest usage of significance of which I am aware (and I would not suggest that I have ever fully studied the origins of the term in a systematic way) would be by Plato in his work, The Republic.

In that work, Socrates examines what constitutes justice and, by extension, a just regime. He discusses, as I have noted in other posts, the tension between governing in the private interest of the ruler versus governing in the public interest of the ruled. In simple terms, the republic is governing in the res publica or the common interest.

In The Republic, Plato outlines five regime types, in order from best to worst, with each a degeneration of the one prior.

- Aristocracy: rule by the best, i.e., the rational (selectively bred philosopher class)

- Timocracy: rule by the spirited (the warrior class)

- Oligarchy: rule by the wealthy

- Democracy: rule by the poor

- Tyranny: rule by a despot

It is extremely important to understand that these terms are linked to very specific meanings that do not fully reflect modern usage. The entire discussion is one that revolves around the three parts of the soul: the rational, the spirited/passionate, and the appetite. It makes assumptions about how some humans are dominated by different parts of the soul, and that that dictates their place in society.

The best regime in this typology was the one in which the rulers were those whose souls were dominated by the rational, i.e., philosophers (lovers of truth). The philosopher-kings were identified young and trained up to govern and bred by matching the rationally dominated citizens to each other to produce rational children. It was not to be a set of families, but an ever-rotating task of identification, breeding, and training.

When this system failed, the wrong people might make it into the governing class, those dominated not by reason, but by passion. This would lead to a lot of war to seek further glory. This cycle would lead to more degeneration as appetite crept in.

As such, when the spirited rulers started to be outnumbered by those with appetites for riches (oligarchs) the regime would degenerate from timocracy to oligarchy. Then, the jealousy of the poor masses would lead to the tearing down of the wealthy, and hence democracy (as they hungered for the material wealth of the oligarchs). The chaos of democracy would lead to the need for a despot to enforce order.

Basically: a focus in the rational would be replcaed by passion, then by varying appetites, before birthing a tyranny.

When Americans of the founding era decry “democracy” they are decrying mob rule by the poor as described by Plato (as well as by Aristotle and the Roman Polybius, who borrowed heavily from Aristotle).

But, I would note, Plato’s republic, a regime governed by a philosopher-king in the public interest, is by no means anything like what contemporary Americans think of when they hear the term “republic.” Nor does it bear any resemblance to modern constitutionalism (as defined by the late 18th-century onward).

Indeed, Plato’s republic is clearly authoritarian. It places power in the hands of the few. Its purpose is bringing a just regime that would allow for human flourishing and the good life, but through selective breeding, coercion, and the propagation of an official story to convince everyone to participate. It has a rigid class structure that is enforced by sometimes taking the children of one class and moving them into another. Indeed, the children of the upper class are raised in common so that no one knows whose child is theirs. And the ruling class is not allowed to accumulate wealth.

The Greeks and Romans influenced the founders to see “democracy” as either direct democracy (as the Athenians described it) or as mob rule by the poor (and both Plato and Aristotle described it). Neither has much to do with what developed as democratic governance in the 18th and 19th centuries.

The part that the Founders appear to have taken away from Plato regarding a “republic” was the notion of governing in the common good. They also took away some of the elitism wherein the wealthy and educated had a duty to govern, and should volunteer to do so.

I would note that trying to make one-to-one connections between the way the ancients used these terms and the way they are used now is problematic.

It is also worth noting that the US founding generation were living at a time of crossroads between older ways of thinking and new ways, especially about politics.

A more direct place the Founders would have understood the term “republic” would have been within the realm of a regime without a king or hereditary nobility.

This was the meaning in the Roman Republic, which began after the Romans did away with their monarchy and peristed until the time it became an Empire with an Emperor.

Note, for example, that after the French Revolution, the French went through a series of republics (it is currently in the Fifth Republic, which started with the 1958 constitution).

Both the United States of America and France adopted a lot of Roman symbology after their respective revolutions in the 1700s as a call back to what was seen as the last great republic. After all, the Americans had managed unilateral independence from their king, and the French beheaded theirs.

Keep in mind that almost all governments at the time were based on some sort of hereditary rule and so the distinction were pretty dramatic (hence, Franklin’s famous quip about “a republic, if you can keep it”–as the threat of being takne over by one of the monarchies of Europe was a real one in 1789).

Hence, in Article IV, Section 4 of the Constitution, we see the following: “The United States shall guarantee to every State in this Union a Republican Form of Government”–this is a guarantee of no monarchy and no aristocracy to go along with Article I, Section 9:

No Title of Nobility shall be granted by the United States: And no Person holding any Office of Profit or Trust under them, shall, without the Consent of the Congress, accept of any present, Emolument, Office, or Title, of any kind whatever, from any King, Prince, or foreign State.

Indeed, part of the reason the president has to be a “natural born citizen” is to stop the possibility of someone of European aristocratic descent migrating to the US and then seeking the presidency.

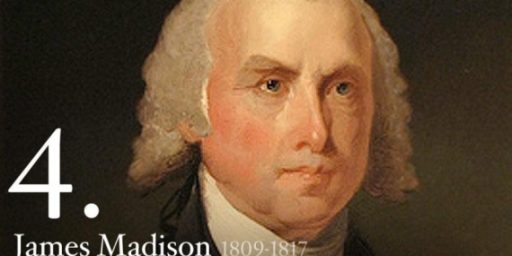

I would note that the main way the system was “republican” was that all officies in government had some connection to popular elections, even the ones that were appointed. The Senate, for example, were appointed by state legislatures which were elected by the people of the states. (See Madison and Federalist 39 for example).

Some other passing examples. Why is the independent country the Republic of Ireland called that? Upon gaining its independence from the United Kingdom, it was able to rule itself without a monarchy. The Irish separatist group, the IRA, stands for Irish Republican Army. They called themselves that because that wanted a republic, i.e., a government without a king.

Likewise, when the Spanish colonies of Latin America fought for independence in the early 1800s, they all became republics as soon as they stopped being under Spanish rule. I would note that while some tried to apply some of the trappings of democratic governance, they really were mostly oligarchies as best, but still republics. Some became pretty significantly authoritarian, but were still republics.

Brazil, for those scoring at home, did not become a republic at independence but eventually ousted its monarchy in 1889.

It is worth noting that the United Kingdom is a monarchy, as its head of state is a hereditary ruler. However, it is also a democracy, since its government is elected by the people. Other examples include Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Spain. For that matter, Queen Elizabeth II is also the Queen of Australia, Canada, and New Zealand.

One last thought, a republic need not been an especially liberal regime. I know that those of us who grew up in the Cold War likely heard people mock the fact that the USSR stood for the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics or that the PRC is the People’s Republic of China. Surely that was just propaganda aimed at making those regimes sound better than they were, yes?

In simple terms, let’s note the following: the USSR was founded as the result of a revolution that overthrew a hereditary ruler. The PRC was established as the result of a revolution that overthrew a hereditary ruler. Further, the Islamic Republic of Iran overthrew a hereditary monarch to establish a theocratic regime. Note that all held firm to ideologies that claim to derive their power from the people. Indeed, since all three are examples of popular revolutions, they had an objective reason to make that claim at their origins.

In terms of the basic definition of a republic as a form of government that does not rely on a hereditary nobility to govern, but derives its power from the people, calling these countries republics is appropriate.

Now, can we criticize these regimes for how they treat their own people? Yes. Can we call into question the degree to which the governments establised by their respective revolutions still take into account the consent of the governed? Yes.

But, of course, even if their origins are republican, they are not democracies.

Indeed, part of my political sciences doesn’t talk about “republics” all that much is because “republic” is not a regime type. It is a descriptor that tells us whether a country has hereditary rulers or not. But it tells us nothing about how that country is governed. It tells us nothing about the power of those hereditary rulers nor about how much input the people actually have.

Rather, political science focuses on whether regimes are democratic or non-democratic (i.e., authoritarian). Now there are a number of institutional variations in democracies (e.g., Is the head of state an elected president, an appointed president, or a monarch? How is the head of government chosen?) and of authoritarian regimes (e.g., single-party rule, personalistic dictator, military regime, theocracy, etc.).

Indeed, of the various reasons “a republic, not a democracy” drives political scientists crazy, is because the dichotomy makes no sense. First, this is comparing an element of a regime type (republicanism) with a regime type (democracy). Second, they are not mutually exclusive categories.

But, to be clear, the main objection is that the formulation is ultimately nonsensical. (And if people want to defend things like the Electoral College, then do so, and cease this hand-waving).

Aside from the laudable goal (I think at least) of linguistic clarity, the real issue should be what is that if calling America a “republic, and not a democracy” is an excuse for minority rule, then that’s a problem (and is a rejection of democracy, broadly defined)?

From both a theoretical point-of-view and a normative one (i.e., a values based assessment), I find that problematic.

And to be clear, as some seem to be missing this point: minority rule means a governmental system wherein the numeric minority has more power than the majority. The fact that Donald Trump is president, and able to appoint members to the Supreme Court is an example of minority rule because he came to office with less support than his competitor. Stating that it is that way because the US is “a republic, not a democracy” doesn’t change that fact, nor does it provide an argument in defense.

The fact that Senate seats are allocated in a way that a minority of citizens control a majority of votes is an example of minority rule.

The fact it is possible for the national vote for the House to go to one party, but for the majority of seats to go to the other, is an example of minority rule.

The fact that Wisconsin is so gerrymandered that the state legislature is dominated by the party that got fewer votes is an example of minority rule.

In all of these cases, the power to make binding governmental decisions is made by individuals or groups that have less support than the individual or group out of power. That is problematic, especially since it seems to be a growing phenomenon.

Stating that all of that is ok, because “we have a republic, not a democracy” is a dodge at best.

And, to conclude: allowing for minority rights (free speech, freedom to worship, etc) is not minority rule. It is an acknowledgment that some rights transcend majority preferences. It is both separate from the question of who governs at a specific moment in time as well as being an essential part of democratic governance.

Very interesting and informative.

Especially for someone like me with a STEM (engineering) education – not much liberal arts type stuff.

As I read this, I kept thinking, ow, here’s a point that I can flush out in the comments and darn, if you didn’t address that in the next paragraph.

Nice work.

Many thanks for this particular OP. I’d add (history major) that the Founders had a fairly recent example in mind in the English Civil Wars of 1640s and on to the Glorious Revolution of (trusting memory) 1688 which led to the supremacy of Parliament within a monarchy in which they had chosen their own king (William of Orange — and I was right! 1688.)

There were quite a lot of ‘royal’ families to be found in Europe and one possible end of the American revolution of 1776 was for the Founders to pick their own monarch as the English had done. ‘Our’ revolution followed only by some 50 yrs the English ‘Act of Settlement’ in which a different dynasty (the Hanovers) was selected to keep England protestant. So Parliament had actually chosen two dynastic royals when the Constitutional Convention met in Philadelphia.

It’s been a very very long time since I studied all this, but I am pretty sure that not a single ‘Founding Father’ advocated for an absolute democracy or described what such a polity would look like. A democracy through representatives was always the obvious choice if a monarchy was rejected. And as I recall that is what a ‘republic’ designates: A government of representatives of the people.

While I don’t disagree with your larger point, I don’t think this is entirely right.

A res publica is ot so much the common interest as a “a public thing” / “a thing that is public,” as opposed to a res privata.

During the Roman Republic, the government itself was a res publica, because every Roman citizen* had a say in it – as opposed to government as a res privata, where only the monarch ruled.

* It should be noted, of course, that most Romans were not citizens and that wealthy citizens could always outvote the much, much more numerous poor citizens. (Obviously, the non-citizens don’t even register here.)

While both republic and monarchist forms of government were expected to rule in the common interest, Roman republicans believed, however, that making the government a res publica was an effective insurance against tyranny – both against the tyranny of the autocrat and the tyranny of the masses – and thus was the only form of government that created the necessary conditions for rule in the common interest.

This is also, ultimately, where the notion comes from that republics protect the minority against the tyranny of the majority.

However, as I pointed out yesterday, republics – whether it is the Roman Republic, the medieval Italian city states, the Dutch Republic, or the early American republic – were never intended to protect oppressed minorities (even though they generally did a better job than contemporary monarchies). They were meant and designed to protect the minority currently in charge.

Based on what I wrote above, this makes sense as both the Senate and Electoral College were designed to protect landholding and wealthy minorities against the (expected) tyranny of the poor and landless masses.

As we are increasingly witnessing, federalism is doing more and more what was originally intended to do: to protect landowners against the majority.

Thus, it is not a coincidence that federalism and republicanism are being conflated in some arguments. But those who do so, are implicitly arguing for 18th-century power relations.

However, it goes without saying that 18th-century notions of good government are incompatible with democracy in the modern sense of the word.

@drj:

I should add that it has been a GOP talking point for (at least) decades now that masses of lazy and shiftless Democratic voters will vote for more social security so that they can unjustly profit off the hard work of Real (landowning) Americans(tm).

Certain reactionary ideas have quite a long history…

@JohnMcC:

Exactly.

@drj:

All fair and more nuanced and detailed conversation could be had.

I was thinking about Plato’s usage, not the Roman Republic’s, however. Still, a deeper parsing of the exact meaning is utterly fair.

Indeed.

And you would think it would go without saying, and yet it clearly needs to be said to some folks.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Plato used the word “politeia.” While “politeia” is generally translated in English as “republic,” this translation is both inaccurate and anachronistic. I’m sure that the fact that Plato’s “Politeia” is usually called “The Republic” in English is mostly at fault here.

A better translation of “politeia” would be “political system.” A “republic” is a particular form of political system that Plato doesn’t recognize as such. “Republic” has no place among his five regime types.

Not much relevant for the general point, but I think Mexico (and by inclusion almost all Central America) was also a monarchy in the first years after independence.

@drj: As a point of order it is not true most Romans were not citizens, unless you are including slaves, but that’s rather distortive (or if you are counting conquered peoples, but they were not Roman…). Rome’s rather catholic and expansive attitude to citizenship was a key distinguishing feature in comparison with the rest of the classical world.

More of substance, it seems to me that the reaction in the USA at present is not Wealthy against Poor Masses but very much ethno-nationalist, as the divide does not follow well Wealthy / Non Wealthy, but does track well Urban – Rural and rural and semi-rural tracks rather well as well White. Even the type of wealth on the side of Trump is distinguishable from that which is not.

You know, I’ve heard about Plato and the “philosopher kings” for a long time, but somehow, reading your description, it occurred to me that it could be understood as “bureaucrats”. Particularly the Confucian bureaucrats that de facto ran China for centuries. That worked, but still had issues. Or am I off base?

@Lounsbury:

While we could quarrel about definitions (and I certainly could have been a bit more precise), it is simply a fact that at no point a majority of those under Roman rule could participate in political life.

* While Roman women were considered citizens, they could not vote or stand for office.

* Slaves were considered property

* Freedmen were often not given citizenship

* Provincials were only given citizenship in 212 CE, when the Republic was dead for over two centuries.

So I’m pretty sure my point stands.

The GOP represents money first and foremost. Ethno-nationalism is just a means to get the rubes on board.

Same thing with Brexit. I’m pretty sure your Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson and Jacob Rees-Mogg are not particularly bothered by Polish plumbers, or Romanian ophthalmologists getting hired by the NHS.

It has been a persistent goal of the GOP to make “democracy” and “rule by the poor” synonymous in the US, by the simple expedient of ensuring that most people who can vote are poor. As the “rotten boroughs” of English history showed us, in some ways democracy can be a better mechanism for oligarchy than direct oligarchy is.

@drj: Well very simply the assertion was incorrect, Rome polis born free persons were broadly citizens, in stark contrast with the practice of other classical entities. By normal citizenship boundaries the majority of Romans were citizens. Sure if you throw in non-Romans they are not citizens, but that’s rather like counting Canadians with Americans for some observation on Americans. Freed slaves rather generally gained citizenship, Italians, etc. Counting imperial Rome conquered provinces is purely distortive. Although the Roman lesson of extensive granting of citizenship to allies rather carries a rather more useful lesson that contrasts it with the near universal restrictive practice of its classical peers. That lesson being the rather liberal Roman approach as compared to its peers was by all accounts a key to its longevity and success as a state with broad buy-in from the ruled populations. Rather more useful an insight, particularly for an immigration based America.

Yes, the position of the Ideological Left, resolving down to your pet pre-sets.

It is rather clear that ethno-nationalism is something rather real inside that party now, not merely “just a means” – that is in fact the problem, while it likely well began as that, it no longer is, and both Left and Right are making quite a fundamental error in thinking it is.

Of course it is a further error to see The Wealthy as one thing, the type of wealth backing the Republicans at present is not the same type as joining either Never Trump or centrist Democrats. Grossly simplistic thinking to lump it together.

Neither are mine however this illlustrates the mistake. The economic interests of the urban southern wealthy classes are rather better served by liberal and open trade – thus the Thatcher backing of joining the economic free trade zone. The Reaction to such free trade comes from a different class of wealth than is usually dominant, and while opportunistically ridden by a Boris, he’s merely a professional opportunist. The Brexit reaction including amongst Conservatives is not something that resolves to Interests of the Wealthy as the most wealthy and the centre of English wealth is London interests who were and are solidly anti. Rather 2nd rate declining urban, northern Rural (wealthy or not – although with general economic decline those with centres of economic wealth there look generally at long-term decline) – a rather cultural reaction.

@JohnMcC: I think indeed these examples are among the most instructive, as much or more than the Classical which 18th century elite loved to dress up their contemporary concerns in. Worrying about a replay of Orange and Hannover invitations would indeed have been structurally central – and if one looks to the initial history of say Mexico and Brazil (or of Europe of course), not at all misplaced at the time (although looking at it now perhaps not well-addressed).

@Lounsbury:

Yes. The number of true believers inside the party is steadily increasing. But if you look at actual legislation, it is quite clear that monied interests are still in the driver’s seat.

In the US, despite all the rhetoric, we haven’t seen serious enforcement action against employers of illegal immigrants, for instance.

The Trump tax cuts benefited the very wealthy rather than white males without college degrees.

Etc., etc.

While it is likely to eventually happen if current trends continue, we are definitely not yet at the point that the majority of wealth has abandoned either the GOP or the Conservative and Unionist Party.

A working definition of Republic taking into account the HUGE precedents of Rome and the United States, is as follows: A democratic form of government where the powers of government are divided, limited, and checked in various ways, and derives legitimacy from the consent of the governed through suffrage.

Democracy is taken by the “a republic not a democracy” people to mean unlimited majority rule. Ergo their claim that 51% of the population could enslave the other 49%. I’ve no idea what nation or polity has ever undertaken this form of rule.

Lastly, while manu nations have incorporated the word “republic” in their official names, not one has ever, to my knowledge, used the word “democracy.” At most, the word used is “democratic,” but along with the word “republic.” Like the former East Germany was officially the German Democratic Republic.

@drj:

‘Monied interests’ in areas economic, however the Republican party is spending more and more effort on cultural legislation largely contrary to the broad interest of modern firms but rather responsive to a sub-set of traditional.

The ‘evolution’ on Free Trade under Trump also shows such even in the economic sphere.

However serious efforts at cutting off supply, against the interest of certain kinds of employers – those essentially urban, essentially modern, whose interest is rather more to a formalized immigration framework and not towards off-the-books labour. Contra the rural to semi-rural traditional industrial segements which have a cultural alignment in reaction to globalisation.

Simplistically resolving down to monied interests entirely misses a serious split in interest that is as much cultural as it is economic.

Of course the barking Left does love to resolve all political down to capital.

And? This is a red herring, as you will not find supra any statement about majority or minority of wealth (as it is first so vague as to be unfalsifiable and secondly quite irrelevant to the question of the driving force of ethno-nationalism in that particular Party for its agenda).

@Kathy:

Rome was not a democracy so really very peculiar comment, and there are plentiful examples of non-democratic Republics. The Democracy observation is linguistically naive (democratic being the natural adjectival reference to a democracy in such a name form)

@Kathy:

Indeed–it has never existed, and hence why I call it the strawiest of straw men.

I suppose my a key annoyance with “a republic, not a democracy” is that it ultimately means, “we have a magic thing, not that other thing that has never existed.” As someone who has studied politics for a living for decades, it is just thoroughly maddening.

@Lounsbury:

Rome was a democracy by their own reckoning, as much as several Greek city-states were. We wouldn’t call them that now, not when they excluded women from the vote, and held on to chattel slavery. They also excluded many, but not all, non-Roman Italian men from voting, which led to the Social Wars late int eh Republic period

So let me amend my definition to describe a “modern republic”.

Rome did have divided and checked government powers. The highest magistracy, the consulship, was limited to a one-year term, and one could not run for that office again for ten years (all that crashed later on, especially with Marius).

IMO, the big problem today in America is that the checks and balances written into the Constitution have been superseded by partisan checks and balances. Pretty much:

Our party will do everything it wants that it can get way with, so long as we control the presidency and the Congress. When we don’t control the two branches, we’ll simply block the other party as much as we can get away with, providing the minimum governance needed to keep the country running.

That’s rather unsustainable.

@Steven L. Taylor:

About the closest thing I can think of is Ostracism in Athens. And I think that was limited to one person expelled from the city for ten years.

Now, come to think of it, we could scare up enough votes to ostracize Trump. Surely Putin would be glad to have him for a decade.

@Kathy:

I think the classical example used by the premodern anti-democratic thinkers was the execution of Socrates (the teacher of Xenophon and Plato, who for his turn was the teacher of Aristotle).

But the French Revolution, in the 1972-94 period, was probably the best example, with the Parliament (the “Convention”) regularly voting to expel (and execute…) the representatives of some minority faction.

@Kathy:

My comment was on their own basis, not ahistorical analysis re women or slavery as it would be archly ahistorical. I suppose I can allow the early Republic as a democracy on that basis and so withdraw that objection.

@Miguel Madeira:

hmm I don’t quite remember this….;^)

@Miguel Madeira:

You’d think Socrates was the only man ever executed in Athens 😉

As to the French Revolution, it was more of a rolling civil war amid uniting to fight invaders and regions of die hard royalists. With so many restrictions on suffrage, that not even all male citizens could vote.

About ostracism, there is an anecdote about an ostracized Athenian statesman called Aristides. During the vote for ostracism, a citizen asked him to write his vote for him, most citizens being illiterate. Aristides agreed, and the man named Aristides as the party to be ostracized.

Dutifully, Aristides wrote his own name down, and then asked the man “Has Aristides wronged you?”

“No,” the man replied. “I’m must angry that everyone calls him ‘the just’.”