Sullivan on Biden (and a Discussion of Fiscal Policy)

On fiscal policy and historical comparisons.

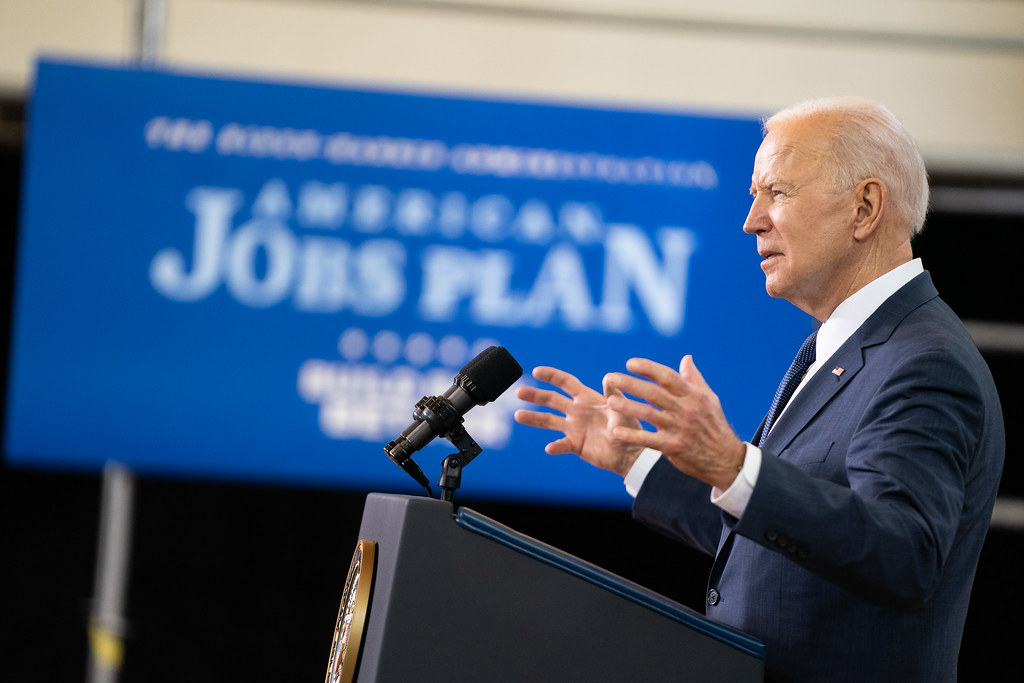

Andrew Sullivan has an interesting essay on Biden’s speech to Congress that is worth a read (The Strange Fate Of Joe Biden: The unlikeliest would-be revolutionary in American history). His basic thesis is as follows:

who ever would have thought that a) Joe Biden, of all people, would one day be president; b) that he would be elected with slim Democratic majorities in both Houses after a close election; and c) that he would then unveil the most brazenly leftist, spend-and-borrow agenda of any president since, er, Nixon? I mean seriously. Until a couple of years ago, I sure didn’t.

The jury is rather obviously still out as to how successful Biden will be with his agenda so some of the more grandiose discussion about how to view his presidency is premature. However, there is no doubt that it is far more ambitious than many (myself included) expected. Still, I think Sullivan is correct to note that Biden actually has a decent chance at success.

Today’s huge swing leftward is therefore in part a consequence of the GOP’s abandonment of fiscal conservatism. I mean: if the GOP can gleefully borrow trillions to give the plutocrats a handout during a boom, why can’t the Dems do the same to pay for childcare and education for those struggling in the wake of an American pandemic?

I find myself with the Democrats on this. If debt really no longer matters (as we are now unpersuasively told), I’d much rather the money be spent on the 99 percent rather than the one. And that’s especially the case after a long period in which economic inequality has gone far beyond what most liberal democracies can long survive; after the costs of middle-class life, from education to healthcare, have exploded; and after a plague has made effective government much more appealing — with the vaccine effort as the most tangible current example. Biden is riding this tide, and he’s been around long enough to know that it’s worth catching while he can.

Setting aside exactly how huge a swing leftward all of this is (I confess I find that description a bit much, but I take the basic point), the rest of this hits on some key factors. Indeed, the Republicans really have set the stage for this current moment and I would say there are at least three important elements to this fact. The first two are identified above by Sullivan and I will add a third below.

First, their own fiscal policy choices, as Sullivan notes, utterly undercut their main argument about Democrat desires for increased spending: that it costs too much and that we have to pay for it. If we just look at Republican behavior during the Trump administration, especially the two years of unified government, it is impossible to take their protestations about deficits and the debt seriously. This is made all the more true when one looks at the Bush administration’s approach to both Iraq and Afghanistan (and current GOP views on Afghanistan).

It is beyond arguing that when it comes to military actions and tax cuts, the GOP does not take deficit spending seriously (or, really, at all when they have a real chance to do something about it). There is simply zero intellectual foundation for Republicans to talk about deficits and the debt.

Zero.

Now, that doesn’t mean deficits and the national debt don’t mean anything, although at the moment they seem to mean a whole lot less than we thought they did. Note, for example, all the dire things that haven’t happened despite the rise in the debt (no inflation, no crowding out of private borrowers from the market, indeed very little negative impact at all). We have been told for quite some time that doom was nigh (this has been a central theme of conservative economics since at least the 1970s) and yes, no doom. Not even close to doom, in fact.

Ezra Klein discussed this with Paul Krugman on his podcast a month or so ago, and I would recommend that interview.

I will note this from Klein:

so the idea was, there’s a pretty mechanical relationship between high debt and interest rates. And then that relationship just does not come to pass over the past 10, 20 years when it’s being talked about a lot. I think it’s one term I’ve heard for it is untethered, that debt and interest rates untether.

And so one question I have is, was that ever right? Or was it simply a theory that was wrong? Did the world change or did the world simply disprove the theory?

And this excerpt from Krugman’s response:

The fact that interest rates are so low, it’s not just telling you that the government can borrow very cheaply. It’s telling you that the private sector doesn’t seem to have any good uses for the money. Interest rates are a little bit higher for business borrowing than they are for government borrowing but not much higher.

And with all that money available at very low cost, you would think that businesses would be going out there and building lots of factories and buying lots of software, and whatever. But they aren’t, which is saying that they don’t actually see great investment opportunities out there. Which means that, really, we have a overhang of or an excess supply, to use the jargon of savings.

And the government isn’t really competing with business for a pot of money. It’s really giving a pot of money that is looking for someplace to go, something to do with itself. And that’s way the world has changed.

That low cost for debt is really, really salient to the current debate. As Krugman also pointed out: “That the interest rate on debt is just consistently below the growth rate of the economy, which means that debt tends to melt away.”

Just go look at the yields on Treasury bonds and tell me that now isn’t the time to finance some national investments.

Fundamentally I arrived at where Sullivan is quite a while ago: if we are going to continue to deficit finance government and add to the debt (and we are) then spend on helping the citizens of the country:

So — why the hell not?— we have proposals for massive new spending on infrastructure; on childcare, medical leave, and expanded education; on technology and research; on ending cancer. After a while, you began to wonder what the federal government couldn’t give us, especially after we’ve seen it spend trillions and trillions with barely a glance at the cost during Covid. The sweet spot in Western politics right now is economic leftism and cultural conservatism. Biden has now clearly claimed the former.

At this point, if austerity is the approach only when it comes to things we need (health care, education, infrastructure, etc.) but not when it comes to defense spending, military actions abroad, and tax cuts for corporations and high earners, then why have austerity at all if we have not seen the dire predictions about the deficit ever come to pass?

I get the notion that there is some theoretical limit to all of this, but at a minimum, any data/evidence-oriented approach has to acknowledge that the dominant theory of the effects of deficit spending simply has not come to pass.

A second factor is the failure at basic governance during the Trump years as it pertains specifically to the pandemic. It is hard to objectively look at Trump’s policies in that area and state that he handled it well. And, this is a longer-term GOP problem as I would also include huge mistakes during the Bush years, e.g., Iraq, Katrina, and the build-up to the financial crisis, but since that is practically ancient history to a lot of people, I am not sure it plays in as much as it should.

The combination of the Republicans incoherence on spending and the failure of the previous administration, on Covid specifically, does present an interesting scenario for Biden.

Sullivan again:

His gamble is nonetheless similar to Reagan’s in this respect: he hopes that an economic boom will sweep away objections and caveats, and that Covid and Trump will indict conservatism as effectively as stagflation and Carter once indicted liberalism.

One can make too much of clever historical comparisons, but this struck me as interesting insofar as it has a certain ring to it. Reagan was successful, at least in part, because he both built off the failures (real and perceived) of the previous administration and presented a far more optimistic and appealing person vis-a-vis his predecessor. He also was able to use an eventual economic boom to solidify his legend. There are some potential parallels with the present moment. Biden has been the picture of competence and optimism in clear contrast with Trump (although yes, I know right-wing media is seeking to paint a very different picture, and they will succeed in doing so for their audience, I suspect). Biden has definitely over-performed vaccine expectations (and yes, some of that was clearly the result of engineered expectations, a sign of smart politics, IMHO) and the economy is doing well and appears poised to continue to do so. This will all redound to his credit with at least a majority of the population.

Of course, in these polarized times, none of this likely to sway many Republicans, especially not office-holders who see their re-elections as directly linked to pleasing the more ideologically oriented in their bases.

This leads me to the third factor: the Republican Party is not incentivized to compromise (or really, participate in these legislative initiatives). This means that really all Biden needs to do is work within his own party. Look at the passage of the Covid relief package. In the past, the opposition would have been able to force a lower price tag. But when the opposition is interested more in pleasing their base via rhetoric and when actual cooperation can get you in trouble with that base, the opposition actually takes itself out of the legislative game.

Put another way: if the Democrats have the votes to pass X legislation, what does it really benefit them to get less than X just so that they can say a few Republicans voted for it? If the bill passes, the bill passes. The number of opposition lawmakers who joined in passage does not make the bill more gooder.

A bill passed with zero opposition votes and one passed with all the opposition votes is the same thing: a law. And while people say they want bipartisan behavior in Congress, at the end of the day only nerds know (or care) the vote counts for passed legislation.

By not really wanting to help govern (and the Reps clearly haven’t since at least the first Obama term) means they are a non-factor in legislating.

None of this is to say any of this is going to be easy, given the way the Senate works and the fact that the 50 Democrat Senators are not all ideologically identical. But it does narrow the scope of negotiation. And if Republicans really want influence, they need to understand that. Their recalcitrance in this area may be what forces Manchin and Sinema to change their minds on the filibuster.

Sullivan makes a number of additional points on racial politics, many of which I would dispute, but this post is already long enough. Indeed, it was a quote on his tweet about the essay, which focused on race, that led me to click-through because I was wondering what he meant. I ended up ignoring most of that part of the essay, focusing instead on the fiscal policy issues.

In summary, I think that the politics of deficits have shifted, even if GOP rhetoric on the subject hasn’t. Further, the more Biden can look competent, the more the GOP’s recent record of problematic governance will haunt them. And, most importantly, just wanting to obstruct and look good for the base means losing influence in the legislative process for the Reps until 2023 at least.

I will add, since it is my main focus, that GOP behavior is sustainable in this way because the party is shielded in many ways from the democratic consequences of their positions because of built-in structural advantages in our system. This was illustrated yet again by the census results and pending reapportionment (and the commensurate effects on the Electoral College).

One can argue whether what Biden wants to do is a good idea of not, but one cannot deny that the Reps are shielded in many ways from accountability and therefore have no incentive to try and govern.

Republicans applying the Hastert Rule to Democrats as a self-own.

If there’s no point in Republicans passing a bill with Democratic votes, since it waters it down… what do they think will happen when they force that behavior on Democrats?

Manchin has exactly as much power as Bernie. As much as the Democrats have to appease Manchin and Sinema, they also have to appease Bernie and Warren.

A few Republican votes would cut Bernie’s power.

ETA: I got the edit function, and it seemed like a shame not to use it. I expect I don’t see some typo above that I could use this precious opportunity to fix and am squandering it.

@Gustopher:

Don’t get me wrong: more votes is better.

I am not arguing for a Dem version of the Hastert Rule.

I am arguing that the Reps have consciously taken themselves out of the process, which is affecting Dem strategizing.

Again: if Reps has been willing to give Biden a “bipartisan” Covid relief bill, they could have gotten the price tag down. But they weren’t willing to help Biden because they are incentivized not to help.

@Gustopher: @Steven L. Taylor: Upon re-reading, I see your point (and it is not the one I thought you were making).

So, while I stand by my above comment, I realize you weren’t saying what I initially thought you were.

To your point, I don’t think there is a critical mass of Reps in the Congress who really want to govern.

@Gustopher:

No, Bernie does not have as much power as Manchin or Sinema except in a sort of abstract way, but Bernie is not going to oppose any big safety net spending, and Manchin may. Theoretical power does not equal actual power.

Perhaps 10-15 Rs in the House and perhaps 5 in the Senate and among those are people like Toomey and Portman who aren’t potential votes on spending issues.

@Michael Reynolds: Yep. Political power migrates to those not reluctant to use it. Right now that is Sen Manchin.

@JohnMcC: No, not merely a willingness to use power, but having effective levers. Manchin’s desires are less negatively effected by a smaller or no deal than Bernie, as Reynolds has correctly IDed, their actual power positions given their actual goals are not actually numerically symettrical.

That gives Manchin real world leverage where Bernie does not. Not the simple willingness to use power.

Though all the incentives favor obstruction in order to placate the base, the loss of the Senate and WH in 2020 showed the base won‘t be enough to hold power. The Republicans are going to eventually have to DO something for the tribalist and country club Republicans or I can‘t see them continuing to vote GOP. They won‘t switch parties, but they could start to not participate if there‘s nothing in it for them. The scaremongering about radicals and socialists isn‘t going to convince any right-center folks in the midst of a strong economy that their way of life is at stake.

If Biden governs even half as competently as he has so far, the Republicans are going to have to adjust. Their problem is they have very few ideas to draw from and no good messengers.

Funny how nobody seems to remember the *proposed tax increases* to pay for at least part of these proposals. Everybody just uncritically buys into the Republican “deficit spending” framing the GOP puts forth every time* the DEMs try to do something.

*remember what the GOP said about the ACA?

**I have read of the DEM proposed tax increases, but have no idea how accurate it is.

Maybe it’s me, but I see a large difference between the following quotes from the original post:

“In the past, the opposition would have been able to force a lower price tag. But when the opposition is interested more in pleasing their base via rhetoric and when actual cooperation can get you in trouble with that base, the opposition actually takes itself out of the legislative game.”

and

“Put another way: if the Democrats have the votes to pass X legislation, what does it really benefit them to get less than X just so that they can say a few Republicans voted for it? If the bill passes, the bill passes. The number of opposition lawmakers who joined in passage does not make the bill more gooder.

A bill passed with zero opposition votes and one passed with all the opposition votes is the same thing: a law. And while people say they want bipartisan behavior in Congress, at the end of the day only nerds know (or care) the vote counts for passed legislation.”

The second quote describes a world where Republicans are interested in compromise and it is possible to pass a bill with some number of Republicans voting for it. If we were in that world, there would be large advantages for the Democrats to compromise — it makes it harder for Republicans to attack Democratic policies if some number of Republicans voted for them, and harder for Republicans to seek to repeal those policies when they are in control if it means some Republicans would have to vote to repeal a law they voted to pass.

However, since we are not in that world, but rather in the world described in the first quote, Democrats are forced to go it alone, and only those policies which all of the Democrats will vote for are those which will be enacted into law.

Manchin and Sinema are both Democrats, and we’re committed to given Biden a Covid rescue plan.

The question becomes whether we have a medium bill with Bernie and Warren trying to bolster it around the edges, or a stronger bill with our two most conservative senators trying to trim it.

If there were 5-10 actually gettable Republican votes, they would have had a seat at the table and it would have been the smaller, medium bill, with Bernie and Warren going to the mat for slightly larger support for local governments and losing (rather than winning there and fighting their losing battle on $15/hr)

Manchin wasn’t going to vote against covid relief. Not if his vote mattered. Manchin would go as small as he could get away with though, if he had some cover.

But, no Republicans, no cover.

Republicans would do well to get on board with a jobs/infrastructure plan to shape it more to their liking, if they care.

(I could see Hawley taking credit for holding back socialism…)

Joe Biden is 78 years old. He may well have decided to run again in ’24, meaning he would be closer to 90 than 80 if he won and served a full second term. He’s not a fool; indeed a propensity to under-estimate his intelligence has been typical of his media coverage for a long time. He knows there’s a good chance he won’t make it to 2029. Consequently he can concentrate exclusively on doing what he thinks is in the best interests of the nation, without worrying about its implications for his career after the presidency.

Why wouldn’t he go for broke?

A few weeks ago I made the point that if a doctor got a $10,000 raise every year, and his debt increased $5,000 every year, the doctor never had to change, and a couple of commenters utterly dismissed it.

I actually wasn’t going to read the Sullivan essay until I saw this. I was curious to see if, based on the economic part of the article, he would at least identify the most relevant racial politic issue to consider. He got close to it when he wrote “the first black president with a quintessentially conservative disposition” but then misses the boat entirely.

I think we need to look at racial reactions to Biden’s recovery effort and compare it to what happened in 2009 with Obama’s recovery effort. Perhaps this will change, but it’s striking so far to note that with a far larger and more progressive plan, we have yet to see a real reemergence of the “Tea Party” or a similar group.

Granted, it can be argued that they simply morphed into the Trump base. However, I think an equally valid hypothesis is that there is far less resistance to this type of plan (including seeing it as fundamentally “unAmerican”) because it is being advanced by a white President versus a Black one.

@OzarkHillbilly:

I haven’t forgotten the proposed tax increases. I also know that even if they increase taxes (which they should) we are still going to be running deficits, which is why I focused on that aspect it.

@Teve: But the micro effects on an individual and those on a nation are different. In the nation’s micro effects, the fact that you (as a low income, unsteadily employed person) are losing ground as very low inflation still successfully erodes your economic security while increasing the value of the holdings of the 0.1% doesn’t happen to the doctor in the example.

Indeed, one wonders if mentioning Sullivan’s article at all was really necessary for the points you wanted to make? He’s been really bad on race issues for a long time, and subsequent to being resigned from New York magazine, he’s basically given up even the pretense of hiding his views. Given he’s one of the people pushing “white replacement theory” lately, it seems this discussion would be much better off without driving traffic to an open white supremacist.