The Republican Advantage in the House

Any "fair" drawing of districts will yield a GOP advantage over time.

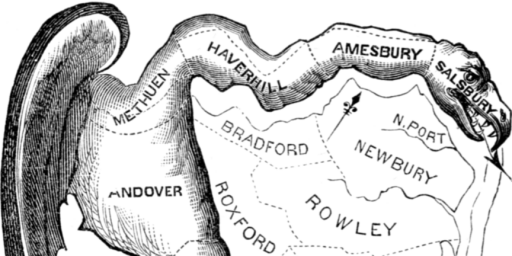

That Republicans have a natural advantage in the Senate, and therefore the Electoral College, has been the subject of many posts here and elsewhere over the years. Less remarked is the Republican advantage in the House of Representatives, which is generally presumed to be a result of gerrymandering. It turns out to be much more complicated.

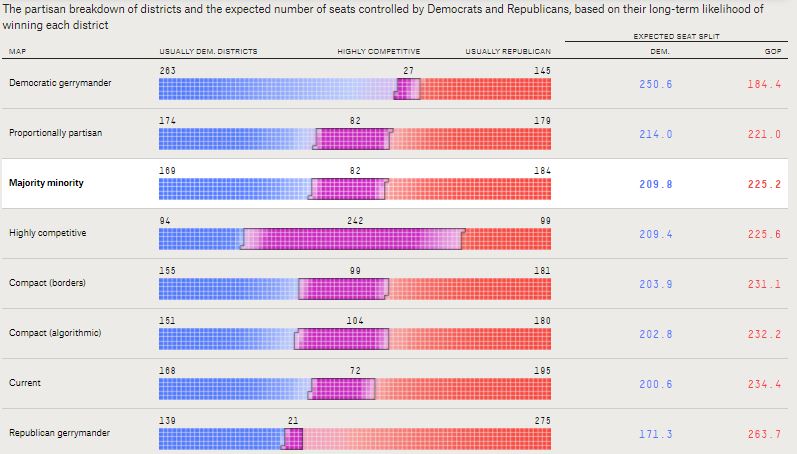

The gang at FiveThirtyEight have undertaken The Gerrymandering Project since January 2018. The simple premise: we can all agree that having politicians draw Congressional districts to maximize their party’s chances of winning is suboptimal but not on what precise alternative is best. So, they show us eight possible outcomes using eight prioritization models:

1. Current districts

These are the congressional districts currently in effect for the 2018 elections. The probabilities listed on this map do not reflect predictions for the 2018 election specifically, but instead are how often we’d expect each party to win the seat over the long term based on its Cook PVI across a variety of political conditions.

2. Republican gerrymander

This map seeks to maximize the number of usually Republican districts — those with a Cook PVI of R+5 or greater (which we’ve found corresponds to at least an 82 percent chance of a Republican victory). Where additional strongly Republican districts are not possible, this map seeks to maximize the number of competitive districts (Cook PVI between D+5 and R+5). Think of these maps as extreme Republican gerrymanders — a reference point for how far Congress could be pushed to the right.

3. Democratic gerrymander

This map seeks to maximize the number of strongly Democratic districts (Cook PVI of D+5 or greater). Where additional strongly Democratic districts are not possible, this map seeks to maximize the number of competitive districts (Cook PVI between D+5 and R+5). Think of these maps as extreme Democratic gerrymanders — a reference point for how far Congress could be pushed to the left.

4. Proportionally partisan

This map seeks to draw districts that favor each party in proportion to the overall political lean of each state. For example, if a state has 10 districts and Republicans won an average of 70 percent of its major-party votes in the last two presidential elections, we drew seven districts to favor Republicans and three to favor Democrats.

5. Highly competitive

This map seeks to maximize the number of highly competitive districts — those with a Cook PVI between D+5 and R+5. In terms of probabilities, that means both parties have at least an 18 percent chance of winning these seats.

6. Majority minority

This map seeks to maximize the number of districts where members of a single minority group make up a majority of the voting age population. Because of lower rates of citizenship among Latinos, the map strives to create 60 percent Hispanic/Latino districts where possible. Where additional majority-minority districts are not possible, the map seeks to maximize “coalition” districts where no racial group makes up a majority.

7. Compact (algorithm)

This map is based on Olson’s computer algorithm, which seeks to minimize the average distance between each constituent and his or her district’s geographic center. It is the only set of state maps (other than the current congressional boundaries) that we did not draw by hand. It is based on census blocks and is blind to race, party and higher-order jurisdictional boundaries like cities and counties. It makes no attempt to adhere to the Voting Rights Act.

8. Compact (borders)

This race-blind and party-blind map seeks to maximize compactness by using counties as building blocks when drawing districts. The map splits counties only as many times as necessary to create equally populous districts, and where possible, entire districts are kept whole within counties, metro areas and regions. When counties are split, the map seeks to minimize splits of county subdivisions, such as cities and townships. It makes no attempt to adhere to the Voting Rights Act.

Just reading the criteria and not knowing the results, my preferences would be Highly Competitive and Compact (borders); I can argue either way for which of those two to prefer. Given the intent of Congressional Districts is to represent communities, I probably lean slightly toward the latter but given the reality of how the modern party system operates, the former is more likely to produce good governance.

Regardless, here’s how they predict average elections would go with each set of maps:

What stands out here is that, absent Democratic cheating, Republicans come out ahead. That is, as Dave Schuler pus it, “the only districting methods that ends up with a number of Democratic representatives greater than or equal to the present number are the present one and the Democratic gerrymander.”

Which is odd, right? There are far more Democrats than Republicans nation-wide. But, as Dave correctly observes, “That result which may be counterintuitive to some is a consequence of something that is just as true at the state level as at the national level: we don’t vote at large.”

Indeed, seven states have no districts at all–just a single at large Representative.

As Harry Enten explained when the project launched, “Ending Gerrymandering Won’t Fix What Ails America.”

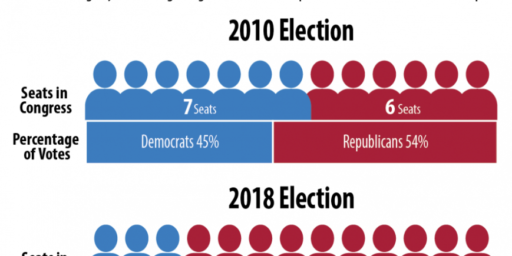

The states, counties and even neighborhoods from which districts are drawn are less competitive than they used to be because voters are sorting themselves. People are changing their political opinions to be more like their neighbors’, and people are moving to regions where their political viewpoint is more common. This “self-sorting” means more and more areas come, in essence, pre-gerrymandered — dominated by partisans. That makes it more difficult to draw competitive districts without an increased effort to do so.

You can see this pretty clearly if you look at the votes cast for House candidates aggregated to the state level (obviously, states can’t be gerrymandered). In 1996, the difference in the cumulative House vote for Republicans and the cumulative House vote for Democrats was 10 percentage points or less in 22 states. By 2016, there were only 16 states that close. You can see something similar if you look at how states voted in presidential elections, as well: The number of states whose vote share margin was within 10 points of the national margin dropped from 27 in 1996 to 16 in 2016.

It’s even clearer that voting is more homogenous by community than it used to be when you look at counties, whose boundaries also can’t be gerrymandered. If gerrymandering were the sole culprit behind the decline in competitive districts, the number of counties that are competitive in presidential elections should have barely shifted. Instead, there’s been massive movement.

In 1996, there were 1,111 counties (about 35 percent of the total)5 where the margin in the presidential vote was within 10 percentage points of the nationwide margin. By 2016, that number had plummeted to just 310 (about 10 percent).

Despite the fact that Democrats won the House in 2018 and kept it in 2020, the decks are stacked against them. Yes, Republican gerrymandering contributed to that. So did Republican voter suppression tactics. But, mostly, it’s a function of the system we used to select them: there are too few representatives and they’re elected in single-member districts.

Steven Taylor has written a lot about the problems with our electoral system, going back at least a decade. See, for example, “There is Something Fundamentally Wrong with Congress” (December 2011), “Are we Finally Starting to Talk about Electoral Reform?” (November 2018), “Reforms: the Possible, the Improbable, and the Unpossible” (August 2020), and “Our Unrepresentative Government (Yet Again)” (February 2021). But, aside from political scientists and election wonks, it’s not a subject of much debate.

Increasing the size of the House, so favored by OTB alumnus Rob Prather that he’s incorporated it in his Twitter name, is the simplest and most obvious of the fixes. It has been fixed in law at 435 since 1929, when the population was a mere 121.8 million; it’s 330.1 million now. But I’ve seen essentially no clamor for that. I fear that multi-member districts and other fixes would be seen as too exotic and “foreign” to get much of a hearing.

I, for one, welcome our new 1,100 member House 😉

Gonna need a bigger Capital though.

As I have repeatedly noted: one of the most, if not the most, fundamental flaw of our electoral system for electing legislatures is the usage of single-seat districts.

It privileges the geographic distribution of where people live over the actual distribution of political interests in the population.

Do away with single seat districts, proportional representation and return to a house where a congress critter represents no more than 450000 (George Washington wanted ~25,000) citizens.

This is the best evidence yet the size of the House is too small. Of course, the last people who have any interest in increasing the size of the House is the House membership. And well, we already know why most partisans aren’t interested either.

I’ll note again the philosophical difference I have with most others when it comes to government reform. The desire to change the system so that outcomes match the current partisan split is an inherently flawed way of looking at the problem. Changing the system to match factional interests – especially interests that are an inherently unrepresentative binary choice, isn’t going to result in better or more representative governance IMO. It should work the other way around.

And if one is concerned with actual representation, then the two-party system is what has to go – or else ditching it at least needs to be part of the total reform picture. Moving governing institutions toward 50+1 rule while maintaining an unrepresentative two-party oligopoly where the parties are open to capture by the fringe (see Donald Trump) is a recipe for disaster.

@Andy:

This is much more Steven’s wheelhouse than mine but two parties is almost a natural byproduct of single-member districts.

@James Joyner:

I’ve stated here many times before that I would prefer a multi-party system because, for my entire adult life, neither party has represented my interests. The problem is how to get from here to there.

I don’t think you do that by viewing representation through the lens of our binary system. Even in the post he just put up, Steven still talks about representation only in terms of the two parties and their relative representation. This is what I think is a mistake because the two parties are not actually representative of the people. We should not be changing the system to try to align it with this unrepresentative binary choice or making it structurally easier for one faction to get what it wants. Such changes would be fine if we had a multiparty system, but we don’t. I think they will be a disaster as they’ll only make the negative kinds of factionalism worse, especially combined with the trend of making everything a federal issue that needs to be managed from Washington.

@Andy:

Agreed.

@James Joyner:

Single-seat districts tend to lead to fewer parties, although not necessarily rigid bipartism (e.g., the UK). Single-seat districts plus primaries, in my view, create our two-party duopoly.

But to Andy’s point: we need a system that would encourage multi-party competition, and single-seat districts hamper that development for sure.

@Andy:

I do that based on the political reality of our system and politics. I figure that if people can’t understand how our current system distorts representation on its own terms, then there isn’t going to be much interest in reform. Put another way: I think that it is important to get people to understand that our current system doesn’t even represent our current parties well.

Your comment is interesting to me, because it suggests you think I have been advocating for simply better calibrating our current system, which is not the case and never has been.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Just as a matter of fact (and please do not read this as defensive, but rather simply as corrective): I would state that this is simply inaccurate. I have frequently discussed that what we need is reform that leads to multiple parties.

@Steven L. Taylor:

This gets back to what I think is the real problem – our parties – and where I think we differ.

We’ve had the same structure for a very long time and it produced stable governance that the American people thought was sufficient representative.

What’s changed is our parties (and probably ourselves), primarily since the 1990’s, but the roots go back to the creation of primaries two decades before that and the defenestration of any central party leadership. The disagreement I have is that structural change such as getting rid of the filibuster, or “democratizing” the Senate, etc. doesn’t actually solve the problem that primaries and weak parties created and it doesn’t solve the dysfunction of the two-party system. Rather it does the opposite – it incentivizes all the current problems with the two-party system by promoting factionalism and disincentivizing compromise.

I don’t think that is working out so well, so I’m skeptical of solutions that would further cement partisan interests and factionalism.

@Steven L. Taylor:

I don’t read that as defensive at all, and I know you have talked about reforms leading to multiple parties – and I share your goals on that front, as I’ve stated many times.

But I think it’s fair to say that the bulk of your posts and some of the positions you’ve specifically advocated for (like packing the Supreme Court) frame these issues strictly in terms of partisan representation relative to partisan votes. I think the level of effort you give to discussing representation at the party level is much higher and more frequent than the effort given to representation at the level of the American people generally. At least that’s the way I perceive it.

Regardless, my position is that improving representation at the party level ultimately solves nothing unless it includes real multi-party competition. Making government more “representative” of partisan interests in a binary-choice system doesn’t do that.

@Andy:

At the risk of drifting off-topic, modifying the modern filibuster arguably incentivizes compromise, at least at the edges. It would make peeling off a few votes from the minority party far more important than in the current system (especially if we are assuming that there will not be unanimous majority party votes on every issue.

@Andy:

To be fair, the posts to which you are referring are in the context of potential short-term reform. Indeed, in my posts on court expansion, I thought I was pretty explicit that I came to that position because it is a doable reform, rather than the more comprehensive reforms that I would prefer, but that seems impossible.

I will confess to some bemused frustration here: when I talk about more ambitious reforms I am frequently accused of asking only for pie-in-the-sky reforms that will never happen. Now you are telling me that I have been focusing too much on reforms that are more in line with current political conditions. 😉

@Andy:

Stable governance, yes.

And that the American people thought was sufficiently representative, yes.

But, of course, we have only had true universal suffrage in terms of the law since 1965 and an ongoing struggle to actually have it in practice since that time. There is that whole can of worms that has to be taken into consideration in any such assessment of the representativeness of American politics.

Beyond that, as you yourself note, you have long felt unrepresented.

I very much think that while Americans “thought” they were well represented, they were incorrect to think that.

@Andy:

I think that the choice we face, in terms of do-able outcomes is this:

1. Keeping the current structure of the Senate and pretending like it incentivizes compromise

or

2. Let the parties govern by basic majority rule when they have majorities (while recognizing there are broader representational problems in the system).

In re: point #1: there is no empirical evidence that suggests the filibuster, et al. is incentivizing compromise. It is a game of “let’s play pretend” to maintain the status quo for that reason.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Fair point. I would counter that I think the short-term reforms you advocate for either aren’t reforms at all or will make the problem worse. It’s not that I’m against short-term reforms, it’s that I’m skeptical of most of those you specifically advocate for. As the saying goes, “first, do no harm.”

An example:

Packing the court is not “reform” in any real sense of the meaning of the word, and few except political scientists would view it as such.

And the irony is that call for packing the court as a short-term “reform” is the direct result of another “reform” – ending the judicial filibuster.

I have no fondness for the filibuster, but it is not “democratizing” the Senate, it won’t make our politics better, it won’t incentivize our parties to compromise. Judicial nominations are the relevant example of what I’m talking about. If you want to argue that ending the filibuster for judicial nominees has resulted in an improved judiciary, then I’d really would like to hear that argument. I don’t see it.

My view is that it resulted in an asymmetry in the SCOTUS. To think that similar asymmetries won’t happen with the end of the legislative filibusters seems like wishful thinking at best.

I could go on, but I hope you get the point. I am very much for reform, but I’m a small “c” conservative on this in the sense that I don’t like reform for the sake of reform – I want some evidence that the reform will produce positive results. Which I’m not seeing.

On the long-term stuff, I share your goals but the question is how does one get from here to there? Wishful thinking won’t cut it.

That’s why I favor reforms like expanding the House and improving our parties – they are in the realm of possibility and would demonstrably improve things.

My view on bigger, longer-term changes is that reform must come from the states instead of hoping for some kind of imposed change at the federal level. Any state has the authority, for example, to make multi-seat districts. There is nothing in the Constitution that requires states to have geographical boundaries when choosing representatives for the House.

@Steven L. Taylor:

At this point, I agree it doesn’t incentivize compromise. That change is not because the filibuster changed, it’s because our parties changed. Again, I have no love of the filibuster, but getting rid of it doesn’t solve the problem.

I think that giving parties plenary power to enact their agendas without opposition works in a multiparty system or in our old system where parties were bigger tents with central party control. We don’t live in that world.

Instead what we will get is zero action on anything when the government is divided, and then when the dice roll gives one party control of all three branches they will maximize their advantage while trying to undo everything the other party did. So our governance will flip-flop 180 degrees every few years with nothing happening in between. If you can explain how this is an improvement, will result in better outcomes, better representation for the American people, and better governance then, again, I would really like to hear that argument. Because I don’t see it.

BTW, I’m enjoying this debate but may not be able to get back to it until tomorrow due to real-world commitments. So, I won’t be able to respond to anything for a while.

@Andy:

Andy, I’m having a real problem with seeing this as an either-or. The fact is that the 1974 change to the filibuster killed the “talking filibuster” and allowed the Senate to continue to business while a filibuster was happening definitely plays a role in facilitating the change you are talking about.

Looking at the filling of Cloture votes, there’s an immediate jump and a steady increase beginning around the change in rule set: https://www.senate.gov/legislative/cloture/clotureCounts.htm

Admittedly the largest jump comes with the election of Obama and McConnell and the Republicans radically expanding the use of filibusters to block majority party actions. That exploitation of the 1974 reform had a reflexive effect in further drawing a wedge between the parties (and assisted further in the rise of negative partisanship).

@Andy:

Well, if you are going to ask someone how to categorize politics… 🙂

In my view, expanding the size of a body (adding seats to the House or to SCOTUS) reforms that body by definition, regardless of whatever other ways it could also be described.

(I am trying to find amusement rather than vexation in the fact that I am constantly told that I should cleave more to popular understandings of words rather than to the understanding of the profession that studies the phenomena under discussion).

@Andy:

Well, a) I am not sure if our parties ever had central party control (although presidential nominations were more centrally controlled prior to 1972, but not congressional nominations).

and, b) I think the “big tent” metaphor is not super usefulness, insofar as by definition any two large parties are coalitional by nature. The difference is that the parties are more polarized and sorted. The long-tail effects of Reconstruction are over and are unlikely to change any time soon.

@Steven L. Taylor: I hit “post” too soon.

The notion that doing away with the filibuster leads to “giving parties plenary power to enact their agendas without opposition” is simply false, given the remarkable number of veto points in our overall system, as well as other structural components I write about constantly.

And I do not understand what you mean by “without opposition”–that is what elections are for.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Well, you made me smile with this one, anyway.

I found it interesting during the Wisconsin gerrymander case that got to the Supreme Court that the Wisconsin Democrats stipulated that there was a “natural” gerrymander. IIRC, the stipulation said that under a fair system they would have to win about 53.5% of the (combined Democratic and Republican) votes statewide in order to get their expected outcome up to 50% of the state legislature’s seats. This was due to Democrats packing themselves into the more urban areas, and the Wisconsin requirement for preserving communities of interest.

My own state’s constitution also includes communities of interest language and is supported by voters of both parties. At the federal level, Denver doesn’t want to give up having its own Congress person. Neither do the farmers and ranchers in the eastern plains portion of the state.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Got work done a bit early and have some time before I go get my first Covid shot (yay!).

And I am trying to find amusement rather than vexation that your responses avoided my main points and instead focus on quibbles about definitions. 😉

Fundamentally, though, the reality is that “popular understandings” are what’s important in the actual practice of politics, particularly when it comes to the legitimacy of something that is labeled as “reform” which I think most people understand is definitionally about improving the status quo. And what one considers an “improvement” is subjective.

Central control was a bad word choice on my part. I mean to emphasize a point I think we both agree on, which is the weakness of parties today compared to what they used to be, especially compared to parties everywhere else, particularly peer democracies. The parties used to have a sort of “peer review” when it came to platform and candidate selection that is absent today.

I’m not sure what a better metaphor is, but if you have a suggestion, I’ll take it. I hope you understand the point, however, which is that parties have not only polarized, but their interests have also narrowed, which is what ideological polarization tends to do.

And which of these veto points stopped the Republicans from packing the courts without opposition during the Trump Presidency after the filibuster was gone?

This is one core of my argument that you didn’t address. We have real-world experience with what happened when the filibuster was eliminated for judicial nominations. That “reform” resulted in an asymmetry that the GoP took advantage of – an asymmetry that would not have been possible were the filibuster still in place and one that resulted in you supporting court-packing as a corrective measure.

Again, to be clear here, I’m not trying to defend the filibuster in the way that most do as some grand and storied tradition about bipartisanship and that claptrap. I am not invested in the filibuster one way or another. I’m simply skeptical of arguments that claim eliminating it will be a net positive for our government and the country.

@mattbernius:

Sorry I missed your earlier comment and didn’t respond:

After reading this and my responses to Steven, let me try to come to my point from another direction:

Fundamentally I think it’s about evaluating the alternatives and their effects. We can:

– Keep the filibuster as is

– Retain it but with modifications

– Get rid of it entirely.

So for each of those cases, advocates for any position should be able to answer these questions:

– What is the purpose, the end goal?

– What are/will be the actual effects?

– What are the tradeoffs?

None of that is discussed, particularly the tradeoffs.

How did removing the filibuster for judicial nominees affect that wedge? Is there more or less comity in the Senate? At best, eliminating the filibuster didn’t affect the wedge at all, but I think things got materially worse as a result. My position is that I don’t think the results that come from eliminating the legislative filibuster will be any different. If someone here disagrees with that assessment, then – as I stated earlier – I would love to hear the argument.

@Andy:

Apologies for not responding in time. While this thread is over, I do want to respond with 2 points:

1. I’m not advocating for the elimination of the filibuster, but rather doing 2 things – first reducing the threshold to 55 votes for cloture (still a high bar for any modern party to pass in terms of representation) and second going back to the pre-1974 version where the filibuster has to grind the Senate to a halt (which would add more political ramifications to using it) and be done in a far more performative way.