Democracy Scholars for Proportional Representation

A lot of folks who study democracy have sent an open letter to Congress.

The NYT reports: Scholars Ask Congress to Scrap Winner-Take-All Political System.

In a sharply written open letter to Congress published on Monday and shared in advance with The New York Times, the scholars tell lawmakers, “It is clear that our winner-take-all system — where each U.S. House district is represented by a single person — is fundamentally broken.” They call on Congress to “adopt inclusive, multimember districts with competitive and responsive proportional representation.”

The list of signatories includes nine of the 18 living U.S.-based winners of the Johan Skytte Prize, a prestigious Swedish award that has become a kind of unofficial Nobel for political science: Robert Axelrod, Francis Fukuyama, Peter J. Katzenstein, Robert Keohane, David D. Laitin, Margaret Levi, Arend Lijphart, Philippe C. Schmitter and Rein Taagepera.

I was pleased to have been asked to sign this letter (one of over 200 to do so), and I fully support its contents. Of course, those contents will not be a surprise to regular readers of OTB.

As per the letter:

Because 90% of House members don’t have to worry about general elections and are beholden only to their district’s small number of primary voters, extreme elements are overrepresented to the point where one party in our two party system has been fully taken over by members that reject democracy itself.

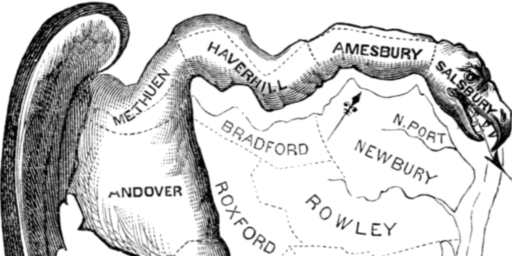

Contrary to popular belief, geography — not gerrymandering — is the primary cause of this districting crisis. As the country has sorted geographically, with Democrats concentrating in cities and Republicans in rural areas, it is often impossible to draw competitive single-member districts that offer any semblance of geographic continuity and that keep communities of interest together. In fact, maps drawn by nonpartisan commissions in this redistricting cycle had just as few highly-competitive districts as those drawn by politicians.

In simple terms, proportional representation means that a party would receive a share of seats in the legislature roughly equal to its popular support. This strikes me as definitionally more representative than our current system and by extension more democratic. Now, the devil is very much in the details. The exact process used, the size of the multiseat districts (in terms of the number of seats elected per district), the size of the legislature, and other factors would dictate how close the percentage of votes and seats would be (and also have a direct effect on the number of parties the system is likely to generate).

I would stress that “proportional representation” is not a system, but rather a result that can be generated by a variety of systems. I discuss some of these details in my posts Comparative Electoral Systems Basics and Speaking of Reform.

I know a lot of OTB readers remain skeptical of the concept (for a variety of reasons) but one objection frequently raised is that of fragmentation. Sure, two parties may not be enough, but Israel has so many! so QED, PR is a problem. First is Israel not a representative example of PR systems (it elects a single house from one nationwide district using a fairly straight-forwardly proportion process that is an outlier). Second, there are quite a few others, like Germany, that produce very different kinds of party systems. Another way of noting this is to say that not all PR systems are perfectly proportional (indeed, none of them are), so fragmentation can vary as the level of proportionality varies. Again, devils and details of the book-length variety.

Fundamentally I am an advocate for proportional systems for any number of reasons, including (but not limited to) the following:

- I think that in a representative democracy (which is what Madison meant by a “republic” in case anyone wants to go there) we ought to strive for actual representation. I suppose if one thinks that the current US system adequately represents the political interests of this population, one would be happy to stick with our system. But it seems pretty clear to me that it does not, hence my interest in reform of this type.

- I think that a system of elections ought to be truly competitive amongst those interests. Our system (as noted above) clearly is not. This is a major reason to be in favor of reform.

- I think that in a representative democracy politicians ought to be responsive to the voters. But if the system is not especially representative (point #1) and elections aren’t competitive (point #2), then there are few structural incentives for politicians to be responsive to general election voters. This is clearly a problem if one values the core notion of democratic governance.

I could go on (and certainly will in the future) but will stop there.

And yes, I know that reform is unlikely if not impossible in the long run, but just like climate scientists have had to take a long time (decades!) to make the public aware of the challenges of climate change, I think that a similar push from political science is needed here. And, as I have noted, some progress has been made. Indeed, a letter like this would not have been NYT-worthy a decade ago, I suspect. Still, I am no Pollyanna on this subject (not by a longshot). But understanding has to start somewhere.

Further reading from me on the problems of single-seat districts (only a partial sampling, in fact):

Thank you for a well-crafted and relatively complete and thorough case for this issue. But yeah, it’s not happenin’ any time soon, sad to say. The plea to “keep on keepin’ on,” if you will, is powerful in that context.

And here I was wondering why democracy scholars would suddenly be pushing statehood for Puerto Rick.

We have proportional representation. Republican billionaires donate more money than Dem billionaires and get proportionally more representation. (I’m not sure it’s still true that wealthy GOPs donate more than wealthy Ds, but it has been true, and the results, as they say, are before us.

Echoing Cracker, thanks. Well thought out, clear and concise, especially given the complexity of the topic. But again, not a’gonna happen given the pressure to maintain the status quo. “Hey, I’ve got mine, the rest of you can eff off.”

I support the sentiment and generally the goals – I remain skeptical of the process and continue to think that Steven and others do not sufficiently consider the risks of dismantling the present system.

@gVOR08:

I was wondering what sort of Public Relations these scholars wanted for/from Congress (seriously).

@Andy:

This is a legitimate area of concern. But since it is still necessary to get people to simply understand the nature of the problem it seems an order of operations problem to spend a lot of time on the downsides of change.

@Mu Yixiao:

@gVOR08:

When I saw the headline, I first went to “public relations” and then to “Puerto Rico” before finally ah-ha-ing “proportional representation”. Great minds?

@Steven L. Taylor:

I use marriage as an analogy for this.

The current Constitution is our marriage contact that we the people, are married to for better or worse.

But now we are past middle age (in terms of the length of nations), and our spouse isn’t as attractive anymore and the habits that were once revolutionary or were necessary compromises have gotten tiresome. We look around and see all the other marriages (Germany, Israel, ect.) that are better looking, in better shape, and more attentive to our needs and we imagine how much better life would be if we weren’t stuck with what we have.

The problem is that getting a new spouse is really difficult. First, you must divorce your current spouse, which is messy and expensive. That may be fine and worth it if you have a better match waiting in the wings that you’ve already been courting.

But this is where the analogy falls down. We can’t have a better spouse waiting in the wings when it comes to the Constitution. Instead, we have to rely on matchmakers (Congress and the States) to create a new marriage as it dismantles the previous one. That’s an emergent political process that can’t be predetermined. If we embark on this course, we have to hope that the new marriage will be better, but we don’t know. And I look at who is in Congress and running most of the states and believe that those are probably among the last people on earth I would trust to rewrite the Constitution.

If we could, instead, put you and all your colleagues who signed the letter in charge of this process, then that might be cause for hope. But that won’t be how it works.

So here’s the problem I have with what you are doing – you’re delegitimizing the current marriage and attempting to convince people it’s bad, but you don’t have any plan to annul the current marriage (in fact, you admit it is politically impossible), nor do you have any means to ensure that what comes next will be better.

When our current Constitution was written, it was originally supposed to be just some reforms to the articles of confederation. That Pandora’s box was opened and we are lucky we got something that has endured through every crisis this nation has faced so far. You want to open that box again, but no one knows what would actually happen much less if the result will be better by whatever metrics you want to use to measure such things.

So if we are talking about the order of operations, then what do you actually expect to happen after you get people to “understand the nature of the problem?” You don’t want “to spend a lot of time on the downsides of change” but the fact is that change could be very, very bad. Hope is not a strategy.

So if you’re successful in delegitimizing the current system, it’s not guaranteed that will engender the political support to change the system, much less change it in the ways you and I would both prefer. I see two big risks here. One is the possibility that the mass political will to change the system won’t manifest even after you’ve educated people about the problem. In that case, we’d have a system that few see as legitimate but incapable of reform. I think that’s the path we are currently on. The end-state is that no institutional legitimacy is left, and politics becomes about competing mobs vying for power in a zombified Constitutional system.

To return to the marriage analogy, it would be like constantly telling your spouse how ugly and mean, and stupid they are and how much you’d rather be with your idealized mate. But that idealized mate only exists in your head, and you have to hope that third parties will get you a better spouse. But that may not even happen – you could just end up stuck in the marriage that you’ve helped ruin.

The other alternative is that reform does happen, but it’s bad. We’d be like a Latin American country, which we already resemble in many ways. I forget the numbers, but I recall that the average Latin American country rewrites its Constitution every 20 years or so.

So as much as I would like to see our system change, that is not a risk I’m willing to take. Until I can see a way to get from point A to point B or have some assurance that annulling the Constitution would bring about one that is better instead of one that is worse, I would prefer to settle for incremental improvements to the system we have and accept and promote it’s legitimacy, warts and all.

@Andy:

It is not at all clear to me why you are putting it on Steven as an agent delegitimizing the current system. The system has delegitimized itself as evidenced by the political dysfunction our system is currently producing. Dr. Taylor is merely pointing out the obvious, or if you insist on putting some of the onus on him, he is refusing others the luxury of hand-waving away the self-evident illegitimacy.

To leverage your marriage analogy, what if instead of berating your spouse for not being ideally nice and beautiful, you have hard evidence that your spouse is a sleeping with a mobster and abetting him in his crimes? (For my money, criminal behavior is a much closer analogy for anti-democratic Trumpism in the marriage scenario than mere meanness and ugliness.) The horrendous nature of your spouse doesn’t increase in any meaningful way the odds of you finding a better, let alone ideal, future partner. But to stay in that marriage on some wishful hope that you might convince them to be a better person would be naive in the extreme and likely self-destructive.

As you note, it comes down to the question of acceptable risk posed by the change. But, that assessment of risk needs to equally clear-eyed regarding the danger present in the status quo. These leading thinkers in the world of political science are urging you to see just how bad our current system is. I would urge you to be open-minded enough to consider they could be right.

@Andy: Suppose you have a friend who is in a horrible marriage but is insistent that the marriage they have is ideal despite all the problems. You try to tell them that most other marriages are not like their marriage and that there are ways to radically improve their existing marriage. That, indeed, there are a lot of really great examples of marriages in the wide world that they could emulate.

The letter does not ask for a divorce. It points out one very significant area of potential reform that could be done without tossing the entire system.

@Andy: I didn’t have time to finish my thought from earlier.

The proposal is to change one aspect of the system. How is that “delegitimizing the current marriage”?

Quite frankly, the more I think about it, the more flawed your analogy is. This is not about wanting a prettier, nicer spouse, this is about wanting a functional relationship that fulfills the basic promises f a marriage.

(And the more I try to work with this analogy, the more I struggle with who is married to whom, making it a bit strained in my mind).

I would note that shifting the elections for the US House to a PR system would be an incremental change definitionally. It may be more dramatic than you prefer, but it is incremental. It does not change the structure of Congress, separation of powers, or of federalism. It is hardly, to go back to your analogy, a divorce. It isn’t even a separation.

Beyond that, how do you think that we get any kind of incremental change (perhaps something like expanding the size of the House to match population growth) if you don’t talk about the problems inherent in the current system?

The notion that having these conversations is delegitimizing is a curious one, in my view.

@Scott F.:

Indeed. 🙂

@Andy: In the name of fairness, I will agree that exploring the implications of reform, including the potential negative consequences, is a legitimate part of these conversations.