Reporters as Truth Arbiters

How far should the press go in challenging assertions by politicians?

Public editor Arthur Brisbane created a firestorm yesterday when he asked for reader input as to “whether and when New York Times news reporters should challenge ‘facts’ that are asserted by newsmakers they write about.”

One example mentioned recently by a reader: As cited in an Adam Liptak article on the Supreme Court, a court spokeswoman said Clarence Thomas had “misunderstood” a financial disclosure form when he failed to report his wife’s earnings from the Heritage Foundation. The reader thought it not likely that Mr. Thomas “misunderstood,” and instead that he simply chose not to report the information.

Another example: on the campaign trail, Mitt Romney often says President Obama has made speeches “apologizing for America,” a phrase to which Paul Krugman objected in a December 23 column arguing that politics has advanced to the “post-truth” stage.

As an Op-Ed columnist, Mr. Krugman clearly has the freedom to call out what he thinks is a lie. My question for readers is: should news reporters do the same?

On first reflection, this struck me as a perfectly reasonable question and two very good examples. My instinct is that neither of these cases call for reporters to directly challenge the “facts,” since the assertions aren’t falsifiable. Rather, reporters should simply report what was said and, in the case of controversial political assertions, also report that the interpretation is in dispute.

As the debate has unfolded, though, I’m less sure as to how far that should go.

In a follow-up post last evening, Brisbane observed,

I must lament that “truth vigilante” generated way more heat than light. A large majority of respondents weighed in with, yes, you moron, The Times should check facts and print the truth.

That was not the question I was trying to ask. My inquiry related to whether The Times, in the text of news columns, should more aggressively rebut “facts” that are offered by newsmakers when those “facts” are in question. I consider this a difficult question, not an obvious one.

He also included a reply from NYT executive editor Jill Abramson stating, in part,

Of course we should and we do. The kind of rigorous fact-checking and truth-testing you describe is a fundamental part of our job as journalists.

We do it every day, in a variety of ways. On the most ambitious level, we sometimes do entire stories that delve into campaigns to distort the truth. On a day to day basis, we explore the candidates’ actions to see if what they’ve done squares with what they are saying now . . .

[….]

And providing facts to challenge false or misleading assertions isn’t just part of political coverage. We do it routinely in policy stories from Washington and business stories from Wall Street. We do it in science coverage, too — for example, we constantly point out the scientific consensus on climate change,

Of course, some facts are legitimately in dispute, and many assertions, especially in the political arena, are open to debate. We have to be careful that fact-checking is fair and impartial, and doesn’t veer into tendentiousness. Some voices crying out for “facts” really only want to hear their own version of the facts.

This was not good enough for most commenters, though, who think that, by trying to be “objective” and avoid charges of liberal bias, the mainstream press has gone too far and become mere “stenographers.”

American Journalism Review‘s Rem Rieder argues for “Real Time Fact-Checking.”

Allowing a politician to get away with nonsense day after day lets false statements seep into the public consciousness. Once that happens, it can be hard to dislodge them. And the separate fact-checking piece, while incredibly valuable, is an imperfect antidote.

Questionable claims should be challenged as quickly as possible. Sometimes that will be possible in a first-day story. Sometimes it won’t. In the latter case, once they have run separate assessments of the claims, news outlets should replicate the findings when the allegations come up again. Because so often they do.

If the Times goes this route, as I hope it does, Brisbane wonders if the paper can do so “in a way that is objective and fair.”

Sure it can. How? By being an equal-opportunity scold. Hold everyone to account, whether it’s President Barack Obama or Mitt Romney or Ron Paul or Newt Gingrich or the local candidate for mayor. A clearly partisan take would be disastrous. A straight-down-the-middle approach would be an immense public service.

But this is easier said than done.WaPo’s Greg Sargent asks pointedly, “What are newspapers for?”

Should news reporters include that last paragraph giving readers the information they need to evaluate whether Romney’s claim that Obama “apologized for America” — which the paper itself is amplifying — is true?

I’m sympathetic to Brisbane’s worry that that regular fact checking by reporters could mean some statements will get checked and others won’t. (Although as Jamison Foser neatly illustrates, newspapers are already choosing which quotes to amplify and which ones to ignore, which itself throws into question whether total “objectivity” is possible.)

But I think there’s a simple way to drive home to Brisbane why reporters should include info enabling readers to judge such claims.

The Times itself has amplified the assertion — made by Romney and Rick Perry — that Obama has apologized for America, without any rebuttal, at least three times: Here, here, and here. I urge Brisbane to check them out. If he does, he’ll see that any Times customer reading them comes away misled. He or she is left with the mistaken impression that Obama may have, in fact, apologized for America, when he never did any such thing.

In other words, in all those three cases, the Times helped the GOP candidate mislead its own readers — with an assertion that has become absolutely central to the Republican case against Obama. Whatever the practical difficulties of changing this, surely we can all agree that this isnot a role newspapers should be playing, particularly at a time when voters are choosing their next president.

The problem with this is that the “apologize for America” trope, while tired, has a real basis in fact. As someone who will probably vote for Romney over Obama in November given that choice, I think it’s a cheap spin on Obama’s record. But the “apology tour” meme came about in real time from a series of speeches given by Obama early in his administration which, in my judgment, did come across as too apologetic.

Back in June 2009, Heritage’s Nile Gardiner published a list of “Barack Obama’s Top 10 Apologies: How the President Has Humiliated a Superpower.” Most of them strike me as weak tea, at best, but a handful of them are genuinely apologies. As Romney explains in the book which kicked off his campaign,

In his first nine months in office, President Obama has issued apologies and criticisms of America in speeches in France, England, Turkey, and Cairo; at the CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia, the National Archives in Washington, D.C., and the United Nations in New York City. He has apologized for what he deems to be American arrogance, dismissiveness and derision; for dictating solutions, for acting unilaterally, and for acting without regard for others; for treating other countries as mere proxies, for unjustly interfering in the internal affairs of other nations and for feeding anti-Muslim sentiments; for committing torture, for dragging our feet on global warming and for selectively promoting democracy.

PolitiFact rules that, on balance, this is incorrect. But it’s mostly because Obama never used the words “I’m sorry.” What he did say, though, certainly comes across as apologetic. He told a French audience that the United States “has shown arrogance and been dismissive, even derisive.” On the war on terror, Obama proclaimed that ”our government made a series of hasty decisions. I believe that many of these decisions were motivated by a sincere desire to protect the American people. But I also believe that all too often our government made decisions based on fear rather than foresight; that all too often our government trimmed facts and evidence to fit ideological predispositions.”

Now, I’d argue that these statements are defensible, if not objectively true. Further, I think there’s a subtle distinction between “apologizing for America” and rejecting as unwise the policy positions of her previous leaders. That’s especially true if one takes the speeches in their fuller context rather than cherry pick the passages where he tries to be conciliatory towards his audience. But it’s perfectly understandable that others would perceive this as part of an “apology tour.”

My preference in these instances, then, is for straight news reporters to simply but succinctly note that the assertions are in dispute. Presumably, some Obama administration official has gone on the record taking exception to the “apology” meme. Briefly note that and move on. (At least, that’s how a print story should be handled. For online stories, it’s possible to reference and hyperlink longer expositions on the dispute at hand in a way that doesn’t detract from the story.) Otherwise, a story about actual news–what’s being said on the campaign trail that day–gets hijacked by the reporter’s analysis of Romney’s opinion about something Obama said three years ago.

At the same time, though, there’s a difference between genuine differences of opinion–where I think the “apology” example fits–and outright lies. For that matter, there’s a distinction between silly lies that politicians tell on the campaign trail to give partisan crowds the red meat they came for and serious lies about grave public policy issues.

I agree with Glenn Greenwald that a press corps that’s too credulous, simply reporting assertions made by public officials, can become propaganda outlets for the government.

Every day one can find prominent news articles that are shaped entirely by the following template: A, B and C are true, say anonymous American officials; government claims drive the entire article and shape its narrative, with “officials say” tacked on as an afterthought, an unnoticed formality. In the realm of reporting on the government, this practice encourages and enables government lies; in the realm of political reporting, as Greg Sargent’s examples show, it incentivizes candidates to lie freely.

But there is one important caveat that needs to be added here. This stenographic treatment by journalists — of simply amplifying what someone claims without any skepticism or examination — is not available to everyone. Only those who wield power within America’s political and financial systems are entitled to receive this treatment. For everyone else — those who are viewed as ordinary, marginalized, or scorned by America’s political establishment — the exact opposite rules apply: their statements are subjected to extreme levels of skepticism in those rare instances when they’re heard at all.

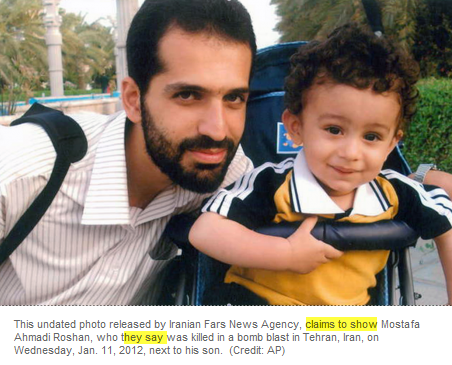

He points to a caption on an AP photo of the Iranian nuclear scientist killed in a car bomb the other day and notes that it caveats everything:

Greenwald thinks this is as it should be:

Extreme skepticism oozes from every pore of that photo caption. AP refuses to accept that this scientist was killed; they even refuse to accept that this is an actual photograph of the scientist in question and that the photograph shows him with his son. Instead, AP wants you to know that even these pedestrian assertions are nothing more than unverified “claims” from Iran’s state-controlled media and thus cannot and must not be assumed to be true.

I have no problem with that type of skepticism. To the contrary, it’s warranted; as I.F. Stone famously taught, the only thing journalism students need to know is that “all governments lie.” But the point is that one would never, ever see this level of overt skepticism from AP or any other establishment media outlet when it comes to claims from the U.S. Government. Instead, those claims are treated as presumptively true; in fact, they’re so trustworthy that entire news stories can be written that do little more than adopt those government claims as the dominant narrative (“The drones would be cleared to fire on a senior militant leader if there was credible intelligence and minimal risk to civilians, American officials said“).

It seems to me that this is a much cleaner case than the Romney quote. Whether the person in the photo is actually the Iranian nuclear scientist is a verifiable fact; until it’s verified, caveating is warranted. Similarly, reporters have an obligation to find out the truth about important stories like the American drone war in Pakistan. To the extent that they can verify statements made by US officials, they should of course do so.

At the same time, however, reporting on breaking news comes under deadline pressure. Oftentimes, all reporters have to go on in the initial hours and days are statements, photos, and other information that come from government sources. That means that such stories will have little choice but to rely on those sources in describing the events. Ideally, stories about national security policy will be run through a filter of skeptical journalists who actually know the beat. Further, subject matter experts in academia, think tanks, and the like–including those who previously served in government–should of course be asked to comment on the likelihood of the official version of facts being correct.

That actually does tend to happen. Of course, as Peter Singer outlined in detail back in August, there’s the wee problem that many “think tanks” are actually just propaganda outlets for one party or ideological cause. Pretending otherwise is one of the real places where journalists do practice stenography.

Charles Pierce has a good follow-up at Esquire, particularly the second paragraph:

http://www.esquire.com/blogs/politics/new-york-times-public-editor-on-truth-6638107

I’m afraid I have to call BS on this phraseology:

When you go with “basis in fact,” you dodge “is true.”

You could also say, on a deeper level, that the US can afford a little shallow self-criticism, when it doesn’t, actually, include a meaningful change in actions.

I mean, you are big on Obama’s foreign policy being Bush’s 3rd term, right?

There is a little bit of a disconnect to get agitated then about an “apology tour,” unless you’d just like that 3rd term, minus the introspection.

“As someone who will probably vote for Romney over Obama in November given that choice”

Not entirely relevant to the overall post but I find this fascinating. Why would you vote for someone who believes in nothing, stands for nothing, panders to whomever it takes and is pretty much a pathological liar? All in the name of being President.

Ron Paul might be nuts, but at least he believes the nonsense he spouts as does Santorum.

Mitt is an utter joke.

@john personna: I don’t think it’s a factual statement, but rather a reactive one. A few of the statements are clearly apologetic, in my judgment, but only mildly so.

@john personna: Obama’s foreign policy rollout was that of a neophyte and was somewhat irksome to me. On balance, though, I think he’s chosen mainstream policy positions that continued on the path that Bush put us on starting in 2005-2006.

@TheColurfield: I distinguish between Romney the campaigner and Romney the adminstrator/governor. Like George HW Bush, he’s pretty hamhanded in the former role. He’s been quite competent in the latter.

Probably because in the end there is not much daylight between Obama and Romney policy preferences if I had to guess. Sure, one dude’s black and used to organize communities, and the other one was born with a silver spoon in the mouth and worked in vulture capitalism (God I like that phrase), but no, not much daylight at all.

I’m not being sarcastic either.

It’s perfectly understandable that they don’t perceive subtle distinctions in the wider context of a foreign policy speech? I mean, sure, but we don’t want people to misunderstand things out of proper context. We want to encourage them to think more broadly about what their politicians are saying. That way, they’d be better at catching the bullshit.

This is where the stenography of the media comes in, because it’s easier to write and sell news to less-critical people. They accept the basic statement “he apologized for America,” which to me is false without the caveats you mentioned. The news media doesn’t draw attention to this, and it becomes de facto truth in our discourse and repeated as such.

@James Joyner:

There is obviously a difference between saying “Obama seemed too apologetic to me” and “Obama apologized for America.”

The former is clearly subjective, while the second frames itself as a factual assertion. I think that’s the key in the discussion above, and that’s why PolitiFact ruled the way it did. It isn’t just a nit that Obama didn’t say “I apologize.” It’s a big thing that critics are speaking from their subjective response.

Put another way, if you heard the two phrases “Obama seemed too apologetic to me” and “Obama apologized for America” you might have very different expectations for what the unquoted text, what Obama actually said, looks like.

I’m sure there are thousands of Americans out there right now who do think Obama said “I apologize” because they’ve heard he “apologized for America” so many times.

Very nice post, Mr. Joyner. A pleasant read.

I have one word on the topic of stenographic journalism: Death Panels

Hey Norm,

Exactly. The death panel charge was false, every journalist knew it was false, and yet the so-called liberal media never called the Tea Partiers on it.

How are these statements untrue? As for them seeming “apologetic”, I guess they might appear that way to anyone who agreed with the bellicose, ham-handed words and actions of the Bush Administration…

@ Moosebreath…

I also believe you have to entirely ignore context and meaning to claim Obama apologized for the US. But the examples are many…and the central issue…that journalists today are glorified stenographers…is accurate.

I’m with you on this, James. Nobody is compelling the news outlets to publish every utterance of any politician. If they’re functioning as propaganda outlets for dubious assertions by politicians, it’s the news outlets’ own damned fault.

One problem I see with the news outlets’ attempts to fact-check statements rather than merely reporting (or not reporting) what happened is I don’t see any clear way for them to distinguish between facts and matters of opinion. Recently, there have been any number of dubious attempts by the NYT and others at fact-checking things that are simply matters of opinion so I’m not just raising a hypothetical.

Having been misquoted for the nth time this week by a newspaper, I would like to see papers first getting the facts right and secondly doing more stories. I can’t help but think this additional service would be at the disadvantage of these more important functions.

@Dave Schuler:

I think the English language is quite robust, and can convey the distinction in any circumstance.

And certainly any journalism school graduate should know how to use the language to convey both fact and opinion.

(Perhaps your confusion is that there are areas where there are no underlying facts, only dueling opinions. That is often the case, for instance, in macroeconomics.)

Oh, I don’t know. Unless they want to look like slobbering fools they could apply as much diligence to one candidate who asserts an unrepentant terrorist is just ” a person I see in my neighborhood from time to time” or ” my political God father is Emil Jones” or ” I didn’t hear the black activist sermons of Rev Wright” as they apply to other candidates.

It’s a start.

Is “green energy” cronyism getting the same play as “bushes oil buddies?”. How about recess appointments?

I could go on. The “media” have the right to conduct themselves any way they want. But that does not confer legitimacy to t heir reporting.

So? Was there any shakeout to that right wing paranoia? Do we have a Black Panther government or something? The closest I can see is Predator drone attacks on Muslims, which is probably not what had you worried.

People on the right and the left oppose energy subsidies, including the green kind. It’s not an active story, but it’s not a secret.

Likewise, no secret.

@Dave Schuler & @PD Shaw —

One problem faced by newspapers (and other news outlets) is that there are really three tiers – Big city/Regional/National, Small/Midsized, Community. Of those three, it’s typically only the first that has any significant fact checking resources. In some cases, midsized city newspapers are part of a network which will do “fact-checking” on the national level.

Generally speaking, the latter two are running full steam to produce a daily/weekly. As such, its unfortunately far more “catch-as-catch-can” than the journalists would like. But that’s life in the small/midsized city.

While I agree with James that it’s a matter of degree, I also understand and sympathize with the outpouring of frustration by Times readers. Nothing illustrates my frustration with his paper than their ongoing refusal to state that President Bush lied when he said “America does not torture”. That is objectively and demonstrably false, yet to this day the Times will call the exact same action “enhanced interrogation techniques” when we do it but “torture” when done by anyone else.

It really isn’t true that Obama apologized for “America”.

He apologized for something a bit more specific. It’s the journalists job to demand Romney explain what he is talking about, or point out that exactly what he is referring to is unclear, rather than label the whole thing true or false.

If the Times can’t point out things like “government takeover of health care” or “death panels” are not true, then what good are they? And not only do they have to do a fact check of those statements initially, they need continue to point out those statements are lies, or not print them.

That is a good question, and I would like to see an answer. Don’t expect too though.

When President Reagan honored unrepentant terrorist Menachem Begin at the White House I don’t recall any conservatives whining about it. Bottom line is some terrorists manage to reintegrate themselves into society. Can’t you do any better than parroting dumb-as-a-rock Sarah Palin?