Justices Again Appear To Be Divided In Second Partisan Gerrymandering Case

The Supreme Court heard oral argument in the second partisan gerrymandering case of the term, and once again they appear to be divided.

The Supreme Court heard oral argument today in the second of two cases it has accepted this term dealing with the issue of Congressional redistricting and the extent to which district boundaries can be drawn based on partisanship:

WASHINGTON — For the second time this term, the Supreme Court heard arguments on Wednesday about whether voting maps can be so distorted by politics that they violate the Constitution. But if the first arguments heartened opponents of extreme partisan gerrymandering, this hearing only served to confuse them.

The earlier case, from Wisconsin, was argued in October, and several justices seemed intrigued by the idea that the Constitution may place limits on extreme partisan gerrymandering, where the party in power draws voting districts to give itself an outsized advantage in future elections. A decision is expected by June.

The Supreme Court has never struck down a voting district as an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander. A ruling allowing such challenges could revolutionize American politics.

The court’s surprise announcement in December that it would hear a second partisan gerrymandering case, Benisek v. Lamone, No. 17-333, led to much speculation about what the move meant for the challengers in the Wisconsin case, Gill v. Whitford, No. 16-1161. But Wednesday’s argument did almost nothing to clear up the mystery of why the justices decided to hear a second case.

Several justices said the new case, from Maryland, was plagued by procedural and practical problems.

Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Sonia Sotomayor said there was little reason for the court to rule now because its decision would come too late to affect the 2018 elections. Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. said the challengers had waited too long to file suit.

If there was a hint about where the court was headed in the Wisconsin case, it came from Justice Stephen G. Breyer, who suggested that the court schedule a new round of arguments in both cases, along with one from North Carolina, in the term that will start in October.

Justice Breyer, who seems ready to allow constitutional challenges based on partisan gerrymandering, probably would not have made the suggestion had his views prevailed when the justices took their preliminary vote in the Wisconsin case in October.

The Maryland case is a challenge to a single congressional district, while the older one challenged a statewide map for the Wisconsin State Assembly. The new case was brought by Republican voters, while the older one was brought by Democrats. And the new case relies solely on the First Amendment, while the older one was pursued largely on equal protection principles.

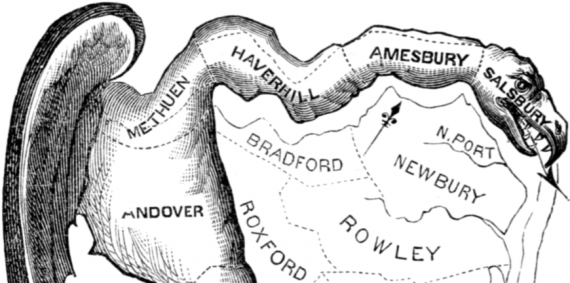

Michael B. Kimberly, a lawyer for the plaintiffs in the Maryland case, argued that Democratic state lawmakers there had redrawn a district in northwestern Maryland to retaliate against citizens who supported its longtime incumbent, Representative Roscoe G. Bartlett, a Republican. That retaliation, he said, violated the First Amendment by diluting their voting power in a district that had been controlled by Republicans.

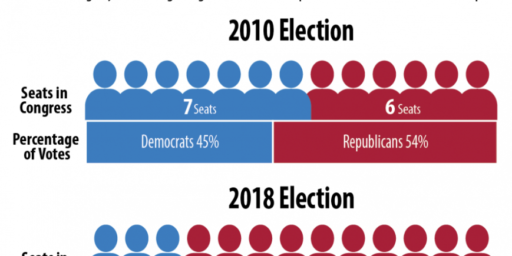

Mr. Bartlett had won his 2010 race by a margin of 28 percentage points. In 2012, he lost to Representative John Delaney, a Democrat, by a 21-point margin.

Several justices said the evidence of extreme partisan gerrymandering was strong.

Justice Elena Kagan said that in some cases it might be hard to tell when politics played too large a role, but she said that was not a problem here. “However much you think it too much,” she said, “this case is too much.”

Chief Justice Roberts criticized the challenged district’s odd shape. “It doesn’t seem to have any internal logic,” he said.

Steven M. Sullivan, Maryland’s solicitor general, said there had been a close race in 2014 and that the district’s political future was uncertain. This, he said, was hardly evidence of unconstitutional partisan gerrymandering.

When the Wisconsin case was argued in the fall, a majority of the court seemed at least open to the possibility that some kinds of partisan gerrymandering are unconstitutional. Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, who probably holds the decisive vote in both cases, asked several questions in October about the First Amendment theory relied on by the challengers in the new case.

In the past, some justices have said the court should stay out of such political disputes. Others have said partisan gerrymanders may violate the Constitution.

Justice Kennedy has taken a middle position, leaving the door to such challenges open a crack, though he has never voted to sustain one.”

Amy Howe at SCOTUSBlog summarizes the argument further, and as she notes the Justices appear to remain as uncertain on the issue of when partisan gerrymandering becomes a Constitutional issue as they have been in the past:

The issue of partisan gerrymandering and what (if anything) to do about it has bedeviled the justices for years – as today’s oral argument once again demonstrated. In 2004, a deeply divided Supreme Court declined to step into a dispute over Pennsylvania’s redistricting plan. Justice Anthony Kennedy provided the pivotal vote in the case: He agreed that the Supreme Court should not intervene, while at the same time leaving the door open for courts to review future partisan-gerrymandering cases if a workable standard could be found. And last October, the justices heard oral argument in a partisan-gerrymandering challenge to the statewide redistricting plan enacted by Wisconsin’s Republican-controlled legislature. Although there seemed to be a fairly broad agreement in the Wisconsin case that partisan gerrymandering is, as Justice Samuel Alito indicated, “distasteful,” there was no apparent consensus beyond that. Two months later, the justices announced that they would also review the Maryland case, known in the Supreme Court as Benisek v. Lamone.

If spectators had hoped that today’s oral argument might shed some light on how the justices had voted on the Wisconsin case, they were – unless the justices have excellent poker faces – largely disappointed. Instead, it seemed entirely possible that the justices were counting on the oral argument to give them new insight into a solution to the thorny problem of partisan gerrymandering. But before they even got that far, justices of all ideological stripes expressed doubt about whether they should rule on the partisan-gerrymandering question at all when the case came to them as a request for preliminary relief, rather than for a decision on the merits, and their ruling would come too late for any changes to the state’s congressional maps before the upcoming 2018 election.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the justice most likely to pay attention to procedural issues, kicked off the questioning. She asked attorney Michael Kimberly, who argued for the challengers in the case, how his clients would be irreparably harmed if preliminary relief were not granted when nothing would happen to the 6th district until 2020.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor chimed in, telling Kimberly that his clients had waited “an awful long time” to bring their lawsuit.

Chief Justice John Roberts then joined the fray, noting that several elections in the redrawn 6th district been held before Kimberly’s clients challenged the map. If the challengers were “willing to let go” of the earlier elections, he suggested to Kimberly, doesn’t that mean that they would not be irreparably harmed if the 2018 election went forward under the existing map?

When the justices did eventually turn to the question of partisan gerrymandering itself, the concern at the heart of the Wisconsin case resurfaced: How should courts evaluate claims of partisan gerrymandering? As Justice Samuel Alito stressed to Kimberly, the Supreme Court has recognized that redistricting is an inherently partisan process, and that a desire to give the party in power an advantage is not, standing alone, problematic.

Moreover, there was no obvious consensus among the justices on how courts should determine when politics has played too strong a role in redistricting. Sotomayor and Justice Elena Kagan clearly believed that, under any standard, the 6th district would fail because of the “strong evidence” that Maryland officials had indeed engaged in partisan gerrymandering. Kagan told Maryland solicitor general Steven Sullivan that even if the state is correct and the challengers have not “shown how much is too much” – that is, come up with a workable standard – “however much you think is too much, this case is too much.” Everyone was very upfront about what they were doing, Kagan observed: The 6th district went from being 47% Republican and 36% Democrat to exactly the opposite. How much more evidence of partisan intent do we need, Kagan asked?

Justice Stephen Breyer, however, was not ready to join Kagan in declaring the 6th district a partisan gerrymander, without more. That won’t solve the other cases, he emphasized. And going forward, he noted, courts won’t have such clear evidence of the officials’ intent, because mapmakers “aren’t stupid.” How, he asked, do we deal with the broader problem of partisan gerrymandering?

Breyer proposed a solution: The court should hold reargument not only in the Maryland and Wisconsin partisan-gerrymandering cases, but also in the North Carolina partisan-gerrymandering case that is currently on hold for the first two cases. He characterized the three cases as presenting “slight variations” on the same theme, in the sense that there is a constitutional violation – partisan gerrymandering – and the Supreme Court has been asked to provide a practical remedy that won’t result in the courts getting pulled into each and every redistricting dispute. Holding simultaneous reargument in all three cases, he suggested, would allow the justices to review all of the theories in the cases (not to mention the pros and cons of those theories) at once. Breyer’s colleagues on the bench, though, didn’t seem to share his enthusiasm for the idea of reargument.

The past year or so has been a fairly active one regarding legal challenges to redistricting decisions with what appear to be rather obvious partisan biases. The process began when the Justices agreed to hear the case arising out of Wisconsin near the end of its prior term. Oral argument in the Wisconsin case was held on the second day of the court’s current term and, at the time, it appeared that while the Justices did recognize the problem of extreme partisan gerrymandering, there was significant doubt on all sides about the extent to which the courts can or should come up with rules that legislatures can abide by when engaging in redistricting. The Justices also seemed to be mindful of the fact that whatever decision they could hand down could end up resulting in redistricting fights pushed into the Courts on a far more regular basis, a development that isn’t necessarily a positive one for either the Judiciary or the political process. Notwithstanding those concerns and the rather obvious split that the oral argument in the Wisconsin case revealed, the Court surprised many observers by accepting this case out of Maryland for oral argument back in the later part of 2017. At the time, many observers took this as a sign that the Justices remained divided on the Wisconsin case and took on the Maryland case in the hope that it would provide further insight into the questions presented in the Wisconsin case.

In the time since the Court accepted this Maryland case, there have been other legal developments on the political gerrymandering front that the Justices were no doubt aware of when they walked into the courtroom this morning to hear the case. In January, for example, a three-judge District Court panel in North Carolina ruled that the Congressional map in the Tarheel State violated the Constitution and that the state must redraw the map due to the fact that it unfairly benefits one political party. Just a few weeks later, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court made a similar ruling with respect to the Congressional Districts in the Keystone State, the major difference between this case and the other three, of course, is that the Pennsylvania ruling is based on the state Constitution rather than Federal law or the U.S. Constitution. Because of this, the Justices have so far declined to intervene in the Pennsylvania case, and the state Supreme Court moved forward with its threat to issue its own redistricting map when the Republican legislature and Democratic Governor failed to come to an agreement on a new map. The state will conduct the 2018 midterms based on that new map, and by all expectations Democrats appear likely to gain power in Pennsylvania’s Congressional delegation because of the new district lines.

As with the oral argument in the Wisconsin case, it’s hard to read where the Justices stood by the time the oral argument was over today. Based on the summaries, though, it seems apparent that they are likely in the same place they were in October. Because of this, the suggestion that Justice Breyer made is an intriguing one. As noted above, Breyer suggested that the Court could set both this case and the Wisconsin case over for re-argument and that it should accept the North Carolina case for argument and combine all three cases in a way that it would allow it to address all of the issues raised by this issue in a comprehensive opinion. While it didn’t appear that any of the other Justices were immediately inclined to go along with Breyer’s suggestion, it would not be an unprecedented move if the Court were to do this. Several times in the past, the Court has set complicated cases over for a second round of briefing and argument, and combined them with cases raising similar issues. If that were to happen in this case, of course, it would mean that argument would be heard during the term that begins in October of this year, with a decision not likely until some time well after the 2018 midterms. To the extent that the Justices are concerned about any ruling that could cause chaos for the upcoming midterms, this could be an ideal situation.

Whatever the outcome, as with the Wisconsin case, we’ll likely have to wait until June to see what the Court decides to do.

Here is the transcript of today’s oral argument:

Benisek Et Al v. Lamone Et Al Oral Argument by Doug Mataconis on Scribd