America’s “Family Secret” or Just Plain Denial?

Slavery is an inextricable part of our past, whether we want to talk about it or not.

Reuters has a new multi-party series called Slavery’s Descendants. Part I is entitled America’s Family Secret and it has the following description: “More than 100 U.S. leaders – lawmakers, presidents, governors and justices – have slaveholding ancestors, a Reuters examination found. Few are willing to talk about their ties to America’s ‘original sin.'”

To be honest, I was surprised that the number wasn’t higher (and I was not surprised that few wanted to talk about it). A main way to be exempt is to be, like Donald Trump, a person whose family migrated here after slavery was abolished. Of course, if your family was overwhelmingly from non-slave states or your ancestors were down the economic ladder, that would help as well. But considering that if one is in the elite now the odds are higher than some of your ancestors were elite as well, and given that there are more possibilities to find slaveowners as your family tree branch back in time, it is hardly surprising that a lot of our leaders have such histories.

After all, there were almost 4 million enslaved persons in the United States on the eve of the Civil War with a national population of around 31 million.

Here’s the basic breakdown:

- 100 members of Congress, 28 of whom are in the Senate. “They include some of the most influential politicians in America: Republican senators Mitch McConnell, Lindsey Graham, Tom Cotton and James Lankford, and Democrats Elizabeth Warren, Tammy Duckworth, Jeanne Shaheen and Maggie Hassan.”

- Every living president except Donald Trump.

- Justices Amy Coney Barrett and Neil Gorsuch.

- 11 of 50 governors. “They include eight chief executives of the 11 states that formed the Confederate States of America, which seceded and waged war to preserve slavery.”

Not surprisingly, South Carolina really stands out:

South Carolina, where the Civil War began, illustrates the familial ties between the American political elite and the nation’s history of slavery. Every member of the state’s nine-person delegation to the last Congress has an ancestral link. The state’s two Black members of Congress – Senator and Republican presidential candidate Tim Scott and Representative James Clyburn, a powerful Democrat – have forebears who were enslaved. Each of the seven white lawmakers who served in the 117th Congress is a direct descendant of a slaveholder, Reuters found. So too is the state’s Republican governor, Henry McMaster.

My second reaction was that it didn’t strike me as much of a “family secret” as much as that truth about our family that we know, but just don’t like to acknowledge. But, of course, the reality is that we do have a tendency to treat it that way, both personally and collectively. We really, really would prefer to think of it as something someone else did that has nothing to do with us.

To be clear: I am not asserting some notion of guilt-by-ancestral association. But, at a minimum, understanding how a given person got where they are in the now matters. It all illustrates that as much as we want to pretend like we are all self-made, this is simply not true in the main. Even if we build most of the structure, we cannot pretend like some of the foundations upon which we build were not laid by those who preceded us. Some acknowledgment and understanding of that fact is requisite.*

There is, clearly, no doubt whatsoever about the existence of slavery, but there is a huge amount of denial about its significance in building (quite literally) the country. The underlying animosity aimed at things like the 1619 Project, Critical Race Theory, and even affirmative action programs is rooted, is substantially rooted in the utter inability that we have as a country to truly accept the reality of our past and its deep, long-term implications.

This fact is well illustrated by the fact that the growing attempts to bring attention to the role of the enslaved in the building of America at historical sites* have created some level of backlash.

If, like me, you visited various sites in Washington, DC, or Virginia in the 1980s and 1990s and then did so in the 2010s and 2020s, you saw very different presentations of the slavery issue, for example. A great discussion of this can be found in Clint Smith’s book, How the Word is Passed in the chapter entitled “The Monticello Plantation.” Indeed, just calling it the “Monticello Plantation” is a useful reorientation to remind us all that it wasn’t just a cool house, but a working plantation run by slave labor. People often don’t want to be reminded of the “family secret” and would prefer just to look at the cool house.

I mean, who wants to be reminded of all that ugliness on vacation? Best to just have a whitewashed history lesson, right?**

Look, I am not saying that there are legitimate debates to be had and criticism to be levied at all of those topics. But, the reality is that a huge portion of the pushback is based on a real unwillingness to come to grips with the past.

I have read various discussions of backlash at the prominence of the slave issue at these sites (and I have a nagging memory of some discussion of it here at OTB at some point, but I cannot find it–not that I looked all that hard), but I cannot recall, apart from Smith’s book, a specific reference. So I went to Google Reviews and sorted from lowest rating and the very first one-star review that came up from a mere two months ago that reads as follows:

I was expecting a well thought out and informative tour of one of the greatest architectural triumph of the 18th century. Instead, I was treated with an obsessive overview of the lives of Thomas Jefferson‘s slaves and AA descendants. Not one mention of the Virginia Statute for religious freedom, which is arguably his most important contribution to American nation building.

I get that we can’t ignore slavers, but the visitor experience of this house went too far ignoring Jefferson’s accomplishments.

Don’t do my man TJ like this.

And yes, that is just one review (but it is still telling that I didn’t have to search very long at all to find one like this, as in mere seconds), and if you search the reviews on the term “slave” you find a number of additional reviews like the one above alongside others that praise the care taken on the subject.

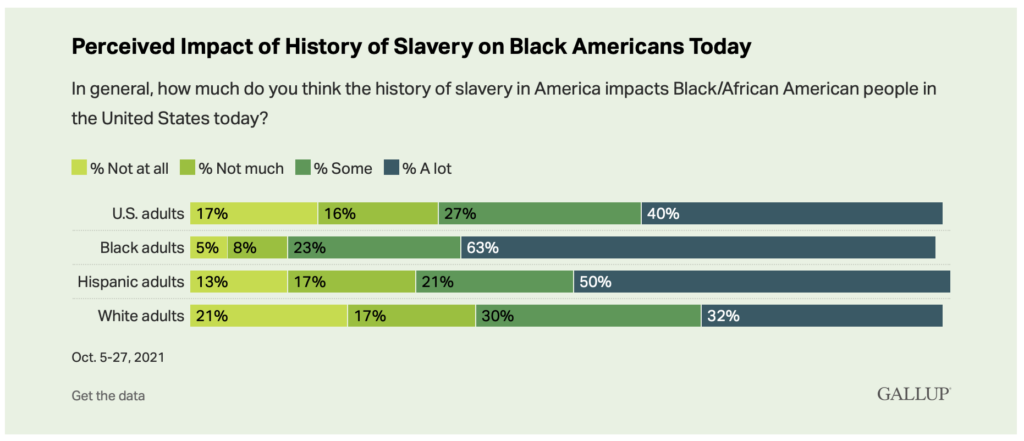

If we want to get more empirical and less anecdotal, we can turn to a Gallup poll from 2021, which shows that the majority of Americans believe that the federal government should address the issue:

As the U.S. marks the Juneteenth holiday commemorating the emancipation of U.S. slaves, a recent Gallup Center on Black Voices survey finds that most Americans believe Black people today have been affected by the history of slavery in the U.S. and that the federal government has a responsibility to address those effects. Americans who think the government is responsible generally believe all Black Americans, rather than just those descended from slaves, should benefit from programs to address the effects of slavery. But the public is divided on whether the federal government should formally apologize for slavery.

This is largely positive, but some of the specific numbers point out that while a majority holds these views, the minority that does is not small. The most telling is that only 32% of white adults in the survey think that slavery impacts Blacks “a lot” today versus 63% of Black adults. Now, in fairness, a majority (62%) of whites think slavery matters a combined “some” and “a lot”–but that still leave a large minority of whites who think that slavery had no impact, or “not much” and since whites make up the majority of the population, those views heavily affect the overall numbers.

Back to the Reuter’s piece, it was noted that a lot of the politicians identified did not want to comment for the piece, but one who did was Mo Brooks, a former US Representative from Alabama. But I note that his comments reflect both a common refrain that suggests a basic acknowledgment alongside some improper understandings of history.

One member of the 117th Congress with a slaveholding ancestor, former Representative Mo Brooks of Alabama, questioned what the country has to gain from revisiting the topic.

“Hopefully, everybody in America is smart enough to know that slavery is abhorrent,” Brooks, who lost a U.S. Senate bid last year, said in a phone interview. “So the question then becomes, if everybody already knows that it’s abhorrent, what more can you teach from that?”

I think this a fairly typical view, especially among more conservative persons: that yes, slavery was bad. We all know that so what else do you need to know?

Brooks also has what I think is an also typical view in some circles about both a gauzy view of what the practice was like alongside an assumption that the problem was dealt with a long time ago:

Note his attempt at trying to rationalize away the past:

In an interview, Brooks said he hadn’t known that his ancestor, great-great-great-grandfather Thomas Ferguson, was a slaveholder. The farmer held one person – a 7-year-old boy – in bondage in Haywood County, North Carolina, according to the 1860 slave schedule. Reuters could find no records that show what became of the child’s parents. Had they died? Or was the family separated, sold piecemeal to other slaveholders?

Brooks wondered whether there might be a happier story behind why the boy was listed on the schedule. “It is hard to envision what kind of labor a 7-year-old boy could do to offset the food, shelter, clothing costs of that 7-year-old boy. Which raises the issue of whether this ancestor had the boy in his possession in a traditional slavery sense, or was intending to set that boy free once he reached the age of majority,” Brooks said.

Manumission was “highly unusual,” said historian Marie Jenkins Schwartz, author of Born in Bondage: Growing Up Enslaved in the Antebellum South. “By the age of 7, an enslaved child would be expected to be productive,” potentially helping around the slaveholder’s house, watching their children, and learning agricultural or other adult jobs, she said. “They certainly didn’t have a life of leisure.”

Not only does his understanding of how enslaved children were treated need some serious work, but so too does his post-Civil War history:

Asked about his view on reparations, Brooks said the country has already paid one form of restitution, through a Civil War-era program proposed by Union General William Tecumseh Sherman.

“You may remember – what was it – 40 acres and a mule?” Brooks asked. “Now I’d have to check my history on how prevalent that was. But some freed slaves were given some amount of reparations, if my memory serves me correctly, and that is the origin of the phrase ‘40 acres and a mule.’

As Harvard’s Gates wrote, Sherman did issue a special order in 1865 calling for liberated families under his protection to be issued land and, later, a mule. The property in question was a strip of land down the country’s southeastern coast.

Had the order been followed, it would have provided Black Americans assets upon which to build new lives and perhaps pass wealth to subsequent generations.

But the program ended quickly, Gates wrote. President Andrew Johnson, the Southern sympathizer who succeeded Abraham Lincoln, “overturned the Order in the fall of 1865” and returned the land “to the very people who had declared war on the United States of America.”

The United States has never paid restitution for slavery.

Ironically, Brooks sponsored the “Saving American History Act” aimed at the 1619 Project.

“The Federal Government,” the bill reads, “has a strong interest in promoting an accurate account of the Nation’s history through public schools and forming young people into knowledgeable and patriotic citizens.”

“It’s always good to know history,” Brooks told Reuters.

Well, indeed.

Sigh.

The reason that CRT talks about structural racism and why terms like “white privilege” exist is to try and point out that the present was built on the past, both in terms of the physical spaces we occupy but also the existing social and political structures. And the past was one of chattel slavery in the United States until the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 (and really not until the 13th Amendment in 1865).

It is worth pointing out that the origin of Juneteenth as a celebration is that the news of the Emancipation Proclamation did not reach Texas until June 19, 1865, a full two and a half years after it was issued. This is s very minor, but also very real, example of how the legal does not automatically translate into the real. The history of promises unfulfilled (e.g., forty acres and a mule), or delayed in being fulfilled is a major part of the history of Blacks in the United States. It may be easy to glide over the two and a half years as just a historical fact, but don’t ignore that was two and half years of extra enslavement for somewhere near 200,000 human beings.

The next century is one of semi-slavery via sharecropping, using Black felons as labor, lynchings Jim Crow, the denial of the vote, and so forth. The Civil Rights Act is not signed into law until just shy of the 100th anniversary of the 13th Amendment.

And, it should be noted, that the push-back against CRT and, really, any teaching the highlights the actual history of the United States on topics of race and slavery (as opposed to a more heroic past narrative) is because many people don’t want to engage in the “family secret” of the nation as a whole.

All of this seems relevant as we continue to struggle with issues like voting rights (including basic access to the polls as well as issues like felon disenfranchisement). It is relevant as we decide that race-based affirmative action is not constitutional for college admissions. It seems relevant as we try to assess why the federal prison population is disproportionally Black or why the Black poverty rate is twice that of whites. It is relevant to the question of police violence against Blacks. It is even relevant to ongoing discussions about Civil War memorials.

To range into public policy, and without even getting too complicated, we could invest a lot more in education, both K-12 and post-secondary in a way that was targeted at the economically disadvantaged. We could spend more on infrastructure, especially in areas with heavy minority populations. On a grander scale, it would help if our system of representative democracy was better representative of the population, to include a fairer representation of urban areas and interests.

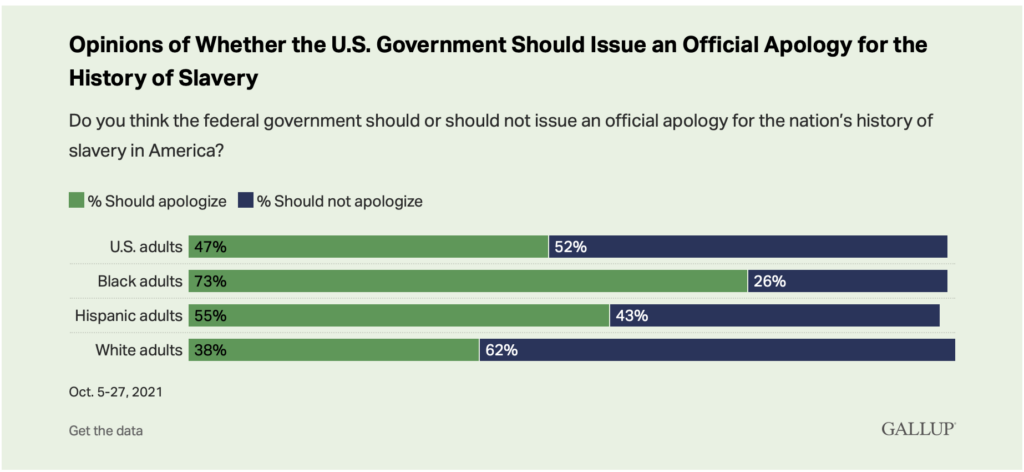

But it is telling that something as simple as a formal apology for slavery (back to the Gallup poll) is an issue that most Americans, and a large majority of white Americans, oppose:

It really does make you wonder why this would be something to oppose, unless, of course, we just don’t want to deal with the implications of the family secret.

On this issue, the Gallup write-up acknowledges:

In 2008, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a resolution that apologized for slavery, and the U.S. Senate adopted a different resolution in 2009. The two chambers have never passed a joint bill, so it is unclear whether those prior actions constitute an official government apology.

Oddly enough, I have no neat and tidy solution to these issues. I do think that we need much more honest acknowledgment of our past, even the uncomfortable parts. I would further note, for any who think otherwise, it is quite possible to love one’s country and be critical of its past and frustrated with its present. Indeed, true love requires embracing the whole package, not just some idealized version.

Since I am finishing this post on Independence Day, let me state that my personal goal has always been to treat Jefferson’s statement that “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.–That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed” should be our ongoing aspirational goal, one not yet perfected, but one that we collectively seek to perfect as the years pass.

*No doubt some readers are utter masters of their own fates, and the past had no influence over them whatsoever in either the micro or the macro. Indeed, they created their own genes and innate talents out of raw will to go along with their utter lack of any reliance on the physical realities that preceded them. To them we can only give a wide berth for the rest of us can only stand in awe.

**See also, The National Parks Conservation Association, ‘An Honest Reckoning.’

The emotional barriers to studying, researching and presenting the realities of slavery are also formidable. The subject is painful for many people, and those speaking candidly about this country’s history of racism and cruelty may be met with resistance. Over the summer, online reviews of plantations in the South went viral after visitors griped about having to hear about slavery. “Would not recommend … Tour was all about how hard it was for the slaves,” one reviewer wrote.

“Let’s begin with the fact that your discomfort dictates that these things are not discussed,” said Cheryl Janifer LaRoche, an assistant research professor at University of Maryland whose three-year ethnographic study of those enslaved at Hampton was scheduled to conclude in late 2019 (but may continue). “How do we get an honest reckoning of what went on at Hampton? Many people don’t even know there was slavery in Maryland.”

I think in a lot of cases it’s more that they’re smart enough to know that they’re supposed to say that slavery is abhorrent than it is that they actually know that it’s abhorrent.

Good, thoughtful piece, Steven. We like to talk about how much we love a redemption narrative. How hard would it be to say, “Yes, my ancestors owned slaves and were racist a-holes, but we’ve learned better.” (Full disclosure, mine appeared way after the Civil War, possibly wet backing into MN from Canada.) Unremarked in the quoted articles is the number of Blacks who have slaveholder ancestors, quite possibly including Clyburn and Scott, and how that usually came to be.

An excellent read for Independence Day.

Great piece. It fits in nicely into my big hobby of the last 2-3 years: family genealogy. About half my family tree came in from Canada and Scotland post 1865. I have Anabaptist ancestors from the early 1700s in NY and Pennsylvania and learned that the Mennonites renounced slavery in 1688. OTOH, my great grandfather was born in Jamaica in 1837 and soon returned to Scotland at age 2. What were his parents doing in Jamaica? Probably minor administrators/workers for the British empire. However, slavery wasn’t abolished in Jamaica until 1838 and they returned soon after that. Hmmm.

Really well-thought-out and written post Steven. I don’t think there is much to add to this other than bravo.

And given this day and the topic of this thread, a link to “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” by the always doing good things Frederick Douglas: https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/nations-story-what-slave-fourth-july

Yes, slavery was and is, evil. So is collective guilt. The historic guilt of Jews for supposedly being responsible for killing Christ – although, to be clear, it was a Roman – was a pretext for pogroms and expulsions and eventually, genocide. Peoples are not guilty. Populations are not guilty. Races are not guilty.

I don’t think reparations hold up as a moral choice. It might be a feel-good choice to expiate White guilt, but it is based on a very shaky notion of morality and responsibility.

As a political question I think national reparations to Blacks would be the end of Black political influence. The mood would be, ‘Well, that’s sorted, all debts paid, now whaddya still bitchin’ about?’ What’s funny is that Republicans don’t embrace it as it would shatter the political unity between White Democrats and Black Democrats.

Should we do everything possible to reduce and eventually erase the after-effects of slavery and Jim Crow? Obviously. Should that include reparations? Only if Blacks want to form their own political party, because it would be the end of any national sense of obligation to Blacks. It would finish off whatever is left of a Black-Brown alliance as Hispanics would have their own claims, as would certainly Native Americans (can we have the continent back?) and Asians. And hell, the Irish and the Jews. And the gays.

Good feels. Shaky morality. Bad politics.

But that all has nothing to do with teaching kids the truth in schools. I would offer a simple artifact I saw in the Smithsonian. A tiny pair of iron shackles designed for a child. Think of the creature who would place an order for such an object. Think of the blacksmith who would have forged them, very likely a slave himself. Think of the mother, the father, and imagine seeing your own child in shackles. This is moral atrocity, a monstrous evil, and if we could dig up and re-animate the people who did that I’d happily shoot them in the head.

We can’t do that. We also can’t dig Hitler up, or Stalin, or Mao, or Tsar Alexander, or Genghis or Attila. We need to find a way to cure society of the present evil of racism, and yes, the lingering oppression of institutionalized racism, but if we do it in the form of reparations it will be a mistake. It will not accomplish what advocates hope it will accomplish, and it will send the country racing rightward.

Well, you seem to skip over the slaves in Kentucky and Delaware that weren’t freed until December of 1865 when the 13th amendment was ratified. Six months after slaves in Galveston were informed they were free when the Union army took control less than 2 months after the Confederate surrender at Bennett Place. The war didn’t end at Appomattox, it ended a few weeks later when Sherman accepted Johnston’s surrender of the bulk of the Confederate forces, and subsequent fall of the Confederate government.

The Emancipation Proclamation did free slaves, but only those being held by the Union Army as enemy contraband. It relieved the Union army of the encumbrance of caring for those individuals (given the horrors of POW camps of the time) a good outcome. It permitted freed slaves to be inducted into the Union army to form additional fighting forces. It inhibited Britain and France from giving aid the Confederacy. But slaves were held in the United States for more than 6 months after every slave in the Confederate states were freed.

I would assert a notion of responsibility-by-ancestral-association.

If you’re in a position of power because of generational wealth and position created through slavery, you didn’t cause that, but you inherit the bad along with the good, and you have a moral obligation to use that power to help.

Even if you didn’t inherit wealth and position, but if you just benefited from the structural racism that is a legacy of slavery, you have a moral obligation to try to not support and reinforce that structural racism.

I’m not saying that one needs to take all their worldly goods and give them to the next Black person they see, but at the very least learn to recognize internal bias and try not to act on it.

“White privilege” is probably one of the worst terms that has ever been coined. The concept it describes is real, but … ugh. For far too many white folks the “privilege” is just having a softer sole on the boot on their neck, and the word “privilege” just gets them angry so they can’t hear anything after that. (Some wouldn’t listen anyway)

This only reinforces that we need less glossing over, but also a lot less slave porn history. A true accounting is clear enough.

But if we acknowledge Sherman’s assessment of slave treatment, is that glossing over? Slavery had economic foundations. It was waning until the cotton gin processing created a hot market for cotton in 1799. And a lot of the resistance to freeing slaves was due to the fear of what happened in what is now Haiti (1791-1804). I’ve not seen any writings on the peaceful manumission of slaves post-Confederacy. Did the Emancipation Proclamation create a defusing process?

Or perhaps Brooks’ ancestor was raping a 7 year old boy.

In all likelihood a 7 year old slave provided whatever value they did short term, but was also a long term investment. Slaves were pretty expensive.

I think Reconstruction is a bigger issue than slavery. Slavery was abolished, but Reconstruction put into place the use of governmental power to ensure the dominance of the White elites. The schools, the courts, sports, and even the religious practices came to freeze into place the place of African Americans. Yes, we are slowly unwinding these practices, but a lot of these institutional practices remain. How many Black football coaches are there in the SEC or the NFL? Those statues of CSA generals are reminders of these values.

@Michael Reynolds:

Who said anything about collective guilt?

Again, who said anything about races being guilty?

And, as you quickly pivot to, the “guilt” of the Jews was not the Jews feeling guilty, it was others assigning that guilt and then using that assignment as a weapon. What does that have to do with my post?

@Slugger:

Well, slavery was the use of governmental power to ensure the enslavement of Blacks. Reconstruction–or, more specifically, the incomplete, failed reconstruction of the CSA states was as much a continuation as the former enslavers could get away with.

Like many white people, my ancestors came over in the great waves of immigration in the 1880s and were given free land by the US government via the Homestead Act.

As a consequence, their children prospered, who then later sent sons to WWII, who in turn took advantage of the GI Bill and VA loans to move into the great postwar middle class, and send the next generation (me) to college, where I am now a comfortable white collar professional.

So when I hear whining about how unfair some form of reparations is, I wonder, why did my family deserve free land, low interest loans, and college grants?

The US government spent vast amounts of tax revenue to drive off the Native people from the land which they then handed out to peasants in the most wildly successful socialist redistribution schemes in history.

Tax money collected in part from the black sharecroppers. Did they grumble about how unfair it was that their tax money was being used to give free stuff to newly arrived white immigrants?

Family secret, good god, Americans can hardly ever stop licking at the old scar…

Other countries have rather more recent history of slavery, even century more recent, and spend rather less time talking about it.

There is something profoundly illiberal and unhealthy to present as some personal shame or sin if a relatively distant ancestor was either slave or slaveowner.

It is regardless rather more politically pragmatic and practical to point a finger to the much more recent crimes and sins of say the 20th century Jim Crow (of course itself having lines drawn back to slavery but rather less susceptible to the reaction of post-slavery immigrants that my family had no tie there).

The lack of support to an apology is not in the least bit puzzling nor surprising. One can simply look to european examples relative to crimes that have no slavery aspect – no national group likes and unless forced generally accepts such. If one is not being an over intellectualising intellectual this should not be surprising nor puzzling in the least – not a matter of defence but pure human nature.

Beni Adam, Beni Adam

(or one can look at the actual living memory experience of France and Algeria where no apology for well documented crimes will ever be made – at best the grudging semi apology to the poor harki bastards who fought for France)

As frankly such apologies solve nothing at all hardly worth spending political capital on achieving them.

@Steven L. Taylor:

I apologize if it bothers you, but I sometimes use your (or James’) posts to look at different angles of an issue. So I broadened out to reparations, an idea that relies on notions of collective guilt. I’m less interested generally in the right or wrong which tends to be obvious, and focus instead on politics and real world political impacts.

I am always 100% in favor of teaching the historical truth, regardless of the age group. Indeed, I’ve been doing it professionally for quite some time now. (I’d actually begun planning a trilogy of books that would have dealt directly with the Civil War and its aftermath, but in the current environment I can’t do that. I note that I did write and publish a 1500 page trilogy examining the history of WW2 with particular focus on racism and misogyny in that era.) If we start with the premise that slavery is a horror and that we should examine the reality unflinchingly, that leads inevitably to, so what? So what do we do about it? Which leads to a range of issues from book banning to college admissions to gerrymandering to reparations and more.

I’m not an academic, and while I am very interested in learning things, I’ll always look at, OK, what can we do? Sometimes there’s something we can do, sometimes there isn’t. But I have a bias in favor of action. I don’t just want to understand a problem, I want to know how to fix it. Sometimes I don’t know how to fix a thing, I only know how not to.

@JKB:

Kudos for including a quote from Sherman which does an excellent job of pointing out how barbaric chattel slavery was up until the Civil War and how easily such evil behavior was discussed in polite society.

Let’s take a look at the specific conditions from the quote:

First, let’s note that Sherman was not advocating for equal treatment. Just better, more humane treatment of… humans. So that’s not a great start.

So family separations were again the norm and transactions were based on the worst form of free market capitalism (i.e. who would pay the most for another human being at auction).

Cool… cool…

So again, even though slaves were considered property, there was a penalty of 1 year in prison for any owner that taught slaves to read. That’s before we get to what happened to the slaves who learned to read. Recorded punishments ranged from savage beatings to the amputation of fingers and toes.

BTW, I love the close of Sherman’s story:

Can you remind me how many of Sherman’s progressive as “correct” solutions were taken up by the Governor of Louisiana after that talk?

As far as I can tell Governor Moore, Sherman’s host, remained a staunch advocate for slavery which led the state to secede from the union. Here’s a summary of a speech he gave on December 10th, 1860 advocating for secession.

You can read the entire address here–it’s the first few pages. In it, Governor Moore makes it abundantly clear that he is advocating for Lousiana to leave the Union to preserve slavery–full stop. And to Sherman’s points above, that includes preserving the right to continue to separate families and enforcing brutal punishments to prevent human beings from learning to read amoung other things.

And all those folks attending the dinner who were so swayed in the moment by Sherman voted to secede in order to preserve slaery.

So, thanks again for illustrating how evil the treatment of fellow human beings was under Slavery just before the Civil War (not to mention how causally that was discussed by the great and powerful at the time). I appreciate how that gets back to the points Steven made in the article. Glad to see you are in agreement with us about these things.

I think that one thing that makes this discussion difficult is that slavery – the act of extracting unfree labor from other people – is not really the problem.

There were many historical injustices, but you don’t really hear the English clamor for reparations from Denmark for Lindisfarne. It’s what keeps happening that is the issue.

Thus, what is more like the real problem is that in Western societies unfree labor gradually became the exclusive domain of non-white people, Africans in particular. Looking specifically at North America, from the late 17th century onward white indentured servitude came to be increasingly replaced by black chattel slavery, to the extent that eventually petty much all unfree labor was black slave labor.

While whites became perceived as being too good for unfree labor (“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal…”), black people, because of their perceived inferiority, came to be identified as still suitable for enslavement, as lesser human beings.

Thus, black skin became a visible indicator of inferiority.

That racist heritage is still with us, in much the same way that outdated sexism is still with us today. The 19th Amendment ended neither sex-based inequality nor sex-based prejudice.

Like Simone de Beauvoir once wrote that “one is not born, but becomes a woman” (something still very true to this day), so (I would assume) “one is not born, but becomes black.”

Slavery did not just impact the enslaved, it also impacted the society of the enslavers. And parts of that society are still with us and continue to shape us (woman, man, black, white), whether we like it or not.

That is the real (because lasting) problem. People are, if only to some extent, still being treated according to outdated expectations and prejudices that society continues to impose upon us.

Relatedly, CRT is a way of talking not just about what happened, but also about what still happens. And that is exactly why it makes certain people so uncomfortable.

@mattbernius:

I’m not sure what you think history is, but your opinion of whether W.T. Sherman was anti-slavery or not is not informative. The passage was offered as a succinct assessment of slavery in the South just before the Civil War. It was an opinion offered at a dinner table as a guest, not some sophomores shouting down a speaker they’ve been told to hate.

You may be surprised that very few in the Civil War were advocating for equal treatment of slaves, only the end of slavery. Even the ideological zealots behind abolition, the “Damn Yankees” west of Boston, radical pietists, pushed the freeing of the slaves because it was believed that as slaves they were not free to have the emotional conversion to Christ.

To make this point. Here’s Gen. Sherman again, in a meeting as he awaited Gen Johnston’s reply to surrender terms.

I know, shocking that history is far messier than the narrative pushed by activists. But Republicans did keep most of the black vote until FDR.

@Gustopher:

Only some? And only of those whose privilege was limited to a softer boot on their neck (nice turn of phrase BTW! [thumbs up emoji])? It seems a lot of people that possess genuine white privilege–even some on these very comment threads (but that may be my cynicism–and white privilege–speaking) aren’t all that interested in hearing your words on this point.

@JKB:

And his words, as I demonstrate, show how awful and evil institution that broke apart families and brutally punished people who dared to teach people how to read or learn how to read. Or, if I’m getting that wrong, please let me know.

Or are you arguing those conditions weren’t that bad?

And to that point an institution that the dinner guests he lectured were willing to kill their fellow countrymen to preserve. To do that I cited the words of his host and provided you with a link to that address.

Strange, I’m not sure where I suggested history wasn’t messy. Further while I have limited training in historical methods, I cited other first-hand historical documents (including slave narratives) and primary sources to demonstrate how bad slavery was and how much the South fought to preserve it. You seem to keep relying on a single narrative… which checks notes… confirms exactly what I was saying.

Perhaps you can point me to how I’m getting history wrong?

Or are you suggesting that saying “slavery was actually ok” is good history? If so, perhaps you can cite some modern historians who would back that view up? You’ve already suggested that slavery was dying out, but if that was the case, why was the south and folks like Governor Moore so willing to go to war to defend that right

Huh, and what happened in the nearly 70 years since then? Glad to see you’re actually willing to entertain the great realignment of the parties in the mid-20th century and that impact on the Black vote. It’s almost like something happened around the 50’s and 50’s that changed things…

Hey let’s check the words of noted Black Republican Jackie Robinson:

Or does Robinson not count as a primary source on history like Sherman? If so why not?

@mattbernius: Nicely done! Kudos! (And, just for a moment, I will pause to note that your reply is a fine example of what I tried to remind JKB of yesterday in noting that it’s wise to think in terms of what your listeners heard as opposed to what you thought you said.)

Interesting piece Steven. A few thoughts.

I think Americans desperately want Slavery and ‘racism’ to be over.

Slavery existed from 1619 to 1865, but the Civil War solved that problem, right? Not so much. Thirteen years later, by 1878, Reconstruction wa ended and the subsequent roll back pushed us into a hard system of apartheid segregation and Jim Crow that lasted 86 years until the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Today I think that many Americans believe that, nearly 60 years after passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and 1965 Voting Rights Act, it’s time to cut the cord on programs intended to mitigate the effects of about 340 years of slavery and segregation. Certainly, with his 2013 Shelby decision, Justice Roberts indicated that the time and need for direct legal mitigation and vigilance was over, and he tried to deflect concern by saying that, if Congress feels otherwise they can legislate anew. To me it now feels like we’re in a time of a soft Reconstruction.

Slavery and the legacy of racism? We’ll get through these difficult times and come out as divided as we’ve always been.

@JKB:

BTW, what exactly is the narrative pushed by activists? I realized in retrospect that I honestly don’t know what you are referring to in this case.

Or wait, was it this?

If that’s the case I was well aware of that. It’s a pretty well-documented issue. Especially for those of us who know Frederick Douglas’s role (among others in that debate). Sharing the same adoptive city as Douglas, those discussions (especially in relation to the suffragette movement, and the deep divides it created between former allies, are fascinating and complex).

I’m also not sure where I suggested that I thought equal rights for freed-men was a done deal. Perhaps you can point that out to me. Also I’d love to understand why suggesting that *should have been the goal* following Douglas’s (amoung other’s arguements at the time) was such a bad thing?

Also, while I admit that I am disappointed by the fact that the abolitionist movement at the time wasn’t interchangeable with the quest for equal rights, I still think they are in a far better historic and moral position that the South and their decision to fight a war specifically over the preservation of Slavery.

Of course, if you’re feeling like making a “the Civil War was really about States Rights arguement” then I hope you’re enough of an armchair historian to go back to primary sources and answer the question of “State’s rights to primarily do what…?” If it helps, you can go back and look at the sources I linked above for that.

@JKB:

No, in fact, I don’t think many of us in this forum are surprised at all given that we all seem fairly familiar with the course of Reconstruction from emancipated to sharecropping and from citizenship to Jim Crow and the Klan.

CRT TRIGGER WARNING!!! STOP READING JK, YOU’VE BEEN WARNED!!!!!

I do also find it interesting that you have–perhaps inadvertently, perhaps by design–who can tell with you–that you have hit on an idea that is, in fact, a cornerstone of Critical Race Theory in noting that abolitionists had no particular plans in mind for what would happen as a result of emancipation. Well done–no matter what you intended!

ETA: Having read some, but not extensively on the antebellum pietist/abolitionists, I’d be interested in sources for your assertion “radical pietists, pushed the freeing of the slaves because it was believed that as slaves they were not free to have the emotional conversion to Christ.” I’ve not seen that point in my readings, but I may have missed it. In any event, I’m sure you’ll be able to find one source that will say that–and explain why “emotional conversion to Christ” was an issue–if you put your back to it.

@Michael Reynolds:

No, that does not bother me at all. It was just not clear that that was what you were doing. I tend to assume that commenters are directly commenting on the post unless they @ someone or explicitly state they are going on a tangent.

@al Ameda: I wouldn’t use the term “soft Reconstruction” for the period we’re entering. Maybe something like “re-JimCrowizing” but that seems cumbersome. Still, your conclusion is spot on–we will end up just as divided as we’ve always been, sorry to say.

ETA: A lyric came to mind just as I punched post: “Just keep on pushing hard, boy, try as you may, your going to wind up where you started from…

You’re going to wind up where you started from!

@mattbernius: I used to play tennis with a history prof who wrote a couple of books about the antebellum South. As I remember he made quite a point about the contrast between the Slave owners professions that Blacks were incapable of learning to read and the lengths they’d go to to make sure no traveling New England school marm ever got a chance to try to teach them.

@JKB:

Honest request: could you actually state, in a few direct sentences, what points you are trying to make?

Also: as others have noted, none of us thinks that the Civil War was about some idealized notion of utter equality for all.

@Michael Reynolds:

No, it doesn’t. At all. It relies on notions of victims who are still suffering the consequences of crimes against their ancestors and themselves.

It’s not about who was guilty; it’s about who was harmed, and what we can do to partially offset that.

If your ancestors have been on this continent long enough, you pretty much are guaranteed to have slave-owning ancestors. That’s a simple function of powers of 2 and how much regional migration happened. My immediate ancestors came from free states (Illinois and Indiana) but both of those were primarily settled from the South — Illinois from the lower Mississippi after the War of 1812, and Indiana from Kentucky after the Blackhawk Wars. My paternal line landed in Virginia in 1635 and migrated through North Carolina, Tennessee (where they were Andrew Jackson’s neighbors), and western Illinois before settling in central/eastern Illinois. More than a few slaves along the way.

My wife’s family has the distinction of featuring that remarkable breed, the slave-owning emancipationist. Seriously — people who owned slaves (in Kentucky) even while introducing bills to end slavery in the state and federal legislatures, and later serving in Republican cabinets after the Civil War. The one thing JKB gets almost right is that yes, it was complicated.

@DrDaveT:

Thanks for phrasing it that way. On this particular topic I have not seen that direct of a phrasing before and it really responses with me.

Well, you can start with Alex Haley’s “faction” (his word) ‘Roots’.

The move on the the “faction” of the 1619 project. They gloss over that none of the Africans who landed that year were slaves in North America. They were indentured servants as many whites were when they showed up on a ship and landed. That may hurt your modern sensibilities but it was 400 years ago. African’s enslaved them, sold them to Dutch slave traders, but once in Virginia they were indentured servants repaying the price of the supplies traded to the ship.

And the 1619 project ignores that the first black slave in Virginia was made a slave by Angolan Anthony Johnson (either landed in 1619 or thereabouts) who had worked off his indenture and developed a farm of his own. Where he had both African John Casor and several whites as indentured servants. When Casor claimed he had worked off his indenture, several times over, he left and was hired by Johnson’s white neighbor. Johnson sued the neighbor for the return of Casor asserting Casor was a lifelong slave, not an indentured servant. The court ruled Casor a slave and ordered his return and restitution paid to Johnson. Thus the first black slave in Virginia was the property of a black landowner.

Also, that there was widespread physical and sexual abuse of slaves. This happened, but was not as prolific as the slave porn purveyors promote. For no other reason than the entire society was focused on not provoking a slave revolt and having the slaughter that happened in what is now Haiti occur.

Accept the following fundamental fact about slavery, then the treatment of the slave whether kind or cruel doesn’t alter the evil of slavery.

@JKB:

First, can you point out where, in my citation of primary sources, I endorse Haley’s perspective?

Also, I find it telling that you keep citing really narrow specific cases in what appears to be an argument that “slavery really wasn’t that bad.” To which I ask, how is that minimization of the evils of slavery any less activist than “slavery porn.”

Also, I have to say phrases like:

Really doesn’t seem like the win you think it is. Especially given how you’ve maximized the violence in your characterization of things like the 2020 anti-police riots. Or is it wrong for people like me to critique your stance with “the majority of the protests weren’t violent?” Because that seems to be your argument about slavery: namely it wasn’t as bad as some people say.

So, I think we’re done here. Because I know where the rest of this conversation will go. For example, yes I know:

1. That Black African Tribes were involved in procuring slaves for the trade. No that doesn’t mean that Black folks or Africans have the same culpability as Europeans and Americans.

2. That some Black people in the South owned slaves. If you are minimizing slave physical and sexual abuse, then hopefully you would also acknowledge the number of these cases is staggeringly small relative to White Slave ownership.

3. That Black people fought on the side of the South during the Civil War. They did. Again, incredibly small numbers of them did and some of the accounts have since been called into question as fraud to get pensions.

Yes, history is complex. And yet, at the end of the day it isn’t. When it comes down to it, one of us is pointing out that owning other Humans was immoral and evil. And many people of that day believed that to be the case. And a part of our own country was so committed to the idea that that practice should continue that the went to war with the rest of the country over it. That’s something you have yet to attempt to contradict.

As far as I can tell, with all this history is complex bullshit you are throwing up, you appear to want to play the role of an apologist for slavery. To do that you are using an equally selective reading history as those you claim to attack.

All I say but “that’s a bold move cotton.” It also tells us far more about you than it does about anything else. And at the end of the day, I’m prepared to own that I’m firmly in the camp that Slavery was bad and a stain on our national history.

I wonder white that is so hard for you to join me on. Especially given how concern you are about government overreach and prosecution today… primarily of white people as far as I can tell. Because, again see your posts from the summer of 2020.

I am a bit of a genealogy nerd, and I traced my adoptive paternal line back to the mid 1600’s. My oldest adoptive paternal ancestor was a boy taken prisoner at the battle of Worchester with Cromwell’s New Model Army and shipped to Virginia on a prison ship, where he was an indentured servant for some period of time. Then the paternal line moved around and was in Mississippi before the Civil War, and the family’s men (my paternal ancestor and his brothers) at the time fought the Union in a Mississippi regiment. I don’t know if any were slaveholders, but it’s certainly a possibility.Very soon after the Civil War, my paternal line moved to Texas and then Colorado in the late 1800s. My grandfather was born in Denver at the turn of the century, his father was born in Texas and his father was in MS during the Civil War era.

Unfortunately, I ran into a dead end in the late 1800s with my maternal line and haven’t been able to progress further. But I traced her father back to 1720 and that ancestor was an Ulster Presbeterian, who fled the religious persecution going on at that time. He landed in South Carolina but quickly ended up in Kentucky where that line remained until my maternal grandfather came to Colorado around 1920, married, divorced, then married my grandmother and had my Mom. Then he murdered his boss and went to prison, leaving my grandmother to raise two daughters alone during the Depression.

Then, a couple of years ago, I found my birth mother. I haven’t done detailed research yet (it’s very time-consuming), but her line appears to be late 1800’s Norwegian immigrants. The birth father I have nothing on yet and no contact with him.

Anyway, I could spend a lot of words talking about what I’ve discovered so far, but will spare you all from that. So with that preamble, a few thoughts and questions.

Looking at their methodology, they appeared do what most geneologists do and focused on the direct maternal and paternal lines. But, of course, one’s ancestors are much, much more than that. Just looking at grandparents and great-grandparents, you can see the number depending on how far back you go. Most people alive today will have civil-war era ancestors at the 3-5th generation, so that’s a minimum of six and it quickly scales from there.

On the contrary, I would be surprised if most people knew these histories. The whole “family secret” headline is misleading IMO. I very much doubt the vast majority of people know much about their family history beyond great grandparents. It did take, after all, a team of well-resourced researchers over a year to uncover these histories. In my own case, I knew nothing until I spent the time (and money) to do the research myself – and I’m far from finished. Most people don’t do any research.

If you’re not asserting guilt-by-association, then what are you asserting? It’s not very clear. And understanding matters how, especially at 3+ generations? If a person, found out that part of their family line has a slaveholder several generations ago, what are they supposed to do or feel with that new information?

Or maybe people don’t think they should apologize for something they had nothing to do with? To be clear, I’m not against a formal apology, but it seems to me there are other explanations for why people would be skeptical of this other than a supposed lack of desire to deal with the implications.

What reality are we collectively supposed to accept that “we” are not accepting and what, exactly, do you think we need to do? IOW, is there a set of criteria that shows what acceptance looks like that can be evaluated?

@Andy:

It seems to me that the reality that many are not accepting is that pervasive systemic racism is the dominant (sole?) cause of black American underachievement and failure to prosper relative to other groups — including any dysfunctional or self-destructive features of Black American culture one cares to point at. The alternative explanation — that Blacks are just inherently inferior and incapable — does not stand up to close scrutiny.

What we need to do about it is try to not only end the systematic abuse, but make up for it as best we can. Not because we personally are guilty, but because it’s the just thing to do.

I find it incomprehensible that the same people who perfectly understand why it is just to restore artworks stolen from Jews by the Nazis to the families they were stolen from somehow don’t see the need to restore anything at all to the families robbed and stunted by Jim Crow and redlining and segregation, much less by slavery itself. It’s as if the scale and duration of the crime somehow makes it immune to ordinary ethical reasoning.

A couple of thoughts:

@DrDaveT:

But it does! There are real difficulties here. It’s far easier to return a stolen painting than to account for deeply-rooted social structures. In the latter case, did all victims suffer equally and how can you blame the perpetrators if they, too, were indoctrinated from a young age, brought up – regardless of their actual will – into a system that they didn’t pick?

In a similar vein, how would you actually go about introducing a system for reparations that would have men pay women for millennia of sexism?

I fear that reparations for such long-term, structural injustices are pretty much a dead end. Not least because these structural issues won’t disappear once the money is paid.

The only thing that you can realistically do, I think, is to try and make our current society more just and equitable. (Too bad that a corrupt SCOTUS disagrees.)

@Matt Bernius:

Why don’t Africans have the same culpability? (I’m not trying to argue that their culpability somehow diminishes ours, by the way.) Africans structurally fucked up their societies, too, by capturing and selling their neighbors to the highest bidder. The robbing part of the transatlantic slave trade was done by Africans themselves.

Don’t you think that this hadn’t had lasting consequences? Imagine living in a society where still-existing elite groups once got to where they are now by selling people like you to strange, slave-holding foreigners.

In that regard, Lounsbury’s comment is almost funny:

At least in some African countries, they don’t talk about it because it is close to being a taboo: a source of ongoing shame and, potentially, deep-seated social tensions.

I would argue that openly discussing these issues is a sign of societal health rather than weakness.

But if you want to have discussions like this, let’s not make Europeans and white Americans out as the only villains here. It’s not even necessary. What we (assuming you fall into one of these categories) did was bad enough as it is.

@Michael Reynolds:

HA! No, sir.

Reparations are not about anyone’s alleged guilt. Reparations are a (tried-and-true btw) economic remedy to persistent inequalities rooted in state-sanctioned violence and discrimination — about establishing justice and supporting the general welfare etc etc. Reparations are a policy proposal, not a punishment.

Yes it is difficult for some — fortunately not all — whites to wrap their heads around, understandably so, but not *everything* is about you lol

@drj:

I disagree — see below.

Oh, there are certainly practical difficulties — but that’s not the same as there being any ethical ambiguity. Right and wrong don’t change just because millions were wronged, and justice for the many ought to be the same as justice for the few.

Why do you (and Michael, and others) insist on making this be about blame? I don’t want or need to blame anyone* — I just want to right the wrongs as best we can at this point. It’s not about punishing the arsonist; it’s about rebuilding the house.

First, I would not have men (uniquely, specifically) pay for anything — it’s not about blame. I would have our society collectively undertake measures to undo what we can. Affirmative Action is precisely such a measure, which is why last week’s decision is such a giant step backwards.

If you’re talking about a one-time lump-sum payment to designated individuals deemed to have been harmed, then I certainly agree. If nothing else, the structural issues prevent such a payment from having the value it ought to have. Yes, that’s paternalistic of me, but I think also realistic — I have studied lottery winners in the past.

*For instance, I think that only the US Government has standing to apologize for slavery. It’s the only “person” involved who is still around and had some faint possibility of having acted otherwise back then.

@drj:

I think your parenthetical kinda gets to my point. To be clear, I didn’t say “no culpability.”

Here’s why I argue for less and different culpability:

The difference in the nature of the practice (tribal versus National). Europeans, and when that comes to the Transatlantic Slave Trade, we’re really talking about Portugal, Britain, France, the Netherlands, and Spain. Much of that trade was also a part of the Colonial projects. So in this sense (especially when you add in the United States’ role) was slavery as a “modern” national product and endeavor. It also created a giant economic market for the slave trade.

To put in really REALLY reductive terms: it’s similar to a discussion about the relative culpability of Purdue Pharma and the Stackler Family versus Oxy and fentanyl dealers* on the overall Opioid crisis.

Nation-states didn’t exist in the same way in Africa that they did in Europe at the time. So things were much more based along ethic lines. And there has never been any sort of unified “African” identity in the same way. So yes, ethnic slavery did exist in Africa prior to the transatlantic slave trade, but not at the scale of slave-taking that it would come to exist. And it wasn’t a consistent practice (i.e. some groups engaged in it, others did not) and was not as integrated into the different societies there as it was in Europe or the US (or Brazil for that matter).

Again, I think certain African tribes do hold culpability. Just not the same, or as great culpability, as Europeans (going back to Columbus) and the US.

Also for context, the reason that I brought that point up is a common strategy among people who tend to be apologists for Slavery to bring up African Slavers as a way to minimize the culpability of Europeans and folks in the US… kinda like “well the Africans were already taking these slaves and forcing them onto the poor US and European nations who didn’t want those slaves to got to waste” (like they were week-old produce).

I’m sure it has some. I would also question the degree of impact slave trading had on current-day power relations versus the far larger issues of colonialism in Africa and the way that completely screwed up power relations (again, the two are very much linked). That said, I’m not an Africanist, so my ability to comment on these topics beyond what I wrote above is definitely limited.

—

* – As I said, this is a really simplistic reading. I understand that some of the African Slave Traders were much more like a cartel than a street level dealer. All models are wrong, some are useful.

@Andy: First, if the past really doesn’t matter, why were so few of the people identified in the piece willing to talk about it?

Second, why are we, as a society, often only willing to go as far as Brooks does, i.e., “slavery bad” and that’s it?

Third, the fact that we, as a country, still argue over whether the Civil War was over slavery or “states’ rights” or tariffs or whatever underscores a lack of consensus on the topic (as do all of those battle flags, among other things).

Fourth, what is the accepted narrative (conscious or not) about why Blacks are more in poverty, more in prison, etc? Is it because of the consequences of centuries of enslavement and then post-enslavement policies or because, well, you know, those people aren’t smart, are lazy, are violent, etc?

Fifth, a lot of public policy wants to just say “Well, that’s all the past, so let’s just all start off as equals now.” That stance ignores the fourth point.

@DrDaveT:

This.

@DrDaveT:

At the barest of minimums, a formal acknowledge and apology by the US government (not half-baked dueling resolutions from the two chambers) is necessary in my view. The fact that we have not, and seem incapable of it, underscores my overall point, I would argue.

@DrDaveT:

Thanks, that is a good comprehensive answer I need to mull over more thoroughly.

Just one thought on this:

Do you really think those are the only two explanations? All problems in the African-American community can be distilled into competing, single-cause narratives? I do think the legacy of slavery is a big factor, but I don’t agree with this either/or framing.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Why indeed? Is your theory the only possible one?

How much further do you think “society” should go? Please be specific.

My view is that these are not mutually exclusive. The Civil War was definitely about slavery, which is the context that underlies the entire conflict, and it’s also true that it was also about the political question of whether states could leave the Union. And yes, it even included “states rights” – namely the question of whether states had the right to continue slavery either in the Union or outside of it.

Similar to my response to Dave, do you actually believe there are only two mutually-exclusive explanations for why black people in America are more in poverty?

I also reject the subtext of that framing – that anyone who doesn’t agree with you that slavery is the sole cause of contemporary problems in the black community must therefore believe that black people are stupid and lazy.

Quite the contrary, public policy to combat persistent poverty is inherently difficult. The notion that the actions we should take to alleviate it will become clear and effective if only we admit to ourselves some greater level of historical acknowledgment about slavery and its legacy – which you’ve yet to define – is a dubious proposition IMO.

Again, I’m not at all opposed to this, but what would it actually accomplish in the lives of actual people?

@Matt Bernius:

I think this is inaccurate. Unfree labor in various forms was common throughout Africa. This also included chattel slavery.

By contrast, Europeans had to go to somewhere else get unfree labor precisely because it was no longer a part of their own societies. Of course, these same Europeans then created (color-based) slave societies in the New World. But this extra step would have been unnecessary if unfree labor had already been a widely accepted part of their existing societies.

As to the question where slavery was most integrated, I would argue that it is the place where you could kidnap your neighbors off the street or where you could come up with bogus witchcraft accusations in order to sell your fellow villagers to a local slave trader.

Moreover, I would say that this is arguably worse than buying some already enslaved strangers at a faraway coast.

Sure, Europeans created a very, very significant part of the demand for African slave labor, but at the time that the transatlantic slave trade was still a thing, almost all the power rested with the sellers. It should be noted that European colonization of Africa’s slave coasts only took off in the 1880s. I think this last observation also undermines to a significant degree your observation regarding nation states versus ethnic or tribal communities.

The sellers were always in a position to refuse – although this is, admittedly, complicated by the fact that the influx of wealth generated by the slave trade upset local balances of power. Local rulers who didn’t participate ran the risk of becoming weaker in relation to their peers who did.

A comparison: to whom do we assign the primary blame for the destabilization of large parts of Mexico? The local cartels or American narcotics consumers?

In a way, this is an apt comparison, I think: relatively poor society gets hopelessly corrupted by economic demand from much wealthier societies next to it.

You can’t just hand-wave away the actions of the cartels, even if the source of the problem ultimately lies somewhere else.

I mean, it’s fine if you still want to think that European culpability for the transatlantic slave trade is significantly bigger than the African culpability. I don’t really have a very strong opinion either way.

I just don’t think that it should be an automatic assumption, because it does contribute to overly simplistic assertions like “white bad, black good” – and that only provides ammunition to fools like JKB.

(And, again, African culpability does neither diminish ours, nor our obligation to remedy past behavior as best as we can.)

@DrDaveT:

It’s not the millions, it’s the passage of time that is the complicating factor.

Regardless, I do agree with you that there should be certain obligations – although not so much because of the past, but rather because of the ongoing impact of the past.

@Andy:

I think you are eliding the issue by suggesting we are over-simplifying.

I will say that the most important variable that explains the variation between the white and Black populations in the US is as I have described. But, yes, any social phenomenon is complex.

@Andy:

In this particular case, after much thought, yes — I do.

Black culture in America evolved as a response to and a coping mechanism for intense oppression over centuries. White America created the environment and constrained the responses. The result is their responsibility. Any other position requires you to blame black America for not managing to deal even better with their horrific treatment than they actually did. Blaming the victim is pretty much always wrong.

I do not disagree with people like John McWhorter who feel that black America needs to take charge of its own destiny and fix itself. That’s a positive and productive position for a black man to take. But it doesn’t change how we got here.

@drj:

Only for the policy response. The ethical analysis is quite straightforward, and independent of time.

(And even the policy problem is less challenging than the analogous ethical situation with respect to Native Americans…)

@Andy: @DrDaveT‘s response does make me wonder what other over-arching hypotheses you would suggest. If the over-arching explanation for Black development isn’t about past conditions, or about something inherent to the population, what are you suggesting should be included that isn’t?

@drj:

Thanks for sharing those details. I feel like your understanding of that part of the trade is deeper than mine, so I’ll stop commenting outside of my knowledge zone.

I think we’re ultimately in agreement about most of the major points (i.e. it’s a different sort of culpability and their culpability doesn’t negate the culpability of others).

Thanks for pushing me on this point.

@DrDaveT:

Because they’re making this about them personally.

@Andy:

Be careful with your paraphrases. First, it wasn’t just slavery, though that established the basic environment — the systemic oppression continued in various forms for the next 160 years after “emancipation” too. If it hadn’t, we might not be having this conversation. Second, “stupid and lazy” was not my phrasing, and only part of Steven’s. Are blacks inherently more violent than whites (or browns or Asians)? Less law-abiding? If not inherently, then what might explain the higher rates of violence and crime in black communities? Which of those factors are not either caused by or a response to oppression?

Like Steven, I would like to hear what third category of causal factors you think there might be that is neither innate nor a consequence of that particular series of environments.

@Andy:

But the contrarions have “yet to define” these other alleged causes that supposedly cannot be traced back — directly or indirectly — to the legacy of slavery, Jim Crown, and related systemic discrimination. Thus leaving their interlocutors free to offer subtext to fill in that gap.

Reflexive disagreement is easier than affirmative proposition.

@Matt Bernius:

Tribal versus national is false and oddly repeating an old racist framing on African history.

West and Central Africa were not mere Tribal geographies, but from before the European explorers hit the coasts, were home to proper state organised kingdoms and in fact even Empires quite worthy of Alexandre the Great, not mere tribes, Kingdoms (Angola, the Sahelian states, Benin etc). The Portuguese illustratively initially treated with the Angolan Kingdom as a perfectly reasonable late medieval peer. That did change later of course…

Organised state level human chattel trade pre-existed European entry (which is not to say the introduction of arms trade as the Europeans refined guns did not have some very nasty effects that it is quite reasonable to say were grotesquelly transformative).

Writing Tribal versus National is to repeat a fallacious racial trope.

Now back to the regularly scheduled ahistorical American navel gazing and scratching at old scars.

@DK:

This is just lazy. It’s fine to judge me, if you must, but at least put some serious effort into it.

I was reacting to an analogy of stolen artworks that attempted to explain how self-evidently easy it all was. You know, an analogy with perpetrators, victims, and thus – naturally – blame.

My point was that blame isn’t a useful concept when one wants to address multi-generational harm. And that, therefore, the clear and simple analogy wasn’t so applicable as one might hope.

But hey, don’t let my actual words stand in the way of scoring an easy point.

@drj:

This response surprises me, because part of the (intended) point of my analogy was that in fact we generally do NOT know who to blame for those crimes, and even if we did they’re all dead now and beyond punishment. The point of the effort is (yet again) not blame, but redress — getting the art back to the people it belongs to. Which we can sometimes do even in cases where we can’t pinpoint who the perps were any more precisely than “Germans, or maybe Italians.”

@DrDaveT:

My original point in this thread was that there should be redress not for the historical crime but for its ongoing consequences.

Mostly because you simply can’t (IMO) repair injustices that occurred more than a generation or two in the past. Moreover, the original injustice isn’t even the injustice that needs redressing in the present.

So let’s not focus on what happened then, but on what happens now as a direct result of what happened then.

You can return a stolen piece of art after more than half a century, but you can’t undo the long-term consequences of slavery (ongoing segregation, discrimination) by addressing the past horrors of slavery itself.

@JKB: The gist of your remark about Delaware and Kentucky is that both North and South are implicated in slaveholding and I agree with that. Even though the avowed purpose of secession was to preserve the institution of slavery.

It touched everyone in the US and has lingering effects even to our day. There is one branch of my family tree from MO and there was very likely slaveholding in that branch. Other branches come to this country in 1850ish and settled in the Dakotas, so no slaveholding there.

I have talked with some folks from South Carolina who were overall very nice, and enjoyable companions at a cruise dinner table. They appeared to carry some sort of guilt about the history of SC or maybe it was defiance. I wanted to tell them that what happened was bad, but it wasn’t them. Only what’s in their sphere imputes to them. But that seemed a bit personal.

I’ve lived in the South, I know quite a few people from the south. White people in the South, as a category, bear no more and no less responsibility for racial issues than white people in the rest of the country. And I also feel we (white people) need to move forward with less guilt and more resolve to make things better for everyone.

@drj:

Then we (almost) agree about that — but why keep bringing up blame, in that case?

I find the phrase “repair injustices” problematic — it isn’t the injustice that needs to be repaired, it’s the harm. (The system that is generating injustices needs to be fixed, too, but that’s a separate matter that I think we all agree on.) Redress is for the injuries done. The fact that the injuries were unjust is part of why redress is appropriate, but it isn’t the injustice per se that needs to be compensated for, unless one wishes to argue for a “pain and suffering” award beyond the actual harm incurred. That’s not insane — our legal system has long recognized that this is sometimes appropriate — but it’s not what I was thinking of.

That said, you are absolutely right that it is not generally possible to repair harm. If I break your Ming vase, there’s nothing anyone can do to fix that, to make it as if it had never happened. That doesn’t depend on how long ago it happened; it’s just a fact about harm. That doesn’t mean that you should get no compensation or redress for your broken vase, just because I can’t set time back and undo the damage perfectly.

Time and generations do make it harder to assess harm at the individual level; that’s one reason I prefer systemic policy redress (like affirmative action) over attempts to compensate individuals.

See above regarding injustice vs. harm — but it isn’t an either/or. The sum of the harms is what needs to be redressed, not any one particular harm. Huge harms 200 years ago, large harms 100 years ago, many small harms 50 years ago… they all add up, and sometimes compound. It’s the history as a whole that calls for redress, not any one moment or act or institution. Or so it seems to me.

@DrDaveT:

Personally, I don’t really care about blame. It’s how I read your comment, I guess. This phrase in particular:

In order to restore, I would say there has to be a pretty direct relation to a distinct, original crime. And that automatically gets you to perpetrators and blame.

Perhaps the word “repair” would have been more fitting there. Or perhaps my reading of your analogy was simply too narrow.

@DrDaveT:

Well, this is an interesting comment on multiple levels.

You point specifically to black culture as a factor, and note that it is a culture that developed because of historic oppression. Are you suggesting that black culture is holding black people back? And that white people are solely responsible for black culture – or at least any negative aspects of black culture? I think I’m probably missing something because I’m surprised that you’d make that argument. It sounds like a variation of what Moniyhan researched starting back in the mid-1960s and continued to focus on during his time in the Senate – a view that has – at least – fallen out of fashion.

Secondly, whether or not white people are responsible for black culture, the reality is that black culture, if it’s actually a problem, is a problem that white people cannot fix.

Third, not everything is about blame. Some things just are realities. For example, the fact that most black people in America today are born to single mothers (~70%) is not about blame. The sad reality is that single motherhood highly correlates with poverty and various other negative outcomes. The supposed need to find blame for that avoids the more important questions, like e why it is happening and even more important, what to do about it.

Also, that statistic has increased from around 25% in the 1960’s, to ~70% today, an almost three-fold increase. What explains that change?

This is one example of why I’m skeptical of a unified theory that slavery and systemic racism are to blame for everything that is wrong in the black community because it’s not clear what mechanism would cause the collapse of the black family after the Civil Rights movement.

More importantly, it’s not clear what “white” people individually or collectively are supposed to do to change that.

@Andy: @Andy:

Certainly black commenters like John McWhorter (Losing the Race) would say so. I have less standing than he does do opine on that.

Who else could be? Go back and read my previous post again — are you going to blame the victim, or blame the perp? If I torture you, who is responsible for your quirks afterward?

Probably true, but irrelevant to the question of redress. America as a whole can’t fix black culture, but they can certainly make amends for past harm.

I begin to doubt whether you’ve actually read anything I wrote up above.

I’m the one who has been saying, repeatedly, ad nauseum, that nothing is about blame. If you missed that, you probably missed everything else I’ve been saying. Try again. Then you can come back with a different theory of why nobody owes anyone anything. I can’t wait.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Well, that is a very different formulation from the stark binary which I objected to:

And the “aren’t smart, are lazy, are violent” is further rolled back to “something inherent in the population.”:

If your position the more recent formulation that it’s “the most important variable” then I largely agree with that, possibly with some caveats – namely how far you can iterate on that over time.

The other variables, IMO, aren’t a static over-arching set, but depend on and are differentiated by the specific problem you want to talk about.

And yes, social phenomenon is complex – I definitely agree with that and would add that most complex problems are multifactorial.

But this whole debate is, IMO, a side show because believing that, for example, the rise of unwed births since the 1960’s, or inner city crime and gangs in black neighborhoods, or the poverty gap, or everything bad is the result of centuries of racism doesn’t tell us how to solve or address that problem.